#mss2017 Introduction

Introduction

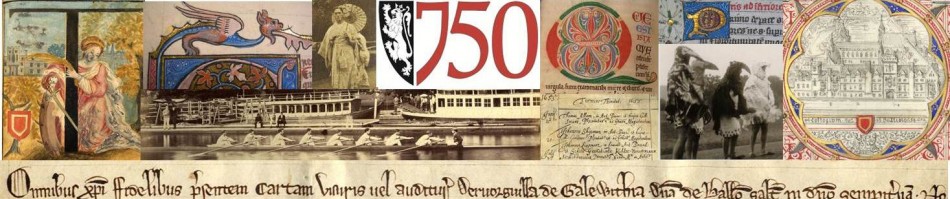

I have produced numerous small displays of medieval manuscripts for teaching and college events since I became responsible for the collection and moved it to the new premises in 2010-11, but this is the first major exhibition of Balliol’s western medieval manuscripts in the Historic Collections Centre at St Cross Church. It may even be the first exhibition of this collection that has been open to the public.

Because it’s rare for these ancient, unique and delicate objects to be exhibited, even to members of the College, I wanted to show as large a selection as possible, and to provide a broad overview of the collection. I have included manuscripts from the whole medieval period covered by Balliol’s collection (C11-16), representing a range of provenances, decoration and handwriting styles, contents, sizes, formats, physical condition, and conservation issues. Exceptions prove the rule; not everything in the exhibition is medieval, western or a codex (book-shaped) – or even manuscript (handwritten). Two manuscripts are shown closed; one is displayed upside down. Some mss are well known to scholarship and have been exhibited before; others are relatively unknown. All are catalogued (1-450 by RAB Mynors, 1963), but to widely varying degrees of detail and emphasis. Visitors may be surprised by the variation in the amount of documentation about not only conservation work but provenance and donation.

Focusing on the theme of damage and conservation removed possible restraints of e.g. period or subject, while avoiding a miscellaneous ‘Treasures of…’ approach. The manuscripts’ move to new premises was a good point in their history to assess their current condition and their needs for the foreseeable future, continuing to build on Balliol’s first several years as members of the Oxford Conservation Consortium.

Damage to manuscripts can occur at any stage of their existence – during production, while in storage, and in use (both voluntary and involuntary). I need only quote from the litany of woes turned up in the 2014 condition survey: dirt, losses, pest damage, staining, ink corrosion, text loss due to trimming, water damage, cockling, pleating, old repairs, smudging, ink fading/abrasion, ink offset, flaking gold, tears – to name a few. ‘Losses’ is a particularly painful catchall term including anything from a torn away corner to an excised illuminated initial to whole missing pages.

Conservators plan and carry out repairs to these amazing objects with great professional skill and enormous patience. Similar problems come up again and again, yet every case has to be treated individually, combining scientific understanding, practical knowledge and a creative approach. Much of their work is hidden inside a book’s binding once treatment is complete. Most items are not intended to, and do not, look ‘like new again’ after repair; they show their old scars as part of their material history, but are made safe to handle again (carefully) without causing immediate further damage.

In addition to repairs, however, the conservation team also help their members with advice and support on a wealth of related subjects: pest and environmental monitoring, preservation materials, all aspects of exhibition production, borrowing and loan of objects, transport, general and specialised handling and cleaning training for staff, loan of specialist equipment and advice on purchase, disaster preparedness and emergency response planning and training, and as we all do, career advice and visits for students.

Not every manuscript shown has been conserved – or at least not to modern standards – yet. The exhibition features a number of fine examples of the work of the Oxford Conservation Consortium and previous conservators known and unknown, but it marks a milestone rather than an endpoint. The OCC has been providing conservation services to Oxford’s special collections since 1990. Balliol joined it in 2006 at the instigation of Dr Penelope Bulloch, then Fellow Librarian, and with support from John Phillips and the Balliol Society. The OCC became an independent charity in 2014, and Balliol’s Archivist and Finance Bursar sit on its management committee. The OCC now cares for the historic collections of 17 colleges. They also maintain the Chantry Library of conservation-related publications, which is available to everyone.

A great advantage of OCC membership is the ability to plan not only a full year’s work but strategies and priorities for years to come. We have been able to move from a reactive programme of occasional work on individual manuscripts to proactive long-term planning that includes detailed conservation of key individual items but emphasises improving the condition and care of the collection as a whole.

Curatorial initiatives for the medieval manuscripts comprise a network of related projects:

Completed:

- 2014 condition survey

- boxing of all manuscripts (nearly 100) previously without boxes

- 2017 exhibition

Ongoing:

- Conservation treatment/repairs

- Replacement of old/worn/substandard boxes

- Improving descriptions and updating bibliography

- Digitisation for documentation & research

- Supporting teaching and research in person

- Documenting manuscript fragments in early printed books

- Workshops on correct handling of special collections material for students preparing for research using archives and manuscripts

The aim of all of these activities, and others as yet in the planning stages, is to improve preservation and access for all the manuscripts.

Preservation means ensuring the continued survival, and improved physical condition, care and handling of, all manuscripts. This is the responsibility of all staff and users of material. An archivist’s regular preservation tasks may include removal of rusty paperclips and staples, rehousing in acid-free archival quality folders and boxes, photography and scanning for cataloguing (to minimize use of the original), and training students and researchers in good handling practice.

Access is not only hands-on consultation of original material, but also improved access to better information about the manuscripts; images are an important source of information. It also includes improving understanding of the manuscripts as texts, physical objects and cultural products. Access is provided by staff and institutions, with input from researchers and scholarly publication.

Conservation means specialist professional treatment and repair of individual manuscripts, with the aim of ensuring that future careful handling/consultation/display does not actively cause further damage. Work is planned by staff in consultation with conservators, and carried out by the conservators.

Each of the manuscripts displayed is augmented by a number of prints from digital photographs, mostly enlarged details. While no facsimile edition or digital image can replace direct encounters with original manuscripts, they can support and augment research in person. An exhibition can only show one opening of a codex, or (usually) one side of an original document, at a time, in a single geographical place, to a limited number of people, for a limited period of time. Digital images can help to provide more access to information about, and contained within, the manuscripts, to more people in more places over a longer period. [more about digital images as tools for manuscript studies – not as substitutes for the original]

Digital photography of the manuscripts is carried out as part of my work as archivist, prioritised by researchers’ enquiries. Depending on the request and time available, I may photograph all or part of the manuscript, though in the case of part photography, ideally I will return later to complete the set. Images are sent to individual enquirers for ease of download, and also posted to Flickr at full resolution. Neither the original requester nor online users are charged for access to the images; widening access in practicable ways to collections that cannot be made generally available in person is part of the College’s obligations as a Charity, and of its aims as a higher education institution responsible for these historic collections. So far I have posted images of more than 100 of the medieval manuscripts online, many of them complete, in addition to some of the archives, personal papers, and key research resources, and the Balliol Flickr collections have had more than 2.5M views altogether (as of October 2017).

The supplementary images in each display case provide a window into other parts of the book and a magnified view of tiny details that can be hard to appreciate with the naked eye. If you are inspired by the original manuscripts on display to explore the wider world of manuscript studies, links to more images of these and many more of Balliol’s medieval manuscripts, and a starter list of print and online sources, are provided in the Further Reading post.

A note about display: I have chosen to display most of the manuscripts exhibited on the grey foam wedge supports we routinely use in the searchroom, with the pages in many cases held in place by fabric-covered lead pellets (known as ‘snakes’). Using ordinary supports shows a little of how we, curators and researchers, work with manuscripts; it looks less ‘produced’ than museum-style stands, but after all the collection is owned by a small institution and a very small department. Only a few sets are new for the exhibition, and all will be used after it. This saves huge amounts of specialist time, money and materials in making custom-fitted card or acrylic stands for each, and means that all the display materials will be used again for years to come, for research, teaching and future exhibitions, since the wedge sets can be used in interchangeable combinations to suit the size and opening angle of any volume. Only the four tiny books in case 9 needed their own stands made, as they had to be strapped into place to remain open.

I have also chosen not to print copies of the exhibition catalogue except for use while visiting in person; those who would like a hard copy are welcome to print the PDF version or any combination of the blog posts for their own use. Any exhibition of physical items is ephemeral, but a catalogue should have the lasting effect of opening the exhibits, though in an inevitably limited way, to a wider audience than could possibly attend the exhibition itself. An online catalogue can be accessed and printed at any time according to the needs of the user, and can also be augmented and corrected into the future.

I would like to thank Jane Eagan and her team of dedicated professional conservators at the Oxford Conservation Consortium for a decade of not only repairs to Balliol’s archives and manuscripts, and latterly to some of the early printed books as well, but also for their expert advice and support on all aspects of the material wellbeing of the historic collections, including environmental monitoring and amelioration, pest monitoring and treatment, local and international loans and exhibitions, project grant applications and planning.

I thank also Annaliese Griffiss for proof reading – all remaining errors are mine – and invaluable help preparing the exhibition, as well as her ongoing work on the Manuscript Fragments project, and Sian Witherden for good conversations about tiny books and for her contribution on book vandalism.

– Anna Sander, BA, MPhil, MScEcon, Archivist & Curator of Manuscripts, Balliol College

Photographs in this catalogue are by Anna Sander for Balliol College except where otherwise indicated.

The catalogue as printed for use by visitors to the exhibition is available as a PDF here. The print version is restricted to a single opening (one A4 double-page spread) per manuscript, which is as much as anybody can stand to read while walking round an exhibition; this online version, a series of blog posts tagged #mss2017, contains more detail and more images for most entries, as well as Further Reading sections for specific topics not included in the more general Further Reading post. The print version entries will also be used as Special Collections in Focus posters in Balliol Library and Holywell Manor during Michaelmas Term 2017.

#mss2017 Case 14: MS 384

MS 384, open to full page miniature of the martyrdom of St Thomas à Becket

MS 384, open to full page miniature of the martyrdom of St Thomas à Becket

MS 384 is a 15th century Flemish Book of Hours, made in the Low Countries for the English market according to the Use of Sarum. I am sometimes asked about the pre-Reformation liturgical books lost from the College chapel. Books of Hours would not have been among them – they were designed for the private devotions of secular individuals at home.

It is not known who gave the book to the College, or when, but from a note inside it, it was not at Balliol before the 18th century. It bears marks of having been a much-used family devotional book, and has a remarkable history ( or at least legend) of preservation against the odds; the anonymous donor writes: ‘The Book was found in the thatch of an old house… now my guess is that at the beginning of the Reformation, this Book was committed to Atkins of Weston to be secured ‘till a turn might happen… Pray Sir my humble service to Mr Harris and all friends at Colledge.’

MS 384 does corroborate this story in several ways: there is rather heavy, ingrained dirt across all surfaces, which would fit with its having been stored in the inevitably smoky thatch of a house. Burn marks on its lower edge might indicate a thatch fire – perhaps this is how it was rediscovered. It shows a few signs of contact with water, and of damp conditions. Otherwise, it is in remarkably good condition – it was rebound, probably in the 18th century, but does not show much evidence of earlier intervention in the text block. The only essential repair needed in 2017 was to secure a long tear across the lower part of f.70. unusually, this tear did not start at the edge of a page; rather, it looks as though a guideline ruled with a dry point may have (after several centuries) weakened an already thin and fragile area of parchment.

MS 384 – L, detail of miniature damaged by devotional kissing; R, rather dirty liquid damage from head edge

The other type of damage evident in this manuscript affects two miniatures, with similar partial removal of the faces of the central figures. Such damage to saints’ images, and sometimes to the associated texts, has often been assumed to be deliberate ‘de-face-ment’ by anti-Catholic reformers – but Kathryn Rudy and others have more recently asserted, with excellent evidence, that some such instances are the result of devotional kissing. Both Thomas à Becket (a frequent victim of the deliberate type of damage) and John the Baptist have suffered loss of paint here, but not of drawing or parchment surface – the painting has not been scratched or scraped, neither text nor image has been struck through, and the faces are still clear despite the smudging. Both also look as though the damaged areas have been somewhat damp. Viewers may draw their own conclusions!

work on MS 384 by Celia Withycombe of OCC: fine bridges of Japanese paper connect the edges of an irregular tear, 2017.

More about devotional damage in manuscripts:

- John Lowden, Manuscripts tour ‘Treasures known and unknown in the British Library’ – Kissing Images section

- Kathryn M. Rudy, “Dirty Books: Quantifying Patterns of Use in Medieval Manuscripts Using a Densitometer,” Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art 2:1-2 (Summer 2010) DOI: 10.5092/jhna.2010.2.1.1

More about defacement of images of Thomas of Canterbury (Thomas Becket):

- Sarah J Biggs, ‘Erasing Becket,’ British Library Medieval Manuscripts Blog, 2011.

- Cambridge University Library, ‘The Face Defaced,’ Bodily Memory section of Remembering the Reformation exhibition, 2009-2017. Individual author unidentified.

#mss2017 Case 3b: MS 350

MS350 opening ff 11v-12r (Herefordshire Domesday)

This manuscript of 170 folios includes three separate texts on Anglo-Norman legal subjects: a late 12th c copy of the Herefordshire section of Domesday book (first written in the late 11th c); an early 13th c copy of the earliest treatise on English common law ‘Treatise on the laws and customs of the kingdom of England in the time of King Henry II’, known simply as ‘Glanvill’ after its late 12th c author; and an early 14th c copy of ‘Britton’, the earliest summary of English law to be written in French, probably in the late 13th century. The first two texts are in Latin – with an Anglo-Norman French charm against snake bites appended to the end of the Domesday extract – and ‘Britton’ is in Anglo-Norman French. From the Herefordshire connection, Mynors thinks it likely to have been another gift to the College from George Coningesby, but there is no internal or external provenance documentation.

MS 350 is displayed open to ff. 11v-12r, part of the Herefordshire Domesday, with entries for the Wormelow and Elsdon hundreds. This opening shows surface dirt, particularly in channels from the head edge, liquid staining at the edges, and ink oxidation of the red initials – most have darkened from bright orange-red to silvery purple. Some of the red and green ink, though not blue, has come through from the verso. The manuscript was rebound, or at least recovered in white vellum (calf skin) in 1892, but this rebinding may have reused medieval wooden boards – it is impossible to tell from the outside. The manuscript is in generally good condition, and only needs some surface cleaning and repairs to the split parchment cover.

The ‘Glanvill’ text in MS 350 is heavily decorated with intricate penwork initials, but no other colours are used and there is no gold. Penwork decoration, the most common form of textual ornamentation in medieval manuscripts, is often done by the main scribe; in this case, the rubrics, red ink chapter headings/incipits/explicits both within the text and in the margins, seem to have been completed along with the main text, while the red and blue initial letters and exuberant decorative penwork were done later and perhaps by another hand. NB the different hues of red ink used, a darker red for the rubrics and a brighter orange red for the initials and decoration. The penwork of the initials Q (Quandoque) and U (Utroque) lace together in alternating colours, and in two places the rubrics and decorative flourishes run across each other.

The margins of this text are home to a good number and variety of lively penwork beasts and human faces many more than the lion, rabbit, goat and dragon featured here. Some grow out of the flourishes of initials, while others are separate figures, mostly in the lower margin, reaching up to feed on the red and blue foliage, and sometimes fruit. As is usual, though not universal, marginal figures appear without comment and seem unrelated to the text, though close study (anyone?) might reveal puns and wordplay – often decoration is (at least) a navigational tool and a memory aid.

More about the texts in this manuscript

- Domesday: online exhibition from The National Archives http://bit.ly/2hw6xRq. The Herefordshire section of Domesday as found in this manuscript was edited by VH Galbraith and J Tait as Heredfordshire Domesday, circa 1160-1170 (Pipe Roll Society, London 1950).

- Glanvill: explore http://www.earlyenglishlaws.ac.uk/

- Britton: HL Carson, ‘A Plea for the Study of Britton’ (1914) http://bit.ly/2huYfZK

- Anglo-Norman French language: hub for all things A-N http://www.anglo-norman.net/

- John Hudson, The Formation of the English Common Law: Law and Society in England from King Alfred to Magna Carta (Routledge, 2nd ed 2017) – a briefer distillation of his weightier tome on the subject, The Oxford History of the Laws of England (OUP, 2012).

MS 350 full set of images: http://bit.ly/2hsx9Fu

#mss2017 Case 9: tiny books, tiny writing

Sian Witherden has been working on tiny books as part of her Balliol DPhil research. She writes: ‘In this exhibition, four small Balliol manuscripts have been placed together in one display case. These books are not related to each other in any way besides their common size—they contain different texts, they are written in a variety of languages, and they hail from across the globe. However, the creators of all these books faced the same challenge: how do you produce a readable text on such a small scale? Each of these books is smaller than an adult’s hand, and this demands an impressive level of craftsmanship. In MS 348, for example, the scribe has managed to write letters that are just a millimetre or two in height. Creating ornamental initials and illuminations on this scale is an equally arduous task, and close-up photographs of these decorations reveals an astonishing level of detail and precision. ‘

Anna Sander: On the one hand, small books are easy to move, hide or pack away if necessary; not obviously useful for recycling as binding waste, as big sheets of parchment are, when no longer e.g. liturgically relevant; and often much-loved, beautiful, and highly personal items handed down through generations. On the other, they are easily misplaced, lost or stolen owing to their small size; highly attractive on the market, reluctant though an owner might be to sell; and rather chunky to handle because of their high proportion of height and width to thickness. Mechanically, their own weight will not help to ‘persuade’ a stiff binding to open further, and in this exhibition, it’s only the tiny books that need to be strapped in place in order to keep them open. They are made to be held in the hand, or perhaps both hands, used by one person. While big books are necessarily at the more expensive end of the book production scale because of the larger amount of parchment required to make them, tiny books are not necessarily less expensive, as they may be beautifully produced and highly decorated with expensive materials, and are sometimes written on very thin parchment which must have been even more difficult to make than regular sheep or calf.

The size of the text in these small books varies widely – while MS 348’s minute writing is closest in size to that of MS 148, a much larger book, that of the other three small books shown here is not especially small, and reasonably friendly to the naked reading eye. Though it’s especially striking to see a whole book in minute writing, tiny script is not unusual in manuscripts – it is often used for annotations, marginal comments, rubricator’s notes, and interlinear glosses (see e.g. MS 253). Was it done with the same pen as the larger main text? a tiny quill? a feather? a tiny brush? Did they have spectacles or magnifying glasses? There isn’t much evidence – descriptions and depictions of scriptoria and scribes’ equipment and practice are surprisingly few, and not always reliable. We are intrigued, and will add more evidence here as we find it.

More about tiny manuscript books

- J Weston, ‘Teeny Tiny Medieval Books,’ Medieval Fragments blog, December 2013

- L Miolo and A Hudson, ‘Size Matters,’ British Library Medieval blog, May 2016

#mss2017 Case 9d: MS 378

MS 378, open at ff.28-29, showing rubrics and stitching in the middle of a quire

MS 378, open at ff.28-29, showing rubrics and stitching in the middle of a quire

MS 378 is an undated volume of prayers to the Virgin Mary in Ethiopic, or Ge’ez, the liturgical language of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church. This is Balliol’s smallest manuscript book at only 2 ½ x 3 ½”, or 62 x 83mm. It is so tiny that its custom-made box is about four times the size of the book, with a recessed mount to hold it securely. One benefit of this rather larger and heavier box is that it’s easy to find on the shelf, to handle, and to keep track of during production and consultation – a box as small as the book might easily be hidden behind a larger one, or worse, dropped.

This manuscript is displayed closed in order to show its Ethiopic sewing, often known as Coptic style and distinct from later western binding techniques. The Copts, early Egyptian Christians, were the first to use the codex format, and their sewing method is still unsurpassed in simplicity and flexibility: a new Coptic binding can be opened a full 360 degrees.

The MS is in fairly good condition; the sewing is fragile and there is evidence of fairly recent repair to the attachment of the front board – what looks like a large stitch on the lower front cover – but other than some surface dirt it does not require further intervention. The paper label glued to the front cover, which MS 378 has in common with many of the others, is in the hand of EV Quinn, who began at Balliol as Assistant Librarian in 1940 and became Fellow Librarian in 1963, a post he held until 1982.

MS 378 is the only one in the collection known to have been given to the College by Benjamin Jowett from his own library, but there is no documentation in the archives about how he came to acquire it, or its previous provenance.

Although it is neither western nor medieval (as far as we know, at least), this manuscript has been included in the exhibition for two reasons: it shares many of the same conservation issues and endearing qualities as any tiny book, and it serves as a small signpost to another section of the collection that has hitherto suffered from lack of attention. As yet, many of Balliol’s 33 non-western manuscripts are still ‘closed books’: not yet accurately dated and without full descriptions of their contents, they have not been studied in detail and their research value has yet to be assessed. We hope that through recently established Balliol and Oxford contacts, and with good digital images emerging as useful tools, scholars in the relevant fields will soon be able to tell the College more about this part of the collection. Their entries in Mynors’ catalogue have been grouped together under their traditional label of ‘oriental manuscripts’ here.

MS 378, showing stitching, boards and binding

More about Ethiopic manuscripts and Ethiopic/Coptic sewing:

- Ethiopic Manuscripts Collections guide, Princeton University Library

- C Breay, ‘Getting under the covers of the St Cuthbert Gospel‘, British Library Medieval blog (2015) and images of the binding of the Cuthbert Gospel

- S Winslow, Ethiopic Manuscript Production (2011 exhibition, University of Toronto)

- Turning the Pages presentation of an illustrated Ethiopian Bible, British Library

#mss2017 Case 3a: MS 349

MS 349 medieval binding, showing spine and front cover – formerly red

We have begun with two examples of administrative documents created in the course of College business. MS 349 perhaps conforms more closely to the expected type of a medieval manuscript: in codex format, a 15th century copy on parchment, in several different English bookhands, of nine texts related to the office of priesthood, listed by Mynors.

This manuscript is, unusually, displayed closed in order to show the only surviving medieval binding in Balliol’s collection – and a modern gummed paper label in the unmistakable hand of EV Quinn, whose career in Balliol Library spanned 40 years in the 1940s-80s. Images are displayed to show a typical opening, some of the alum tawed supports showing through in places, and an illuminated initial using gold and colour.

MS 349 was bequeathed to Balliol by Dr George Coningesby (1692/3-1768, Balliol 1739) in 1768, and by then would have been an antiquarian gift rather than a contribution to the active contemporary College Library. Coningesby is the largest single donor of manuscripts (17 or 18) to the College after William Gray, a 15th century Bishop of Ely. He also left a large number of printed books to Balliol. Coningesby’s donations were just late enough to escape the wholesale rebinding of the medieval library in 1724-7, for which one Ned Doe was paid nearly £50. Most of the manuscripts are still bound in this 18th century half-calf (similar to suede); the bindings tend to be heavily glued and many have cracked and split, while the fuzzy covers are thin, and tear easily. MS 349’s boards still retain the metal furniture for an otherwise lost fore-edge clasp, but do not bear marks of any chain staple. Mynors notes that ‘The last mention of chaining in the library accounts falls in the year 1767-8, and an entry under 1791-2 ‘From Stone the Smith for old iron and brass’ probably marks the ending of the practice altogether.’

MS 349 – turnin showing something of the cover’s original bright red colour

Losses to the cover of MS 349 reveal a bevelled edge of the wooden board; there is also (old and inactive) woodworm damage, and the smooth pigskin cover has faded from its medieval red nearly back to the original pale brown, though an inner corner shows some remaining dye. While in many cases medieval sewing structures may survive within later rebindings, they are difficult to observe; full medieval bindings are rarer survivals and provide useful research opportunities.

edge of wooden board showing old insect damage

broken sewing supports, exposed within the volume

broken sewing supports, exposed within the volume

At some time there has been a modern repair of ff.121-122, a bifolium that had become detached from the textblock. Although there is some heavy cockling to folios at either end, and tears to spine folds in places, the book opens well and can be handled, carefully.

MS 349 – a typical opening

More about western medieval bindings:

- The Making of a Medieval Manuscript – Getty Museum, 2003

- Bindings section of Medieval Books, University of Nottingham

- Medieval & Early Modern Manuscripts: bookbinding terms, materials, methods and models, Yale University Library Conservation Department, 2015 [PDF]

- Shailor, B. The Medieval Book: Illustrated from the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. University of Toronto Press, 1991.

- Szirmai, JA. The Archaeology of Medieval Bookbinding. Ashgate, 1999, reissued 2016.

and see also resources under Medieval Manuscripts – Introduction on the Further Reading page

#mss2017 Case 1: Statutes of Dervorguilla, 1282.

College Archives D.4.1

Detail of the beginning of the Statutes: ‘Deruorgulla de Galwedia domina de Balliolo…’

We begin not with a codex but with a single sheet of parchment with a pendent seal, the usual format for individual medieval legal and administrative records. This is the first formal document laying out the constitution, governance and way of life of the scholars of Balliol College; it is issued in the name of Dervorguilla of Galloway, Lady de Balliol, and is dated at Botel (Buittle Castle, seat of the lords of Galloway, near the town of Dalbeattie in Dumfries & Galloway), on the octave of the Assumption of the glorious Virgin Mary (i.e. 22 August), in the year of grace 1282. The text is written, as usual for medieval charters and books alike, in heavily abbreviated Latin: in the first line above, ‘dna’ with a line above it is an abbreviation of ‘domina’, ‘lady’; ‘dilcis’ of ‘dilectis,’ ‘beloved’; ‘xro’ of ‘christo,’ ‘Christ’; etc. Some abbreviations are indicated by generic signs including a line above the remaining letters, or the apostrophe still used today, but many are systematically represented by specific characters or symbols: in the fourth line above, you will notice several words ending in ibȝ – the ȝ, which looks like the Middle English letter yogh or a long-tailed z, stands for -us, so the ending is -ibus, used in Latin for dative or ablative plurals. There are useful lists and dictionaries of medieval abbreviations, but any archivist or researcher who routinely deals with medieval documents memorizes the most frequently used ones. Understanding the generic abbreviations depends on good reading ability and a knowledge of the formulaic language and context-specific vocabulary used in the relevant form of medieval documents.

Statutes of 1282, face (front side) and dorse (back side). Photos by OCC, 2017.

The Statutes have required remarkably little repair over their 735 years and are still in extremely good condition: as the College’s key founding document they have always been carefully preserved, and as they were legally superseded by Sir Philip Somervyle’s statutes in 1340 they were not current for long enough to suffer much wear from actual use. Parchment, usually made from the prepared skin of sheep or young calves, can last longer than a millennium if kept away from heat, damp, direct sunlight and pests; iron gall ink if made correctly and similarly preserved lasts as well. The fate of wax seals is often less happy, as in addition to the vulnerabilities already mentioned, they are naturally highly brittle and fragile even under the best storage conditions.

This document will have been folded around its seal for much of its existence; this has helped to preserve both the text and the seal. It and many of the medieval title deeds were flattened, and a modern label affixed, in the late 19th century. The original fold lines are still readily visible.

The Statutes were mounted in an acid-free buffered housing inside a Perspex box frame by Judy Segall of the Bodleian Library’s Conservation Department in 1986, at the instance of Dr JH Jones, then Dean and Fellow Archivist of Balliol. This treatment protected the flattened document and its seal, and made it safe to produce for either research or College events.

1282 Statutes, 1986 mount showing silica gel desiccant crystals. Photo by OCC, 2017.

In 2017, Dervorguilla’s Statutes were lightly cleaned and rehoused in a new acid-free mount by Katerina Powell of OCC, with an outer box made by Bridget Mitchell of Arca Preservation.

Seal of Dervorguilla: L obverse (front), R reverse (back). Photos by OCC, 2017.

The seal attached to the 1282 Statutes is not the College seal but the personal seal of Dervorguilla herself. In her right hand she holds an escutcheon (shield) bearing the orle (shield outline shape) of the Balliol family; on the left, the lion of Galloway. The other two shields represent Dervorguilla’s powerful English family connections: on the left, three garbs (wheatsheaves) for the Earl of Chester; and on the right, two piles (wedges) meeting toward the base for the Earl of Huntingdon. The motto on the obverse (front) reads, clockwise from the top: + S’[IGILLUM] + DERVORGILLE DE BALLIOL FILIE ALANI DE GALEWAD’.’ [Seal of Dervorguilla de Balliol, daughter of Alan of Galloway.’] That on the reverse (back) gives her titles in reverse: ‘S’ DERVORGILLE DE GALEWAD’ DNE DE BALLIOLO’ [Seal of Dervorguilla of Galloway, Lady de Balliol].

The College’s shield, used in its official logo today and visible in various forms throughout the College site in Broad Street, is taken directly from that shown on the reverse of Dervorguilla’s seal, above: the arms of Balliol and Galloway impaled, with, unusually, those of the wife rather than the husband on the dominant dexter side – the right as held, though the left as viewed.

Further reading:

- F de Paravicini, Early History of Balliol College. 1891. (includes full transcript of Statutes, in Latin) online at archive.org

- HE Salter, The Oxford Deeds of Balliol College. 1913. online at archive.org

- Marjorie Drexler, ‘Dervorguilla of Galloway.’ Transactions of the Dumfriesshire and Galloway Natural History and Antiquarian Society LXXIX (3rd series) 2005, pp.101-146.

- JH Jones, A History of Balliol College. 2nd ed rev, 2005. (includes full English translation of Statutes)

- Two illustrated talks on the conservation of medieval charters and their seals by Martin Strebel of Atelier Strebel, presented at the Seal Conservation Round Table Congress Oxford, March 2007

- Amanda Beam. The Balliol Dynasty: 1210-1364. John Donald, 2008

- National Library of Wales, Seals in medieval Wales

- Imprint Project: a forensic and historical investigation of fingerprints on medieval seals, University of Lincoln

Manuscript Fragments in Early Printed Books

a selection of manuscript fragments inside Balliol’s early printed books

a selection of manuscript fragments inside Balliol’s early printed books

Balliol’s archivist and librarians are working together with researchers to collect information about manuscript fragments reused in the bindings of the college’s early printed books. This information has not been compiled at Balliol before, and while some manuscript fragments are well known in secondary literature, the college’s catalogue entries do not always include copy-specific details describing them – or even indicating their presence.

Fragments are usually located just inside the front and/or back covers of books, may consist of paper or parchment, and can occur as spine linings, stubs, pastedowns, tabs, and flyleaves – or even offsets, inky ghosts of vanished texts left on the facing page. All kinds of texts are reused; so far we have already noted full or nearly full pages of text, decorated, decorated initials, sections of medieval and early modern music notation, and parts of administrative documents and personal letters.

More about current research on manuscript fragments and binding waste

- Annaliese Griffiss on her current work on the Balliol project

- Images and descriptions from the ongoing Balliol project

- Beinecke Medieval Fragment and Binding Waste Project , Yale University

- Princeton University Library online exhibition about historic bookbindings, including a section on manuscript binding waste

- Digital Image Archive of Medieval Music (DIAMM)

- Erwin, Micah. “Fragments of Medieval Manuscripts in Printed Books: Crowdsourcing and Cataloging Medieval Manuscript Waste in the Book Collection of the Harry Ransom Center.” Manuscripta 60.2 (2016): 188-247. Brepols. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1484/J.MSS.5.111918

- Fragment identification crowdsourcing project – Harry Ransom Center, UTexas at Austin

- Fragmentarium: International Digital Research Lab for Medieval Manuscript Fragments , University of Fribourg

- Liz at the Beinecke – a graduate student’s Tumblr about bindings and binding waste, Yale University

- Lost Manuscripts – a project led by David Rundle at the Centre for Bibliographical History at the University of Essex, with particularly thorough and useful apparatus

Medieval Manuscripts: Michaelmas 2017 Exhibition further reading

A tiny sample of sources from a vast field in print and online, examples mostly in English and within the UK. Fortunately in a blog post I am not as limited as in print, and can add as many as I like, so do share your favourites.

Balliol’s Medieval Manuscripts Online

- Digital photographs of more than 150 manuscripts (so far) on Flickr

- RAB Mynors’ Catalogue of the Manuscripts of Balliol College Oxford (1963) with additions, corrections, new bibliography and links to images

- Previous displays, Special Collections in Focus features etc here on the blog

Medieval Manuscripts – Introduction

- Dianne Tillotson’s Medieval Writing site

- Quill by Erik Kwakkel and Giulio Menna

- Medieval Manuscript Manual, Central European University

- The Making of a Medieval Manuscript, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge UK

Palaeography and Diplomatic – reading old handwriting and understanding old documents (medieval & early modern)

- DigiPal – C11 English palaeography

- Dave Postles’ medieval and early modern palaeography training

- English Handwriting 1500-1700 – an online course (Cambridge)

- National Archives – Reading Old Documents resources

- Palaeography Training at Bangor University

- Scottish Handwriting

- Theleme (École des chartes, Paris) – Techniques pour l’Historien en Ligne : Études, Manuels, Exercices, Bibliographies [seulement disponible en français]

- Adfontes (University of Zurich) [nur auf deutsch]

Preservation and Conservation

- Bodleian Libraries Conservation Department (University of Oxford, UK)

- British Library Collection Care (formerly Preservation Advisory Centre, National Preservation Office)

- British Library, Medieval Manuscripts Blog, ‘Look on these works and frown?‘ May 2013, author not identified.

- Institute of Conservation (UK)

- Cornell University Library Conservation Blog

- The C Word – The Conservators’ Podcast

Old Manuscripts, New Science

-

- The Iron Gall Ink Website

- MINIARE Project – Manuscript Illumination: Non-Invasive Analysis, Research & Expertise

- Under Covers: the Art & Science of Book Conservation , UChicago Libraries Preservation Dept

- Digital Editing of Medieval Manuscripts 5 European university partners

- eCodicology – Algorithms for the Automatic Tagging of Medieval Manuscripts

- Old Books New Science Lab at the University of Toronto

Online research collections and exhibitions

- University of Pennsylvania

- Koninklijk Bibliotheek van Nederland

- British Library

- Digital Bodleian, Oxford (under construction 2017)

- Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

Medieval Manuscripts Blogs – Curators & Researchers

- British Library Medieval Manuscripts

- Erik Kwakkel

- David Rundle: Bonae Litterae

Printed Sources – Introduction to Medieval Manuscripts & Book History

- Christopher de Hamel, A History of Illuminated Manuscripts (1994)

- Jane Roberts, Guide to Scripts Used in English Writings Up to 1500 (2005)

- Raymond Clemens & Timothy Graham, Introduction to Manuscript Studies (2007)

- Ralph Hanna, Introducing English Medieval Book History: Manuscripts, Their Producers and Their Readers (2014)

- Alexandra Gillespie & Daniel Wakelin, eds. The Production of Books in England 1350-1500 (2014)

UK Academic & Professional Organisations

- Archives and Records Association (ARA), formerly Society of Archivists

- Association for Manuscripts & Archives in Research Collections

- CILIP Rare Books & Special Collections Group (RBSCG)

Oxford seminars & events

- Centre for the Study of the Book

- Seminar in Palaeography and Manuscript Studies events advertised termly on https://talks.ox.ac.uk

- Oxford Medieval Studies

If you use social media, #medievaltwitter is a lively and useful place to find all kinds of news and discussion of professional and academic issues for and by medievalists, including many of the scholars and institutions listed above. Try hashtags #manuscriptmonday #mondaymonsters #fragmentfriday #flyleaffriday

#mss2017 Case 10: MS 396

Guard-book (hardbound fascicule volume) containing five leaves of an early 14th century noted Sarum Breviary, written in two columns of 28 lines with large red and blue flourished capitals. These leaves were found and removed from the binding of an ‘old dilapidated’ College account book in 1898, by George Parker of the Bodleian Library, who was checking College records on behalf of a Mr Richardson.

In addition to the obvious holes in the parchment, the unknown early C20 conservator observed that the material was damaged and fragile throughout, and applied a then popular method known as silking, or chiffon repair: a fine silk gauze was glued to both sides of the parchment. This was considered less invasive than the other method available at the time, which covered the damaged area with translucent paper.

Detail of MS 396, darkened and contrast enhanced to show layers of silking – more visible where the parchment has been lost, but present over both sides of the full page.

Silking certainly reinforced the parchment while leaving the text and music largely visible from both sides, but it is hard to tell now how much of the brown discoloration may have been caused by the adhesives used in the silking process. The glue still gives off a distinct smell, but it would cause more damage to the leaves now to remove the silking than to leave it in place. The leaves are reasonably safe to consult as they are, so no further intervention will be made for now.

A breviary is one of the liturgical books used for the Office, the cycle of daily church services other than the Mass. It includes the text and musical notation, shown here in square black notes, known as neumes, on a red four-line stave. A direct descendant of this system, which indicates mode, pitch and relative note length, is still used for traditional Gregorian chant. Are these manuscript fragments related to any of the other pieces of liturgical manuscript recycled as binding waste in Balliol’s administrative records and early printed books, or elsewhere in Oxford? A question for future research…

More about Silking

- Kathpalia, YP. ‘Conservation and restoration of archive materials.’ UNESCO, 1973. [PDF]

- Krueger, H. ‘Silking’ section of ‘ The Core Collection of the Manuscript Division at the Library of Congress‘. Book & Paper Group Annual Vol. 14, 1995.

- ‘Preserving the Manuscript: Desilking “A Christmas Carol“‘, Thaw Conservation Center, The Morgan Library & Museum, 2011.

More about medieval musical liturgical manuscripts

- Hiley, D. Western Plainchant: A Handbook. OUP, 1995.

- Hughes, A. Medieval Manuscripts for Mass and Office: A Guide to Their Organization and Terminology. University of Toronto, 1995.

- Digital Image Archive of Medieval Music (DIAMM)

- Medieval Music Research Guide, Princeton University Library – lots of links to online image databases

- Sciacca, C. ‘Liturgical Manuscripts – an overview. ‘ British Library.