medieval manuscripts HT 2017

Mostly music and medicine

a selection of medieval manuscript codices

at Balliol College, Oxford

January-February 2017

Handlist of mss on display

MS 383. A particularly exquisitely written and illuminated 15th century copy of the French translation by Octovien de Saint Gelais, of Ovid’s Heroides. Open at ff. 84v-85r. The tenuous connection with medicine is that the grim and tragic stories of the Heroides have been cited as part of the literary tradition of ‘grief as medicine for grief’. The even more tenuous connection with music is the theory that Ovid may have intended the Heroides to be sung! Bequeathed by Richard Prosser, Fellow of the College, 1839. images online

MS 396. Five leaves of an early 14th century Sarum breviary, with musical notation, written in two columns of 28 lines with large red and blue flourished capitals. The leaves had been used as binder’s waste (endleaves etc) for a college account book, and were removed from its binding in 1898. They show considerable wear (from their post-liturgical existence) and chemical damage from glues. The current fascicule binding is modern. images online

MS 2. Late 13th century Bible, with very fine illuminated and historiated initials throughout, first Italian and later French. Open at ff.3v-4r, showing the Seven Days of Creation, accompanied by magnified prints. There is no definite information about how or when this book came to Balliol, but ownership inscriptions seem to indicate it must have been later than the 17th century. images online

MS 283. 13th century copy of Etymologies by Isidore of Seville. Medieval encyclopedias were attempts to encompass the whole of classical and contemporary thought and learning on all subjects; this one, written in Spain in the early part of the 7th century, was one of the most popular western medieval texts. Open at ff.50v-51r, showing entries on Medicine. Gift of William Gray, Bishop of Ely (d.1478). images online

MS 192. An early-15th century copy of the Quodlibeta of Duns Scotus as abbreviated by John Scharpe, and Robert Cowton’s Commentary on the Sentences (of Peter Lombard) as abbreviated by Richard Snettisham. Both of the main authors were Franciscans, theological heavyweights and contemporaries, or near-contemporaries, in Oxford in the late 14th century – their writings participated in and in their turn became part of a long tradition of theological verbal and written debate. No particular connection with medicine or music, but representative of the heavily theological content of the college’s medieval library. Open at ff. 66v-67r, part of a list of contents between the two main texts. The upper right of 67r shows several distinct cat paw prints – a recent news story about similar prints in a medieval manuscript got into the National Geographic and Smithsonian magazines, demonstrating the widening field of medieval codicology. Cats often feature in manuscript illuminations and scribal marginal doodles. Gift of Thomas Gascoigne (1404-1458, theologian and Chancellor of the University of Oxford), 1448. images online

MS 317. A mid-12th century copy of Boethius’ De institutione musica, an influential summary of ancient Greek musical theory and a key text in the medieval quadrivium (secondary study: arithmetic, geometry, music, astronomy). Boethius emphasises the relationship between mathematics and music, and discusses the importance of music – a powerful influence with potential for good or bad – not only in society but upon the mind and body of the individual. Open at ff.53v-54r, showing one of numerous diagrams of the divisions of the scale, with names of the intervals. Gift of Peter of Cossington, before 1276. images online

MS 250. A 13th or 14th century copy of several texts by Aristotle, written in Greek and widely read in Latin in the western Middle Ages, in the fields of philosophy (Rhetoric) and natural history (On the Movement of Animals, Problems, and the first book of History of Animals). Open at ff.41v-42r, showing the beginning of De Problematibus; the first section consists of medical problems, outlined in a list of contents. The illuminated initial is a good example; accompanying images show the scribal or later penwork decorations, chiefly of rather engaging birds and clusters of leaves and grapes. Provenance unknown; C14 College inventory mark. images online

MS 173A. Two texts bound together, one from the late 13th century (ff.1-73) and the other from the early 12th century (ff.74-119), both collections of short texts, 16 in all, of medieval music theory. Authors include Avicenna, Isidore of Seville, Odo of Cluny and others. This manuscript also includes the text, with diagrams, of Guido d‘Arezzo’s famous treatise on music (De Musica) – though the well-known ‘Guidonian hand’ diagram does not feature in this particular copy. Open at ff.75v-76r, showing coloured illustrations of musical instruments in a letter attributed to St Jerome ‘de generibus musicorum’ (On the kinds of music) – the text explains the theological symbolism of musical instruments in the Bible. Apparently part of William Gray’s mid-C15 gift. images online

MS 367. An 11th century copy, rebound in the 19th or 20th century, of an anonymous Antidotarium or book of remedies. Mostly of the later medieval (C13-14, Italian hands, in Latin) marginal notes add to the medical context of the main text, but one is a pen-trial (for testing a new quill) reading ‘Exurgens kaurum duc zephyr flatibus equor’. This phrase is a pangram or holoalphabetic sentence, i.e. containing all the letters of the (Latin) alphabet. Open at ff.7v-8r; one figure uses a brush to paint ointment on the arm of the other, illustrating the first paragraph, which describes the use of salve against cancre. This manuscript, though one of the oldest at Balliol, is one of the most recently acquired of the college’s medieval books; it was given by Sir John Conroy, comptroller to the Duchess of Kent (mother of Queen Victoria), probably ca 1900. images online

MS 231. A late 13th century copy of more than twenty texts on medicine by Galen, as translated into Latin from the original Greek – via Arabic. The handwriting is typical of university (rather than monastic) scriptoria of the period, possibly from Paris, but it is difficult to be certain, as books, scholars, scribes and styles moved back and forth across the Channel. Open at ff.1v-2r, showing later ownership and contents notes on the left and the beginning of the text on the right. The motif of a dog chasing a rabbit or hare, seen here decorating the bas-de-page on f.2r, is a common one in medieval manuscript illumination and does not relate directly to the text; otherwise this copy is not illustrated. The text on 1v provides unusual amounts of provenance information for this manuscript: Stephen of Cornwall, Master of Balliol ca. 1307, gave it to Simon Holbeche, who first studied at Balliol and continued his medical studies at Cambridge, becoming a Fellow of Peterhouse. Holbeche bequeathed it to Balliol in 1334/5, enjoining the Master and Scholars to pray for the soul of their former Master, Stephen of Cornwall. images online

MS 329. A 15th century copy of four texts in Middle English: two lists of herbal remedies; a translation in verse by John Lydgate of Aristotle’s (attr.) Secretum Secretorum, under the Latin title of De regimine principum (Advice to princes); and Lydgate’s own The Fall of Princes. Open at ff.15-16r, giving the Latin and English names and medicinal uses of plants, including Herb-Robert, mortagon (turk’s cap lily), woodruff, henbane and hyssop. Bequeathed by Dr George Coningesby, 1766. images online

MS 225. A 15th century collection of texts by and relating to St Birgitta (Bridget) of Sweden and her monastery at Wastena (Vadstena); the section detailing the Hours for her feast also provides liturgical music. Mynors dates this book to the early 15th century – near the time of the foundation of England’s only medieval Bridgettine monastery, Syon Abbey at Sheen. Open at ff. 206v-207r, showing text and musical notation for the beginning of the services for the Hours on the feast of St Birgitta (23 July – ‘celebratur in crastino marie magdalene,’ ‘to be celebrated on the day following the feast of Mary Magdalen [22 July]). This copy is much-annotated by Thomas Gascoigne, a prolific 15th century book collector and benefactor across the colleges and University; it is not clearly marked as his gift to the college, but the college inscription on what is now f.223v is late medieval rather than early modern. images online

MS 285. 13th century compendium of medical and religious texts by authors including Pseudo-Aristotle, Razes, and Ricardus Anglicus on medieval urinalysis. The volume is displayed open at a diagram of the hand, here used to illustrate a treatise in Anglo-Norman French, by the prolific Anon., on the principles of chiromancy or palmistry. The hand diagram was adapted by Guido of Arezzo for use in his famous treatise on music, and was widely used in the Middle Ages as a mnemonic device not only for teaching sight-singing, but also for outlining sermons, remembering prayers, and, of course counting. Gift of William Reed (d.1385; Bishop of Chichester, University benefactor, owner of ‘probably the largest private library in 14th-century England.’ images online

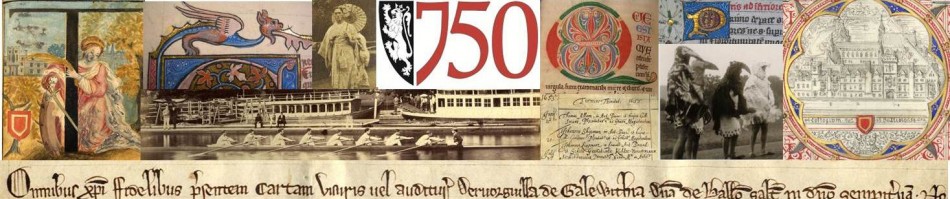

Additional: College Foundation Statutes (1282) and medieval seal matrices; Charter of Incorporation, 1588. images online

Things to think about:

These manuscripts are deliberately not displayed in a specific order, and the historic order of their college manuscript numbers does not reflect a hierarchy of age, size or subject. How do they relate to each other – by age, provenance, contents, style, users? How might you choose to group them, and why?

How do the illustrations in these manuscripts relate to the texts they accompany?

What are the functions of decorated initials?

How have musical and medical theories changed since these texts were required reading in universities? Has anything remained from the medieval curriculum?

Why would later benefactors continue to give medieval manuscript books to the college?

Why are there so few liturgical books in college collections, and why are they usually later gifts?

How have the functions of these books changed since they were written? Since they were first used in the college?

What kinds of information can digital images and other forms of surrogates and facsimiles, such as the magnified prints on display, provide about manuscripts that is difficult or impossible to derive from the original? What kinds of information can only be understood through direct examination of the original manuscript?

Did you know?

Many other medieval and early modern manuscript books from Balliol’s collection have been photographed, in part or in full, in response to researchers’ requests, and the digital images are available online via https://www.flickr.com/photos/balliolarchivist/collections/72157625091983501/ (or just search for ‘balliol manuscripts flickr’)

RAB Mynors published a catalogue of the first 450 manuscripts (all that were then in the College’s possession; there are now more than 470). The catalogue also includes a history of the college’s medieval library, with particular attention to the large donation of manuscript books (and one surviving printed book) by William Gray, Bishop of Ely. The catalogue, with links to images and citations for additional bibliography wherever possible, is online at http://archives.balliol.ox.ac.uk/Ancient%20MSS/ancientmss.asp

Visiting the exhibition:

Place: Balliol College Historic Collections Centre, St Cross Church Holywell, Manor Road, Oxford OX1 3UH – across the road from the English & Law faculty building. directions

Admission: public, free

Opening times: most weekday afternoons 2.30-5pm, 24 January – 16 February 2017, other times by appointment

N.B. Classes, group visits, research bookings and other events will continue at St Cross as usual during the period of the exhibition, and may be booked at short notice, so it’s advisable to check by email in advance if you want to come at a particular time – or just drop in whenever the OPEN sign is on the door!

Can’t make it in person? follow the links above to images of most of the manuscripts online, and click here for photos of the exhibition in situ.

Pingback: Mostly Music and Medicine – display | Balliol College Archives & Manuscripts