Digital images of medieval manuscripts

What an encouraging tweet exchange this morning:

Daniel Wakelin @DanielWakelin1

@balliolarchives Balliol’s energetic use of Flickr was one of our inspirations to experiment with this medium for #DIYdigitization @BDLSS.

Balliol Archivist @balliolarchives

@DanielWakelin1 @BDLSS WOW. That has made my day.

Daniel Wakelin @DanielWakelin1

@balliolarchives Truly. Your ‘roll up my sleeves and get on with it’ process of #DIYdigitization. @BDLSS may want to interview you about it.

Balliol Archivist @balliolarchives

@DanielWakelin1 @BDLSS Always happy to talk about opening access to manuscripts 😀

YES. Big grants are great but one person with one camera can get a lot done even in an hour or two here and there (my photography has to fit in along with all the rest of the job) and make a real difference – and, it seems, not just to the individual researchers who request particular images but to institutional policy and approaches to openness of access. Lovely to find my hunch (gut feeling/considered professional opinion) is turning out to be correct. Keep on clicking!

#DIYdigitization

Do you have photos of manuscripts held in Oxford’s Bodleian Libraries? now you can make them available to other researchers via their Special Collections #DIYdigitization group: have a look! https://www.flickr.com/groups/bodspecialcollections

There are instructions for naming/shelfmarking/tagging your uploads so others can find them, and so photos of the same ms from different contributors can find each other.

Balliol researchers are encouraged to do the same https://www.flickr.com/photos/balliolarchivist/collections/72157631849081491/

Opening access to archives and manuscripts, one click at a time…

manuscripts survey PS

Another use of last spring and summer’s survey of the medieval manuscripts: a researcher wanting to consult a long list of manuscripts, not necessarily in a particular order, had them produced by size, starting with the smallest. Result: only one swap to a different-sized set of foam book support wedges needed in a whole day’s research.

Family History enquiries

Looking for information about an individual who may have been a member of Balliol College? Here’s how:

(1) Balliol biographical research resources – see also the University Archives’ helpful links to several of the same sources.

(2) AE Emden, A Biographical Register of the University of Oxford to AD 1500 (3 vols, 1957) and a supplementary volume 1501 to 1540 (1974). (Print resource only)

(3) Joseph Foster, Alumni Oxonienses 1514-1700 and 1700-1886

(4) Oxford University Archives

(5) Oxford University Calendar and the Oxford University Degrees Office

(6) Oxford Archivists’ Consortium (OAC) – contact details for all college archives and other local resources

Open Days this weekend!

Balliol College’s Historic Collections Centre at St Cross Church, Holywell

will be open to the public as part of Oxfordshire Historic Churches Trust Ride & Stride

Saturday 13 September 2014 12-4 pm

and

Oxford Open Doors (Oxford Preservation Trust in partnership with the University of Oxford)

Saturday & Sunday 13-14 September, 12-4pm both days

There will be an exhibition in the church about the Balliol Boys’ Club and the First World War – more information on p.31

These events are of course FREE!

Ride & Stride participants, please note that the church will not be open during the whole official event time of 10am – 6pm – please come and visit us between 12-4pm.

Directions: http://archives.balliol.ox.ac.uk/Services/visit.asp#f

conservation – manuscripts survey summary

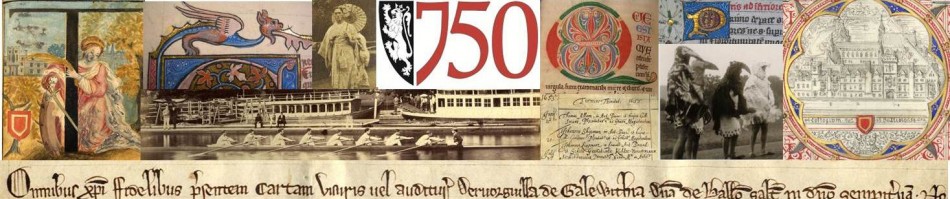

Balliol College Archives & Manuscripts and the Oxford Conservation Consortium recently completed a condition survey of all of Balliol’s medieval and early modern manuscript books, as well as a number of later items catalogued in the same series. (See RAB Mynors, Catalogue of the Manuscripts of Balliol College Oxford, OUP 1963.)

The survey of 497 items, ranging from single sheets and home made booklets of a few bifolia to palm leaves strung between wooden boards and huge bound volumes on parchment, took 39 sessions averaging 3 hours each (ca 120 hours total, more than 4 items per hour) over 29 weeks, from mid-January to the end of July 2014. The staff hours required were twice that, as each session required two people: a conservator handling the manuscripts and a Balliol staff member entering data into an Access database on the OCC laptop. This was a much more efficient use of the college’s OCC subscription time than having the conservator enter the data as well as assess the manuscripts. It also provided a once-in-a-career opportunity for Balliol Library staff, particularly the Archivist, who is responsible for the manuscripts, to become familiar with every manuscript in the collection, in some detail. Most of the data was entered by the Archivist, but all members of Library staff participated during the course of the survey, as did five members of OCC staff. The process was speeded up considerably by having the 10-15 items scheduled for each day’s session ready in advance and waiting on a trolley in the reading room when the conservator arrived.

The survey

Each item received an average of 15 minutes of assessment, but in practice it varied from 10-25 mins depending on the complexity and condition of the item. The survey template included sections for descriptions of each item and assessment of its current physical condition as well as recommended repair/conservation treatment: survey information (date seen and name of assessing conservator); physical dimensions; current boxing or other container; text block materials, binding type, cover and board materials; attachments and supports, sewing, endbands, fastenings, text block edges, binding decoration, labels or titles; condition of text block and its media; condition of binding (cover, boards, joints, sewing, endbands, labels); whether the volume had been rebound or rebacked; its overall condition or usability; any treatment required or recommended, including new or replacement preservation boxing/packaging; and any other notes.

Equipment required

- good lighting and seating, a large stable table

- large document trolley

- measuring tape

- conservator’s tools e.g. large tweezers, selection of dentistry tools!

- magnifying glass

- cold (LED) desk lamp

- foam wedge book supports of various sizes

- bone folders

- lead weight/snakes

- laptop for entering data

The database

The template for the survey database was adapted for the Balliol survey into Access format from OCC’s existing Word document, which had been used for several previous similar surveys at other colleges. We also kept a paper copy of the form handy during survey sessions for easy reference to descriptors. It was pre-loaded with all the MSS numbers, short titles for identification and centuries of production. At the end of each session the updated database was copied to a memory stick and to the archivist’s networked drive.

Having the survey information in a database format, not only electronically searchable but also sortable, makes possible many of the future uses of the data listed below.

Database suggestions

We found that while the template provided an excellent structure for focused investigations and vocabulary for nearly everything we needed to describe, it would have been useful to have a notes field as well as tick-boxes for description of the writing materials. Most texts fell into the usual categories of iron-gall ink, black-brown ink, pigments etc, but we also found various types of ‘pencil’ in some of the medieval books, and modern inks, pencil and typescript in some of the modern mss. In some cases we noted these in the Notes field at the end, but more information would have been captured with another field in the writing materials section. The same applied to the Bindings description section, especially for some of the unusual amateur bindings and coverings. We began noting the number of binding supports partway through and found it a useful addition.

Data entry was done directly into the Table view of the Access database; this helped to keep investigations very focussed, as the Table view layout made it difficult for the data enterer to skip around between sections, but an Access user interface would give access to more fields at once and should be considered for future use. Some users might prefer to convert the database to Excel, and we have found it useful to extract and convert parts of it to Word for reports and printing.

Aside from the professional and custodial benefits to staff and the college, we all enjoyed this survey immensely! It was an exciting time of (re)discoveries in the collection and much learning for all involved.

Benefits and uses

1) The most obvious function of the survey is to inform conservation treatment priorities for the future, but it is far from the only one. For each manuscript, its current condition and recommended treatment will be balanced with its contents/research interest and likelihood of exhibition or teaching use. We have good data going back more than 10 years on the ‘research popularity’ of the manuscripts.

2) In addition to conservation treatments needed, the survey has identified basic important preservation improvements e.g. numerous mss are not yet boxed, or need wrappers inside their otherwise good acid-free envelopes

3) The survey acts as a shelf check of the manuscripts.

4) Although the manuscripts were catalogued by Mynors, some of the descriptions date from as early as the 1930s and many reflect Mynors’ own research interests, heavily biased toward the texts of western medieval books. The survey has helped to identify underdescribed manuscripts needing improved catalogue entries to serve the wider interests of students of codicology and the history of the book. Areas particularly needing improvement are descriptions of historic bindings, details of illumination and book decoration, early modern manuscripts and non-western manuscripts.

5) Electronic records make it easy to flag the manuscripts’ physical condition to potential users on our website, so it is clear in advance which need (extra) special care in handling and which (few) will not be produced to researchers in their present condition. This will inform staff handling and manuscript-specific instructions on handling to readers. Better handling will improve long term preservation by decreasing the likelihood of further damage.

6) Similarly, exhibition/loan requests can receive quick and detailed responses about the suitability of specific mss for display and particular considerations needed. Where necessary, treatments can be prioritised or alternative candidates found. Staff will be able to balance the physical exposure of manuscripts across the collection rather than repeatedly displaying the same few well-known and regularly requested ‘treasures’. Increasing the breadth of manuscripts displayed will lead to institutional appreciation of the collection as a whole rather than a set of highlights with an anonymous hinterland of unknown quality.

7) Staff can easily find FAQ statistics e.g. largest, smallest, oldest, unusual characteristics, shared features, authors, texts, dates; these will be useful for reports, teaching, outreach, displays and online features.

8) Improved staff/institutional knowledge of the whole collection has already led to use of some of the less-frequently consulted (and formerly less valued) manuscripts for teaching and school outreach purposes.

More benefits and further uses of the survey are still emerging:

- Conservators are adapting database template for use in similar surveys with other colleges.

- a research-experienced volunteer is gaining curatorial experience and starting improvements to descriptions of codicological and decorative features to support teaching, research and exhibition requirements (see (4) above).

- an academic researcher has been provided with the most complete list available to date of all Balliol manuscripts within a date range containing illumination (in this case, decoration using pigments and metal e.g. gold leaf). The list derived for these criteria from the survey database is considerably longer than any comparable list yet in print.

A few survey numbers

- MSS surveyed: 497

- people involved: 9

- staff hours: ca. 240 (ca. 120 each Balliol and OCC)

- no. & % of mss in good condition: 211

- no. & % of mss in fair condition: 196 + 22 in ‘fair-to-good’ condition, indicating that some minor repairs would make the manuscript significantly safer to produce.

- no. & % of mss in poor condition: 38 + 24 in ‘fair-to-poor’ condition, usually meaning that one of the boards is detached but the MS is in otherwise fair condition

- no. & % of mss in unusable condition: 6

- largest MS: two answers: largest volume MS 228, dimensions 480x350x125 mm, vol 0.021 m3; and largest boards MS 174, dimensions 480x370x090 mm, vol 0.0159 m3 .

- smallest MS: MS 378, a book of prayers in Ethiopic, written on parchment with wooden boards and a nice example of Coptic binding. It measures 081x062x035 mm.

- oldest MS: MS 306, part of which is a 10th century copy of a text by Boethius

Have a look at our conservation survey series of posts for more details of our discoveries! Still more to come…

Q&A: Access to St Cross Church and Balliol’s special collections

I am often asked about the status of St Cross as a church, and about how members of Balliol College, the University of Oxford and the wider community can get access to the building and the collections housed in it. Here is a collection of those questions and answers.

Q: I walked past St Cross church yesterday and tried the door. It was locked. Churches should be open! Why isn’t St Cross open?

A: St Cross is no longer a parish church. It was decommissioned in 2008. In latter years at least, the door to St Cross was usually locked even while it was a parish church – visitors could borrow the key from the lodge at Holywell Manor, next door.

St Cross’ door is normally locked because it is now part of Balliol College’s library. Many people come by the church every day, and a good number try the door handle. It would be very disruptive to staff and researchers to have visitors walking in and out of a library reading room – and extremely draughty!

Q: So St Cross has been deconsecrated?

A: It has not been deconsecrated; the chancel and sanctuary furniture and arrangement are as they were. The font has been moved (with all the required permission of course) to the north side of the chancel step, under the Freeling memorial. The chancel is now a chapel of ease to the University Church of St Mary the Virgin, and occasional services are celebrated in the chancel by St Mary’s clergy or the Balliol chaplain.

If anyone can provide a link to a good clear explanation between the terms closed, redundant, decommissioned and deconsecrated regarding churches, please leave a comment below!

Q: Can I come to St Cross to see the historic parish records? Or records of burials in Holywell Cemetery?

A: All of St Cross’ parish records have been deposited and can be consulted by appointment at the Oxfordshire History Centre on Cowley Road; this is the repository for parish records in the Oxford diocese. Holywell Cemetery records are also there. Balliol does not have copies of these records at St Cross.

Q: St Cross is part of Balliol now, and hey, it has wifi! Why can’t members of Balliol come in when they want with their swipe cards, the way they can in other parts of the college? And if it’s part of the college library, can Balliol students use it as a reading room?

A: Several reasons – first, you try getting permission to mount swipe card or security tag kit on a grade I listed building! Second, those using the special collections have priority in this building, because they cannot consult copies anywhere else – there aren’t any. Then too, for obvious preservation reasons (bearing in mind that everything we have here is unique and irreplaceable, and it is all old and fragile, or will be one day) any special collections reading room has considerably stricter regulations than the college library does: food, water, gum and sweets are not permitted. Neither are outdoor coats or any bags at the table. Neither are pens – pencil only. [further details here and here]

All that said, of course students can come in and use any of the collections here for research. Making an appointment is pretty easy – it just requires a little forward planning. Aside from curriculum-related research, there are numerous opportunities for current and past members to visit St Cross and see the collections during special events throughout the year. (Students can request and help to plan said events, too!)

Q: It’s sad to see empty churches. I suppose St Cross is always empty now that it is not a parish church?

A: The building is definitely not standing empty these days! Balliol’s Special Collections Centre at St Cross is usually staffed Monday-Friday, and there are researchers using the collections here on most weekdays, as well as tour groups and individual visitors. All visitors need to make appointments except for advertised public open days, which are held on weekdays and at weekends. More than 1000 people visited St Cross in 2012.

Q: I suppose only members of Balliol can use the building now. Can’t the public get into St Cross church at all anymore?

A: Although it is now leased, maintained and occupied by Balliol College, St Cross has not been made permanently inaccessible to the general public. Anyone who is interested can make an appointment to tour the building, and anyone with a bona fide research question can make an appointment to consult Balliol’s special collections here. [contact]

The church is open to the public – in the sense of the door being open – at least once a month, for open days, public lectures, exhibitions and services. Please contact staff for the next dates. [contact]

Q: Why all this need for appointments? I’d rather just be able to turn up when I want.

A: Some larger (e.g. county) archive services are able to accommodate visitors without appointments, but most archives and special collections libraries with few staff require appointments, and even if they are not required, you are likely to get a better service if you arrange your visit in advance. There are several reasons why appointments are necessary for all visitors; the intention is to accommodate as many visitors as possible as well as possible, not to keep them away.

– St Cross is a busy place these days, and we need to make sure that users can all make the most of their visits – for instance, we tend to avoid scheduling tour groups on days when individual researchers will be working, and vice versa.

– The number of researchers who can be accommodated on any one day is fairly small, restricted by the space available; by arranging your visit in advance, you will be sure of a seat and can plan your time.

– Staff need to be able to plan their work schedules, and may need to arrange ahead of time for extra invigilation cover for researchers.

– There are times when the Centre is closed or can only provide support for internal College enquiries.

– Visitors often come from far away, and we need to make sure they – you – are able to make the most of their, or your, limited time at St Cross.

– If you are making a visit for research, pre-ordered items will be ready for you when you arrive, maximising your research time. In addition, staff will be able to advise you on other relevant collections, provide finding aids in advance in most cases, and notify you of any materials which are not available for consultation.

Many things have changed at St Cross over the last several years – we hope that most of them have changed for the better!

not least the state of the building itself – must post some new photos of the interior, restored and in use. Coming soon!

horns of the dilemma

Access and preservation – pillars of the profession, or, the archivist’s Scilla and Charybdis

I detest being pushed into the role of curmudgeonly dragon, so I wish people would not request to ‘glance through’ (e.g.) 19th century literary papers because they like the subject’s poetry. This is just not a good enough reason to ask to handle fragile, light-sensitive documents that are 150 years old. Use of archives is normally the final step of primary research on a particular thesis (research question), after thorough investigation of secondary and published sources. And I will say so, because my first duty is to the college and the preservation of its collections – otherwise there will soon be nothing left! But thank goodness for digitisation and the huge increase in access it makes possible. I am as committed to increasing access to the information within the collections as I am to physical preservation of the originals.

While the corollary of increased access via digitisation is increased preservation of the original, its flip side is decreased access to the original. I do not produce manuscripts that have been digitised except for codicological queries that truly cannot be answered by consulting the facsimile. There is something special about direct contact with an ancient codex, but the fact is that every exposure to light, fluctuations in temperature and humidity and handling, however careful, inevitably causes cumulative and (at least in the case of light) irreversible damage to paper and parchment.

Access and preservation often pull in opposite directions, and the needs of the reader and those of the archives can appear to be in conflict. But archivists have to hold these two poles in some kind of balance, because without preservation there will soon be no access, and without access – and I emphasise that in most cases the important thing is access not necessarily to the physical objects but to the information they contain – preservation would be pointless.