manuscripts boxing

The benefits of last year’s condition survey of manuscript books continue apace: during last year’s manuscripts condition survey, we listed 155 manuscripts either unboxed or inadequately boxed. Boxing is a quick and effective – and relatively inexpensive, depending on the type of box – way to protect all kinds of archival material from light, dust and handling damage, as well as providing a certain amount of buffering from the environment.

First batch of 25 to be measured – these manuscripts are in good condition and require only light cleaning. Once they are boxed they will not need further conservation attention for a good long time, we hope. This will mean we can cross two dozen off our list of 155 quickly. The next tranches of mss will be measured in batches as well, in order according to how much repair they need, starting with those needing least binding repair, and avoiding those needing major text block repairs until the end. This isn’t just about getting through the list quickly: any change to the binding – and even some major interventions to the text block – may alter the outer shape of the book and therefore the box. Those will need treatment before they can be accurately measured for a box. Some may need a folder or wrapper in the interim.

The first lot of custom-made boxes has arrived from the Bodleian’s boxing and packaging department:

a surprisingly small package…

contains a certain number of boxes…

which are bigger on the inside than the outside! clever packing 🙂

one type of box – drop-spine, mostly used for larger, thicker or hardback volumes; several have string-and-washer closures on the fore edge for extra security and a little pressure to help keep the boards in shape

the other type, a robust four-flap folder, for thinner, smaller and soft-back volumes

all done – another two dozen manuscripts safer on the shelf and during production!

manuscripts survey PS

Another use of last spring and summer’s survey of the medieval manuscripts: a researcher wanting to consult a long list of manuscripts, not necessarily in a particular order, had them produced by size, starting with the smallest. Result: only one swap to a different-sized set of foam book support wedges needed in a whole day’s research.

conservation – manuscripts survey summary

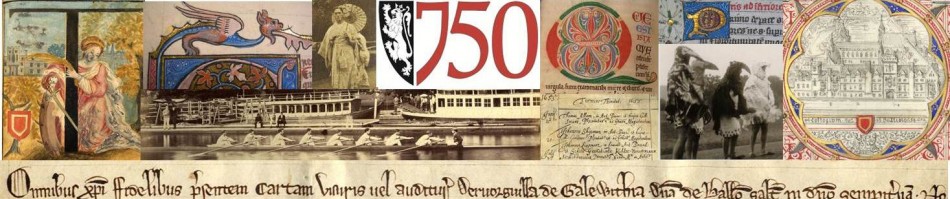

Balliol College Archives & Manuscripts and the Oxford Conservation Consortium recently completed a condition survey of all of Balliol’s medieval and early modern manuscript books, as well as a number of later items catalogued in the same series. (See RAB Mynors, Catalogue of the Manuscripts of Balliol College Oxford, OUP 1963.)

The survey of 497 items, ranging from single sheets and home made booklets of a few bifolia to palm leaves strung between wooden boards and huge bound volumes on parchment, took 39 sessions averaging 3 hours each (ca 120 hours total, more than 4 items per hour) over 29 weeks, from mid-January to the end of July 2014. The staff hours required were twice that, as each session required two people: a conservator handling the manuscripts and a Balliol staff member entering data into an Access database on the OCC laptop. This was a much more efficient use of the college’s OCC subscription time than having the conservator enter the data as well as assess the manuscripts. It also provided a once-in-a-career opportunity for Balliol Library staff, particularly the Archivist, who is responsible for the manuscripts, to become familiar with every manuscript in the collection, in some detail. Most of the data was entered by the Archivist, but all members of Library staff participated during the course of the survey, as did five members of OCC staff. The process was speeded up considerably by having the 10-15 items scheduled for each day’s session ready in advance and waiting on a trolley in the reading room when the conservator arrived.

The survey

Each item received an average of 15 minutes of assessment, but in practice it varied from 10-25 mins depending on the complexity and condition of the item. The survey template included sections for descriptions of each item and assessment of its current physical condition as well as recommended repair/conservation treatment: survey information (date seen and name of assessing conservator); physical dimensions; current boxing or other container; text block materials, binding type, cover and board materials; attachments and supports, sewing, endbands, fastenings, text block edges, binding decoration, labels or titles; condition of text block and its media; condition of binding (cover, boards, joints, sewing, endbands, labels); whether the volume had been rebound or rebacked; its overall condition or usability; any treatment required or recommended, including new or replacement preservation boxing/packaging; and any other notes.

Equipment required

- good lighting and seating, a large stable table

- large document trolley

- measuring tape

- conservator’s tools e.g. large tweezers, selection of dentistry tools!

- magnifying glass

- cold (LED) desk lamp

- foam wedge book supports of various sizes

- bone folders

- lead weight/snakes

- laptop for entering data

The database

The template for the survey database was adapted for the Balliol survey into Access format from OCC’s existing Word document, which had been used for several previous similar surveys at other colleges. We also kept a paper copy of the form handy during survey sessions for easy reference to descriptors. It was pre-loaded with all the MSS numbers, short titles for identification and centuries of production. At the end of each session the updated database was copied to a memory stick and to the archivist’s networked drive.

Having the survey information in a database format, not only electronically searchable but also sortable, makes possible many of the future uses of the data listed below.

Database suggestions

We found that while the template provided an excellent structure for focused investigations and vocabulary for nearly everything we needed to describe, it would have been useful to have a notes field as well as tick-boxes for description of the writing materials. Most texts fell into the usual categories of iron-gall ink, black-brown ink, pigments etc, but we also found various types of ‘pencil’ in some of the medieval books, and modern inks, pencil and typescript in some of the modern mss. In some cases we noted these in the Notes field at the end, but more information would have been captured with another field in the writing materials section. The same applied to the Bindings description section, especially for some of the unusual amateur bindings and coverings. We began noting the number of binding supports partway through and found it a useful addition.

Data entry was done directly into the Table view of the Access database; this helped to keep investigations very focussed, as the Table view layout made it difficult for the data enterer to skip around between sections, but an Access user interface would give access to more fields at once and should be considered for future use. Some users might prefer to convert the database to Excel, and we have found it useful to extract and convert parts of it to Word for reports and printing.

Aside from the professional and custodial benefits to staff and the college, we all enjoyed this survey immensely! It was an exciting time of (re)discoveries in the collection and much learning for all involved.

Benefits and uses

1) The most obvious function of the survey is to inform conservation treatment priorities for the future, but it is far from the only one. For each manuscript, its current condition and recommended treatment will be balanced with its contents/research interest and likelihood of exhibition or teaching use. We have good data going back more than 10 years on the ‘research popularity’ of the manuscripts.

2) In addition to conservation treatments needed, the survey has identified basic important preservation improvements e.g. numerous mss are not yet boxed, or need wrappers inside their otherwise good acid-free envelopes

3) The survey acts as a shelf check of the manuscripts.

4) Although the manuscripts were catalogued by Mynors, some of the descriptions date from as early as the 1930s and many reflect Mynors’ own research interests, heavily biased toward the texts of western medieval books. The survey has helped to identify underdescribed manuscripts needing improved catalogue entries to serve the wider interests of students of codicology and the history of the book. Areas particularly needing improvement are descriptions of historic bindings, details of illumination and book decoration, early modern manuscripts and non-western manuscripts.

5) Electronic records make it easy to flag the manuscripts’ physical condition to potential users on our website, so it is clear in advance which need (extra) special care in handling and which (few) will not be produced to researchers in their present condition. This will inform staff handling and manuscript-specific instructions on handling to readers. Better handling will improve long term preservation by decreasing the likelihood of further damage.

6) Similarly, exhibition/loan requests can receive quick and detailed responses about the suitability of specific mss for display and particular considerations needed. Where necessary, treatments can be prioritised or alternative candidates found. Staff will be able to balance the physical exposure of manuscripts across the collection rather than repeatedly displaying the same few well-known and regularly requested ‘treasures’. Increasing the breadth of manuscripts displayed will lead to institutional appreciation of the collection as a whole rather than a set of highlights with an anonymous hinterland of unknown quality.

7) Staff can easily find FAQ statistics e.g. largest, smallest, oldest, unusual characteristics, shared features, authors, texts, dates; these will be useful for reports, teaching, outreach, displays and online features.

8) Improved staff/institutional knowledge of the whole collection has already led to use of some of the less-frequently consulted (and formerly less valued) manuscripts for teaching and school outreach purposes.

More benefits and further uses of the survey are still emerging:

- Conservators are adapting database template for use in similar surveys with other colleges.

- a research-experienced volunteer is gaining curatorial experience and starting improvements to descriptions of codicological and decorative features to support teaching, research and exhibition requirements (see (4) above).

- an academic researcher has been provided with the most complete list available to date of all Balliol manuscripts within a date range containing illumination (in this case, decoration using pigments and metal e.g. gold leaf). The list derived for these criteria from the survey database is considerably longer than any comparable list yet in print.

A few survey numbers

- MSS surveyed: 497

- people involved: 9

- staff hours: ca. 240 (ca. 120 each Balliol and OCC)

- no. & % of mss in good condition: 211

- no. & % of mss in fair condition: 196 + 22 in ‘fair-to-good’ condition, indicating that some minor repairs would make the manuscript significantly safer to produce.

- no. & % of mss in poor condition: 38 + 24 in ‘fair-to-poor’ condition, usually meaning that one of the boards is detached but the MS is in otherwise fair condition

- no. & % of mss in unusable condition: 6

- largest MS: two answers: largest volume MS 228, dimensions 480x350x125 mm, vol 0.021 m3; and largest boards MS 174, dimensions 480x370x090 mm, vol 0.0159 m3 .

- smallest MS: MS 378, a book of prayers in Ethiopic, written on parchment with wooden boards and a nice example of Coptic binding. It measures 081x062x035 mm.

- oldest MS: MS 306, part of which is a 10th century copy of a text by Boethius

Have a look at our conservation survey series of posts for more details of our discoveries! Still more to come…

conservation survey completed

We have just finished the last session of the manuscripts condition survey! 500 items spanning a millennium (10th-20th centuries), mostly codex format (i.e. books), mostly western European, mostly medieval, individually surveyed between mid-January and the end of July.

Only 40 are in poor physical condition, and only 6 are currently unusable – that is, any handling would cause further damage. The rest are in fair to good condition, and a number of those in poor condition require fairly straightforward repairs that will make them safe to handle (with care, of course).

It’s been a fascinating once-in-a-career journey through every single manuscript in the collection, and there are still many blog posts to come about our explorations and discoveries. The survey will inform not only future schedules for MS repairs starting this year, but also loans, exhibitions (it will itself be the subject of an exhibition), photography, outreach & teaching, further cataloguing/description…

Many MANY thanks to our wonderful team of professional conservators at the Oxford Conservation Consortium just down the road!

conservation survey notes 13

Balliol MS 385 is written in Pali on lacquered and gilt palm leaves enclosed and strung between painted wooden boards.

Detail of one of the boards

The inner side of one board and the outside leaf

Detail of an outer leaf

leaves from the middle of the manuscript, with text and decoration

detail of decorated leaf

Balliol has few Oriental manuscripts – the term under which all the non-western mss in languages and scripts from Pali to Persian, Hebrew to Hindi, have been lumped together. Most of them were given individually to the College as antiquarian curiosities, and they have not, on the whole, been evaluated, described or studied much at all in comparison with the collection of western manuscripts. But there are discoveries still to be made!

A description of MSS 385 and 386 by Prof FW Thomas, cited by Mynors as ‘kept with the MSS’, is lost, so as far as we know Balliol does not have information about the date or origins of this MS. There is no obvious documentation of how it came to Balliol, but there is a lot of acquisition information, at least for the 20th century, in the Annual Record, so we will at least survey that to see what we can discover.

In the meantime, our descriptions remain inadequate, but thanks to the efforts of archives, libraries and museums to put images from their own collections online, it is possible to put these ‘Balliol orphans’ in some kind of context with other manuscripts of their kind(s). I have found some (to the untrained eye at least) similar manuscripts – and therefore several useful descriptors and explanations of particular features – at:

- Trinity College Dublin Digital Collections (Dublin, Ireland) – try searching for ‘manuscript’ and then add Hebrew, Arabic, etc. This post from M&ArL@TCD’s blog about a Pali MS from Burma has images of something similar to Balliol 385.

- Walters Art Museum Illuminated Manuscripts (Baltimore, MD, USA) image collections on Flickr – includes a large collection of Islamic manuscripts

- The Wellcome Library (London, UK) image collection – search for e.g. ‘Pali’

- Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, NY, USA) – a small online exhibition on ‘Early Buddhist Manuscript Painting: The Palm-Leaf Tradition’

- Northern Illinois University (DeKalb, IL, USA) – manuscript collections in their Southeast Asia Digital Library

Very little of the British Library’s large Southeast Asia collections is online, either images or descriptions, but you can find some images here: http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Default.aspx

For background knowledge rather than images:

- The Fragile Palm Leaves Foundation

- The Pali Text Society

- The Wellcome Library’s Catalogue of the Burmese-Pali and Burmese Manuscripts

conservation survey notes 12

Balliol MS 452 is a copy of the Koran, given to the College in 1983. The donor did not have information about its date or provenance. We will be asking experts in the field(s) to examine Balliol’s small collection of Oriental manuscripts and describe them in detail, most for the first time. Watch this space!

Physically, the book is currently in unusable condition. The spine and one cover are detached, and the unsupported sewing is weak with some breaks, making the textblock unstable. Any use in this state causes damage – we disturbed it as little and as briefly as possible for this examination, while documenting as much as we safely could.

The first folio features areas of illumination using gold and pigments above and below the text and on two, perhaps formerly three, sides of the border. This page shows some old repairs, of which there are many throughout the volume.

above, showing f1 with the blue linen spine lining exposed

The two sections of the fore edge flap have become detached, and the hinges between the three parts of the cover are mostly lost.

The red leather cover, now darkened, was painted with silver and gold or pigments resembling metals. The various layers, which would not have been visible when the book was new, are now showing more clearly as the materials age and wear.

The small square gold-coloured areas are made separately and stuck on – some are beginning to lift as the adhesives lose their strength.

A view of one of the endbands, showing the typical zigzag pattern, now broken about halfway.

This volume was housed until recently inside what was once a beautiful dark green silk velvet bag, evidently specially made for it. A stub remains from the bag’s lost tie, in a rather natty check or plaid. The textile itself needs conservation, and removing the book from the enclosure or replacing it is only causing further damage to both items, so they will be kept separately – but still together. Ideally, one both items have been treated they could be housed in separate areas of the same box.

Thanks to the survey, we hope that both the history and the future of this book will soon become clearer!

conservation survey notes 11

Just a nice picture today – one of the great pleasures (and professional interests, obviously) of this survey is just looking through all the books, comparing hands and artistic styles, picking up patterns, similarities and differences. Balliol’s collection, on average, is not particularly generously or well decorated, but there have been some lovely surprises, like this. MS 232A has only one initial this elaborate. Most elaborately decorated first folios in Balliol’s mss have either been cut out entirely or lost their initial, head and bas-de-page. Some of this may have been out and out vandalism, someone stealing the initials for his own purposes, but particularly the top and bottom margins may have been cut out to remove marks of former ownership. Which raises questions about why anyone would bother to do that, but we are unlikely to come across an answer to that one.

conservation survey notes 10

Balliol MS 86 provides three examples of two types of book marker:

1) A strip of parchment cut from the edge of the page, folded and slotted through a small cut to form a little tab that sticks out beyond the edge of the page – very similar to the standard pendent seal attachment method on title deeds and other administrative documents.

above, the verso of 1

2) two examples of large stitches of coloured thread used as page markers. The question is, were the stitches themselves the marker, or did they once hold something else – a bit of cloth, parchment or paper – to the page? We may find another example that answers this question in another manuscript later. This is becoming quite a pattern – one manuscript will raise a question without providing quite enough evidence to decide on an answer, and then either another particular observation or an average of several similar situations will make the first example clearer when we take another, more experienced, look. Exciting – we are all learning a lot!

conservation survey notes 9

Today’s example, from Balliol MS 219, is textual rather than codicological: a rebus or visual pun. On f238v the gift of the book to Balliol Library is recorded by Master (i.e., MA, or perhaps Master as in head of house, as he also held that office) Richard Stapylton, formerly a Fellow of Balliol. Mynors notes, ‘The presence on 231v,… of R and two tuns (barrels) connected by staples (3-sided or U-shaped fastening), apparently drawn by the rubricator of the volume, suggests that it was written for the donor, and comparison with the Digby MS [Oxford Bodleian Library Digby 29] shows that at any rate [a] great part of it is in his hand.’ More details about Stapilton [sic] in Emden’s Biographical Register vol 3 p.1766.

Ho ho ho.

conservation survey notes 8

Today we have some rather unedifying graffiti in Balliol MS 218 – what looks like a child’s drawing in pencil (or other sort of lead point) of one man hitting another on the nose with ?a stick. It may even be by a child – the children of an 18th century Master have left numerous traces in the college library collections, often carefully signed with their names…

Other things of note on this page – well, quite a few different stains. Several layers of commentary and annotations – main text in the middle column, comments to right and left, further notes in the outside margin – I like the triangular ones, not sure whether they have a particular significance. And lots of interlinear interpolations. Prick marks, one of the early steps in laying out the page for writing, are visible down both outside and inside edges of the pages. Just above halfway down the right-hand page (84r) is another example of a production cut, where a stitched mend has been cut out before writing.

Other things of note on this page – well, quite a few different stains. Several layers of commentary and annotations – main text in the middle column, comments to right and left, further notes in the outside margin – I like the triangular ones, not sure whether they have a particular significance. And lots of interlinear interpolations. Prick marks, one of the early steps in laying out the page for writing, are visible down both outside and inside edges of the pages. Just above halfway down the right-hand page (84r) is another example of a production cut, where a stitched mend has been cut out before writing.

conservation survey notes 7

It’s usual to come across occasional production repairs of parchment in medieval books, but today’s example (Balliol MS 210) we immediately named Frankenbook! There are numerous pages with multiple stitched tears each, and in most cases the stitches have been left in, leaving long, bumpy dents in the facing page.

It’s usual to come across occasional production repairs of parchment in medieval books, but today’s example (Balliol MS 210) we immediately named Frankenbook! There are numerous pages with multiple stitched tears each, and in most cases the stitches have been left in, leaving long, bumpy dents in the facing page.

The parchment-making process involves a lot of scraping and stretching, so tears in the skin are inevitable during production – they are usually stitched up while the skin is still wet. I’m reliably informed that this is very difficult, and the sewing as a result is often rather crude. The stitched area tends to be lumpy when dried, and the stitches themselves are often removed at a later stage to make the page lie flatter against its neighbours. This can leave either a slit edged on two sides by stitch holes, or a narrow rectangular hole (example in the photo above). It is often clear that these cuts/repairs have been made before the book was written because the text is written around the hole – example below, leaving space around the ‘scarred’ area. In this case the stitches have been scraped rather than removed, but the surface is still not flat enough for writing on.

conservation survey notes 6

Today’s image is a cheerful early 13th century author portrait of St Bernard of Clairvaux, to begin Balliol MS 150, a volume of his sermons – and we begin with a sermon ‘in adventu Dominica prima’, for the first Sunday in Advent, the church’s new year. The point to today is a photographic one, illustrating a very basic technique that makes a big difference to large photos of small things: if the camera is placed very close to the subject, among other issues there will be quite a lot of distortion (‘barrelling’) around the edges of the photo. A way round this is to zoom in, even a little bit – the photo below has much straighter edges, truer to the original. The lines in the manuscript aren’t straight, and any photo will also show the cockling on the page, but the zoomed photo is certainly better.

From a conservation point of view, this is a good illustration of effects of oxygen and/or humidity on pigments – the sequence of long triangles down the sides of the blue capital H used to be all the same shade of red, but parts have oxidised, turning the surface purple.

conservation survey notes 5

from Balliol MS 250 – the scribal hand (or another, but not a formal decorator) has added huge numbers of these informal but charming penwork illustrations, particularly to letters that extend up or down into the margins. Perhaps the text, Aristotle’s De historiis animalium, has some influence on the choice of decoration, but if so it’s not specific, as the bird drawings occur throughout but are the subject of only Book 6. In the illustration above, three birds are sitting in a tree or bush, probably intent on eating the berries represented in the middle part of the plant. Another creature is also trying to get in on the act – perhaps a rabbit, pig or dog. Birds eating grapes often turn up in much fancier illuminated borders. I’d like to see some proper research on the ornaments in this manuscript, but it looks to me as though the illustrator is drawing from figures and little compositions commonly found in much higher-status ornamentation, not only the birds eating grapes but rabbits munching on leaves, dogs chasing rabbits, grotesques and faces growing out of foliage – quasi-Green Men.

Here, several clearly different species of bird going after berries. More from this charming manuscript soon, I hope!

conservation survey notes 4

Today we have naming of parts – binding parts.

Balliol MS 248C – the front board is detached, held on only by the cloth lining the inner joint.

And here’s why – although the double alum tawed supports are clearly present in the spine…

… when the manuscript was rebound, the supports were cut, and not attached to the upper board at all. The leather covering the outer joint, which was doing a lot of the work of holding the board in place, has, unsurprisingly, split under the strain.

Close up showing the stumps of the supports on the spine side (lower part of photo) and the channels cut into the board for the supports to continue into – but the channels are empty! The linen inner joint, now damaged itself, is the only attachment between spine and board.

conservation survey notes 3

Today’s feature comes from MS 151 (a 13th century copy of letters by St Bernard of Clairvaux), f 161r – rubricator’s notes. At the very edge of the bottom of most pages are tiny notes. These will have been made by the scribe as he went along, to indicate the text for headings and anything else that needed to be added in red, for which he left spaces in the (black) main text.

Then he or another scribe went back through the text, adding paragraph marks, initials, headings and other decoration, usually (as here) in alternating red and blue inks. The rubrication notes were placed right on the edge of the parchment because they were always intended to be trimmed off, and they usually are – occasionally one that wasn’t quite close enough to the edge will remain, or at least the tops of the letters will, after trimming, but it’s rare to have them present, as in this one, throughout the manuscript.

Further decoration such as marginal foliage or figures, historiated initials etc, using more pigments and sometimes gold, (not present in this ms) was yet another layer of time and therefore expense in the book production process. Scribe, rubricator and limner were three distinct roles that might all be done by the same person, or by two or three different individuals.

conservation survey notes 2

Several things to say about Balliol MS 149, a 14th century collection of sermons – on f 122r, the most eye-catching feature is the big manicula, aka Nota Bene hands, used as pointers the way we might use arrows, highlighting, underlining etc. How many fingers??

The handwriting is also notable – more or less a documentary hand such as we would expect to find in charters and other administrative documents, here unusually used in a formal book context. And lots of different types of text correction: rubbing out and writing over, superscript interpolations indicated by the still-current caret ^, dotting under the word to be deleted, crossing out… why has crossing out survived and expunction (underdotting) not? More about types of errors and corrections and technical notes on same – see especially IV.vii and V.ii.

more about manuscripts

Updating our online lists of Balliol’s medieval manuscripts: the condition survey of medieval books is progressing well. Each time we finish another 50, the descriptor [good/fair/poor/unusable] is added to its list entry in square brackets, to indicate its current physical condition as assessed by Oxford Conservation Consortium staff in 2014. Those in Poor condition will not normally be produced for researchers, and those rated Unusable not produced at all, until conservation treatment has been carried out in order to prevent further damage during consultation. Poor or Unusable manuscripts may also not be fit to photograph safely, including by staff. If you do want to consult or request images from a manuscript that is not currently in a state to produce or photograph safely, please let us know – active research interest is of course a key factor in determining our conservation priorities.

This doesn’t mean that currently Poor or Unusable manuscripts will be inaccessible forevermore. The survey is being undertaken specifically to inform our decisions about what needs conservation treatment most urgently, and it stands to reason that those in the worst condition and which attract active research interest are most likely to be high on the list.

Neither does it mean that Fair or Good manuscripts can be handled with joyous abandon. (After all, they are all at least 500 years old in order to qualify for the title ‘medieval’.) Production of manuscripts is always at staff discretion, and readers are expected to arrive with good handling skills and/or be instructed in them – and put them to use!

More ‘before’ pictures of Interesting Problems in manuscripts coming shortly – and starting next year, we look forward to posting ‘after’ pictures of the ‘ex-poor’!

conservation survey notes 1

A new series of illustrated posts inspired by interesting things encountered during the condition survey of Balliol’s medieval manuscripts – a bookworm’s-eye view of common and unusual problems and solutions, if you will. We begin with Balliol MS 156 (12 century Jerome on Isiaiah), f 2v.

At first glance the text looks rather abraded, as though it has been rubbed. But lift the page and the real problem becomes clear…

Classic iron-gall ink corrosion – the ink was made too acidic and has eaten away the parchment, leaving more or less, and in some cases letter-precisely, text-shaped holes. Fortunately, in this manuscript at least the problem does not continue past the first few folios – somebody must have made a new pot of ink with rather less acidic proportions! Also clearly visible here are several old parchment fills or repairs at the edges of the page.