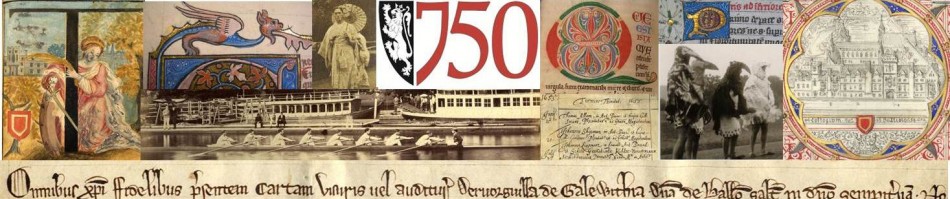

Digital images of medieval manuscripts

What an encouraging tweet exchange this morning:

Daniel Wakelin @DanielWakelin1

@balliolarchives Balliol’s energetic use of Flickr was one of our inspirations to experiment with this medium for #DIYdigitization @BDLSS.

Balliol Archivist @balliolarchives

@DanielWakelin1 @BDLSS WOW. That has made my day.

Daniel Wakelin @DanielWakelin1

@balliolarchives Truly. Your ‘roll up my sleeves and get on with it’ process of #DIYdigitization. @BDLSS may want to interview you about it.

Balliol Archivist @balliolarchives

@DanielWakelin1 @BDLSS Always happy to talk about opening access to manuscripts 😀

YES. Big grants are great but one person with one camera can get a lot done even in an hour or two here and there (my photography has to fit in along with all the rest of the job) and make a real difference – and, it seems, not just to the individual researchers who request particular images but to institutional policy and approaches to openness of access. Lovely to find my hunch (gut feeling/considered professional opinion) is turning out to be correct. Keep on clicking!

Q&A: the Register

When using the Balliol College Register images online, I am confused by sets of usually 3 initials in parentheses, following the Balliol years in the education section of many entries. What do they mean?

Initials in parentheses are those of that student’s Balliol tutor(s). You can find a list of tutors’ initials just before the Index, and then use the Index to find that tutor’s own entry.

College Register 2nd edition 1833-1933

College Register 3rd edition 1900-1950

a query

How can I access a copy of George F. Kennan’s Reith Lecture of 1957? Many thanks.

Thank you for your enquiry re Reith lectures of GF Kennan (George Eastman Professor at Balliol College 1957/8). If you Google ‘kennan reith lectures’ you will see that the BBC has made audio and full transcripts available online.

Family History enquiries

Looking for information about an individual who may have been a member of Balliol College? Here’s how:

(1) Balliol biographical research resources – see also the University Archives’ helpful links to several of the same sources.

(2) AE Emden, A Biographical Register of the University of Oxford to AD 1500 (3 vols, 1957) and a supplementary volume 1501 to 1540 (1974). (Print resource only)

(3) Joseph Foster, Alumni Oxonienses 1514-1700 and 1700-1886

(4) Oxford University Archives

(5) Oxford University Calendar and the Oxford University Degrees Office

(6) Oxford Archivists’ Consortium (OAC) – contact details for all college archives and other local resources

Open Days this weekend!

Balliol College’s Historic Collections Centre at St Cross Church, Holywell

will be open to the public as part of Oxfordshire Historic Churches Trust Ride & Stride

Saturday 13 September 2014 12-4 pm

and

Oxford Open Doors (Oxford Preservation Trust in partnership with the University of Oxford)

Saturday & Sunday 13-14 September, 12-4pm both days

There will be an exhibition in the church about the Balliol Boys’ Club and the First World War – more information on p.31

These events are of course FREE!

Ride & Stride participants, please note that the church will not be open during the whole official event time of 10am – 6pm – please come and visit us between 12-4pm.

Directions: http://archives.balliol.ox.ac.uk/Services/visit.asp#f

reading closely

An interesting enquiry from last year, demonstrating that the internet is a brilliant research tool, but that like any source it needs careful interpretation, and that not all immediately available information is correct or complete.

An interesting enquiry from last year, demonstrating that the internet is a brilliant research tool, but that like any source it needs careful interpretation, and that not all immediately available information is correct or complete.

The enquirer requests information on William Hussey 1867-1939, son of Thomas Hussey of Kensington, stating that the images sent with the enquiry, of a Ladies’ Challenge Cup medal, clearly show that WH rowed for Balliol when they won that particular race in 1891.

The enquirer has probably searched for something like ‘ladies challenge cup 1891’ and found the Wikipedia page http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ladies’_Challenge_Plate for the Henley Regatta’s Ladies’ Challenge Plate race, won by a Balliol crew in 1891, and concluded that Hussey must have been part of this crew.

In fact the medal shows nothing of the kind, and a closer look reveals quite a different story.

First I checked whether William Hussey had indeed been a member of Balliol – the college registers are not 100% infallible, but they are pretty good. No result, so back to the medal for other clues. A little more scratching around online revealed several things that didn’t add up to support the Henley & Balliol assumption:

- Date: Henley is always held over the first weekend in July, but 1 July 1891 was a Wednesday. (thanks Time and Date!)

- Race name: the Ladies’ Challenge Plate race at Henley has never been known as the Ladies’ Challenge Cup – it is the only Henley trophy that isn’t the Something Cup.

- Winner name: the LCP is an Eights race, not an individual one, so even if each member of the winning Eight had a commemorative medal, it would not be inscribed ‘won by [any single name]’. Cf. Henley commemorative medals at http://www.bonhams.com/auctions/18783/lot/59/, a particularly nice find after searching for images of the LCP medals for visual comparison.

- Double-checking with another source – even supposing everything else was somehow wrong, we have a photograph of the Balliol Eight that did win the LCP in 1891; the rowers were: Rofe, Rawstone, Darbishire, Mountmorres, Fielding, T Rogers, Farmer, F Rogers, cox Craig-Sellar. Not surprisingly, no Hussey.

So if it was not at all connected with the Henley Royal Regatta or Balliol’s win there in 1891, what is this medal? Balliol-based evidence stops here, but ‘we have no further information about this’ seemed a bit abrupt when most of what I had already found out was from non-Balliol sources anyway. Besides, by this time I wanted an answer to the puzzle, if I could find one!

Look at it again – the intertwined letters on the medal look like T C D, in a distinctively Irish style, and Trinity College Dublin’s Regatta does include a Ladies’ Challenge Cup race. But to check up further, one might try looking at the club’s own site: http://www.tcdlife.ie/clubs/boat/archive.php. The answer is probably in Raymond Blake’s book, In Black and White: A History of Rowing at Trinity

College Dublin. My research ends here; I can’t spend any more time on this enquiry, and the answer won’t add to knowledge of the Balliol archives.

And there are still questions: why should the medal read TCD when TCD’s boat club has been known as the Dublin University Boat Club since 1847? Is the DUBC (TCD) Ladies’ Challenge Cup race rowed by singles or eights? Is there any evidence at all that this is a rowing medal?

It’s rare that answers to archival enquiries are either complete or absolute – often, the best we can hope for is to add another interesting piece to the puzzle, or point in another direction.

Q&A: time, gentlemen, please

Q: Another good question from @RussWrites to #AskACurator: Do you get annoyed if people don’t want to leave the museum [or archive, or library] on time at the end of the day or is it a compliment?

A: I’m always glad to hear that researchers have had a good day, but it really is important to plan the day’s work, keep an eye on the time, and pack up promptly when advertised reader hours are coming to an end. I hate having to hurry people or sound like a jobsworth, but I’m not paid to stay late and I can’t just take time tomorrow or some other day, because other researchers will be turning up on time. I can’t very well take a hint from this post’s title and invest in a handbell – ridiculous for a room occupied by only a few people.

The fact is, many archives, and small and/or specialist libraries, only have one or perhaps two (or one and a half) members of staff – who are trying to do a full day’s work of their own as well as invigilating and assisting researchers. There’s no leeway; there’s no faceless institutional system that automatically takes care of these things. If a researcher stays ‘just another fifteen minutes’ to finish what he or she is doing, somebody is probably going to miss a train. Be aware that staff hours are often longer at both ends of the day than the advertised reader hours. Especially in small repositories, it comes down to individual courtesy.

P.S. Any researcher hoping for an enthusiastic audience is advised to avoid starting a detailed description of the day’s discoveries just before closing time! Archivists tend to love their work, and many put in unpaid hours to assist researchers and get the job done as they want it to be – but they don’t live there.

I shall finish what seems a rather negative post by saying that most researchers in person are efficient, courteous, interesting and a pleasure to work with!

P.P.S. Best response from the Twitter discussion from @Rupriikki: ‘Nice one! We are of course very flattered! (…And politely trying to go home at the same time.) They can revisit!’

Q&A: digitisation

Q: Responding to a good query from @ojleaf for the #AskACurator conversation on Twitter: If you are digitising precious documents, does it frustrate you if people still want to handle the original?

A: No.

See previous post about the constant balance between preservation and access.

First, for ‘precious’ read ‘OLD.’ It’s hard to remember that a medieval manuscript in good condition, with its illustrations still bright and its parchment still smooth, is at least FIVE HUNDRED years old and may be much older. Parchment is very tough stuff, and ancient books can be enormous and very heavy. It is hard to remember that such physically formidable objects really are fragile. That doesn’t necessarily mean that pages will tear easily, or even that the books will break into bits if you drop them. They are physically vulnerable, especially the ink/paint and bindings, but less obviously, they are also chemically vulnerable – to our warm breath, to the oils on our hands, to the light we read by.

‘Because I want to feel closer to the past’ is a completely understandable reason for someone to request direct access to, say, a medieval manuscript book, but not a valid one on its own. I sympathise (all very well for me, I have direct contact with these things every day – at least in theory) but in principle, what seems more important to me (and there is always a balance to be struck between the two) is access to information rather than access to objects. HOWEVER! if a researcher is able to demonstrate that he or she needs information from the original document that is not obtainable from a facsimile, then of course I’ll produce the original. This happens quite often. Using facsimiles, especially good quality digital images, is a great way for most researchers to get most of the information they need without having to expose the original to the wear ( = damage) of repeated handling and changes in light, temperature and humidity.

Eventually a researcher may well have to come and check the original manuscript in person, but advance preparation and familiarity with the contents, layout and visual characteristics of the manuscripts – and potential problems – will make the time spent with the originals that much more productive. Thanks to digital images, that time may be reduced from days or weeks to a matter of hours. In practical terms, having access to decent digital images, preferably in advance of a visit to see the original (but better afterwards than never) will usually mean:

- ability to

- view images at much-magnified resolution, i.e. larger than the original

- manipulate images to improve colour, contrast etc – so many manuscripts are written in brown on brown

- view pages in any order, any number of times

- reconstitute original order in cases of misbinding

- juxtapose images of pages which are not physically facing each other

- view more than one opening at a time

- use images in illustrations for discussion, publications presentation, teaching etc

- sit in comfort at home, at own computer, in own chair, with own mug

- reduction of

- number of research trips

- travel time

- travel and accommodation costs

- time spent in archives, where (with the best will in the world) light may be low, temperatures unpleasant, access awkward, chairs uncomfortable, and pens, water, cough sweets and tea not allowed!

We hope that’s an improvement for everyone. And we do have exhibitions of all sorts of items from the special collections – even if visitors are not able to leaf through a 400-year-old Aldine imprint, they can get pretty close to a good number of Exciting Old Things and hopefully find some interesting information about them in the captions or catalogue. Maybe some will be inspired to start their own research projects…

Q&A: digitisation

I was recently asked: ‘I noticed that quite a bit of material from your archives has been digitized, and that you have put it to fine use by widening access to the collection on the website and through online exhibitions. I wondered how you are going about digitizing the items – are you working in-house, or are you using an external organization to do it, or a mixture of both? Please could you tell me how this is being financed, and if you are aiming to digitize the whole archive or just a part?’ This isn’t the first time I’ve been asked about my digitization programme at Balliol, and it prompted a bit of an essay on how I do things now and how that has changed since I began in October 2010. So here’s is an update to what I was thinking then.

I do the digitising myself – I have an excellent A3 scanner and a serviceable but outdated camera which I’m about to replace. I allocate a few hours a week to scanning & photography so that it progresses regularly, if not quickly, but I am posting about 2000 images a month these days.

The occasional exception is when someone wants to photograph an entire manuscript or series for their own research; in such cases I ask for copies of the images and permission to publish them online and make them freely available to other researchers, with credit to the photographer of course. So far the few people I’ve asked have been very happy to do this, since they have had free access and permission to photograph. (Sometimes their images are not as good as mine, so then I don’t bother!)

There are also numerous documents in the collections that are just too big for me to photograph – eventually, if and when they are asked for, we will have to think about having someone in to photograph them systematically. So far the multiple photos of each that I or the researcher have been able to do has sufficed.

For now at least, I have decided against a systematic digitisation of our microfilms of the medieval manuscripts. This would involve a lot of time and effort to fund and arrange, the images would all be black and white, and of variable quality, and there are knotty questions of copyright as well. Some of the MSS were only partly microfilmed, and none has more than a single full-page perpendicular view for each page – no closeups or angles to get closer to initials, erasures, annotations, marginalia or tight gutters, so there would still be considerable photography to do anyway. Also, see below.

Why don’t you apply for a grant and have a professional photographer do more than you can do yourself?

So far, I’m able to fulfil reprographics orders in a pretty timely manner and to a standard that satisfies enquirers. Aside from cost and time management for individual orders, because I can respond individually and fit them in around my other tasks, the great advantage of doing the digitisation myself is that I am getting to know the collections extremely well. If we had an outside photographer do it, all that direct encounter with each page would go to someone with no real interest in the collections, what a waste. This way, I’m checking in a lot of detail for physical condition, learning to recognise individuals’ handwriting, discovering/replacing missing or misplaced items, prioritising items that need conservation or repackaging, noticing particularly visually attractive bits for later use in exhibitions and so on, and not least ensuring that items are properly numbered – which many are not!

What is the cost?

Because I work reprographics orders into my regular work schedule, there is no extra cost, except the £50 or so fee every 2 years for our unlimited Flickr account.

Because I work reprographics orders into my regular work schedule, there is no extra cost, except the £50 or so fee every 2 years for our unlimited Flickr account.

Do you charge for access?

I always mention that donations are welcome, but in general I do not charge for reprographics. Most of the requests are from within academia, and I think HE institutions have a responsibility to be helpful and cooperative with each other and with the public, particularly when it comes to access to unique items. On the one hand, I know that special collections are extremely expensive to maintain, and often have to sing for their supper, but on the other I know how frustrating it is to be denied the chance to take one’s own photographs and then to be charged the earth for a few images. Institutions like ours, whose own members may need such cooperation from other collections and their curators, should probably err on the side of the angels er scholars! Most of the other requests for images are for private individuals’ family history research purposes, and since many of those enquirers would otherwise have no contact with Balliol or Oxford, I think it’s good for the relationship between college, university and the wider public to be helpful in this way. Family history is usually very meaningful to researchers, and they remember and appreciate prompt and helpful assistance.

Balliol College reserves the right to charge for permission to publish its images, but may waive this for academic publications.

Are you planning to digitise all the collections or just parts? What are your priorities and how do you determine the order of things to be done next?

Most of the series I’ve put online don’t start with no.1. All the reprographics I do now are in response to specific requests from enquirers, and I don’t seriously intend, or at least expect, to digitize All The Things. Although 40,000 images sounds like a lot, and there’s loads to browse online, I’ve barely begun to scratch the surface; most collections aren’t even represented online – yet… This way, everything I post online I know is of immediate interest to at least one real person – if we did everything starting from A.1, probably most of it would sit there untouched. For the efficiency of my work and for preservation of the originals, digital photography is marvellous, enabling me to make every photo count more than once rather than having to photocopy things repeatedly over the years.

On the other hand, if someone asks for images of one text occupying only part of a medieval book, I will normally photograph the whole thing; or if the request is for a few letters from a file, I will scan the whole file. It’s more efficient in the long run, as a whole is more likely to be relevant to other future searchers than a small part.

What about copyright?

I probably should mark my own photos of the gardens, but I don’t think anybody will be nicking them for a book and making millions with it. As for the images of archives and manuscripts, of course I am careful to avoid publishing anything whose copyright I know to be owned by another individual or institution, but for older material that belongs to Balliol, I’m with the British Library on this one. I think as much as possible should be as available online as possible, for reasons of both access and preservation.

I probably should mark my own photos of the gardens, but I don’t think anybody will be nicking them for a book and making millions with it. As for the images of archives and manuscripts, of course I am careful to avoid publishing anything whose copyright I know to be owned by another individual or institution, but for older material that belongs to Balliol, I’m with the British Library on this one. I think as much as possible should be as available online as possible, for reasons of both access and preservation.

We do have some collections whose copyright is held by an external person or body, and in some of those cases I am permitted to provide a few images (not whole works) for researchers’ private use, but cannot put images online or permit researchers to take their own photos.

How do you make images available?

Now that other online media are available, I am reducing image use on the archives website, to use it as a base for highly structured, mostly text-based pages such as collection catalogues, how-tos, research guides etc, as this information needs to be well organised and logically navigable. These days I am using this blog for mini-exhibitions discussing single themes and one image, or a few at a time.

Flickr is a good image repository for reference, not so much for exhibitions – I’ve written about that at https://balliolarchivist.wordpress.com/2013/05/01/thing-17/

I expect I will have rethought the digitisation process again in a couple of years’ time!

Q&A access to college collections and using archives for historical research

Q: I need to use primary sources for my essay/dissertation. Are there interesting sources in College archives? Where do I start?

A: The Lonsdale Curator is always glad to hear from students and tutors and to discuss potential sources in the College archives and elsewhere. At the moment I have students working on club and society records, the Swinburne Papers, the Jowett Papers and the Urquhart Papers. While college libraries are normally open only to members of that college, college archives and manuscript collections are open to anyone with a bona fide research question that requires access to the original source material. Primary sources are very exciting, but they are not always the most efficient way to get distilled information – after all, the reason or method in which the information was originally gathered and recorded, whether 25 years or a century or more ago, may well have had nothing to do with the kinds of information you want to get out of that record, or the way we think about it now. So make sure you exhaust secondary sources first – someone may have done a lot of the legwork for you!

Here’s something I prepared earlier about using archives for historical research:

These readings are recommended for anyone planning any type of research project that will require consultation of archival or manuscript material.

- from the Institute for Historical Research – article

- from the University of London Research Library Services – article

- Archival Research Techniques and Skills – student portal

- University of Nottingham: Document Skills – Introduction

A few notes:

- Plan ahead.

- Many archives are not open full time and have very limited space for researchers; it may take some time for the archivist to answer your enquiry, or to get a seat, so plan your visit in advance.

- Make sure you need to see the original material (see below), and if you do, that you are as prepared as possible.

- Do your secondary reading first, and find out which of your primary sources have been published, edited, calendared or indexed.

- You will need that information in order to engage fully with the primary sources and make the most of your valuable research time.

- Secondary sources often cite relevant primary sources and their locations.

- Published sources may be available to you more easily and with less travel than original ones.

- You will be better equipped to make enquiries of and ask for assistance from archivists and manuscript librarians.

- The professionals you deal with will be able to tell whether or not you are well prepared, and you are likely to get more detailed responses if your enquiries are well informed. If it’s clear you haven’t read basic printed sources, they are quite likely to send you away to do that first. If you ask for primary sources which have been published, you will be given the published version.

- Use the online archive networks.

- There is an ever-increasing amount of information online about archives, from general national databases to subject-specific portals. A few of the networks are listed here.

- Ask for help.

- You are not expected to know everything about where to find primary sources. It’s more complicated and less systematic than identifying published sources, and archivists and curators are specialists in this kind of lateral thinking. (But do your homework first!)

AskArchivists Q&A

The College Archivist is always glad to hear from students interested in finding out about work experience, formal training or careers in archives, records management or conservation.

Read more at:

The Archives & Records Association, formerly The Society of Archivists (UK)

How to contact Oxford college archives

If you are doing family history research or for any other reason want to find biographical information about a former member of an Oxford college who has been deceased for more than a year or so, you should get in touch with the archivist.

College alumni or development offices deal with living alumni. College offices / senior tutors / registrars deal with current students. Contacting them about deceased members of college will result in an email round-robin and a delay in response.

If you are not sure which college your research subject belonged to, check these sources according to period:

- pre-1540: Emden, AB.A Biographical Register of the University of Oxford to AD1500, 1957-9, and A Biographical Register of the University of Oxford AD1501 to 1540, 1974. Not available online.

- 1500 – 1714: earlier volumes of Foster’s Alumni Oxonienses

- 1715 – 1886: later volumes of Foster’s Alumni Oxonienses – links here

- 1880 – 1892: Foster’s Oxford Men and their Colleges

- pre-1932: Oxford University Archives

- post-1932: Oxford University Degrees Office

If you do know, or once you find out, which college your research subject belonged to, contact that college’s archivist for further information. Contact details for all colleges that have an archivist are available at http://www.oxfordarchives.org.uk/college%20archives.htm

If you have a query that may apply to several or all colleges, you can save a lot of cutting and pasting of addresses by sending it to the college archivists’ mailing list at oac[at]chch.ox.ac.uk.

International Archives Day 2012!

I’ll be celebrating International Archives Day (9 June) by participating in #archday12 on Twitter, organised by @AskArchivists. The day itself is a Saturday, so like many archivists around the world I’ll be taking questions and posting content (links on twitter to content here on the blog) on Friday 8 and Monday 11 June.

It’s an opportunity to ask all kinds of questions about archives, archivists and research using all kinds of original source material, from medieval manuscripts to early modern maps to photographs and film. Come and join in!

If you are not on Twitter, you can also ask questions for this event via the Facebook page or by the usual email. To see questions answered during last year’s #AskArchivists event, click the tag.

http://twitter.com/#!/balliolarchives.

http://askarchivists.wordpress.com/

AskArchivists Q&A 3

Another couple of musings on questions tweeted during Ask Archivists Day:

Q: What is a typical day as an archivist like?

I’ve never yet had the same day twice, and I like that. A typical day is constantly interrupted, which can be frustrating (and inefficient), but requires short-term flexibility and long-term focus. A good day is one in which you can start AND finish something. Or at least finish something. Most of my days at the moment consist of some or all of the following:

- packing archives on the main site

- unpacking on the new site

- answering enquiries, possibly a bit more briefly than usual

- labelling boxes

- updating the locations database as more boxes are shelved

- adjusting lots of metal shelves in the new repository to maximise space use efficiency, since so many of our things are not standard sizes

- letting maintenance people in and out, and trying to decipher all the tech-speak to find out what they are actually doing, and what I may need to know about its inner workings later

- telling tourists that St Cross is not a parish church anymore, but rather a college building, and so they are not allowed to wander round, but that if they have a research question, including about the memorials in the church, they are welcome by appointment from October, and that the church will be open to the public for Oxford Open Doors on the second weekend in September (subtle plug there)

Ask me again in three months and there will be no more packing and upacking, but quite a lot more fetching and replacing of archives from the repositories, invigilating of researchers and (if I’m lucky) cataloguing on the list! A particularly good day ends with a group of college archivists meeting in the pub.

Q: What draws most of us to the profession?

I’d be curious to see others’ response to this question; I suspect that few paths to a career in archives are without twists and turns. I came at it sideways from a higher research degree in Medieval Studies, where I enjoyed learning medieval Latin and palaeography immensely. I love having a job in which such apparently arcane skills are of daily practical use, and I get to read, use, photograph and write about medieval manuscripts much more than most academics ever do, even though most of that work consists of contributions to or facilitation of someone else’s research. It’s always a challenge – you learn the standards and formulae, and you need those systems and frameworks to make any sense of archives, but they never apply in quite the same way twice. And one corner of my soul is forever a systems geek, so I have a certain guilty pleasure (very strictly limited) in records management theory. Despite the delight in systems, I’m not a naturally tidy person, so I appreciate being able to detect and restore order to a collection and describe it so that it becomes orderly, comprehensible and useful (and even interesting!) rather than just a frustrating box of messy STUFF. And – well, medieval Latin, 14th century handwriting… nowadays these are in effect secret codes, and being a codebreaker is very cool.

More AskArchivists Q&A

Sorry for radio silence lately – I haven’t been at my desk much, between packing, moving, unpacking and shelving archives and manuscripts. We have started moving the medieval manuscripts, the last main category of collections to be shifted, and are about 30% through those. Still to come are large numbers of cumbersome 19th century ledgers from the archives – heavy and awkward to move, and very numerous. The move is on track but will still take the rest of the summer, and our target opening date of 1 October (Monday 3 October in effect) stands.

I am not doing any interesting fossicking about in the records these days, but here are some more responses to Ask Archivists Day queries.

I can’t give credit where it is due for all these questions as I’m frankly totally confused about where they originate with all the retweets and so on, but they are all excellent and I hope their authors find these answers and find them interesting! Thanks to the Bod @bodleianlibs for collating their Q&As – I tried scanning the Twapper Keeper (who thinks up these things??) but started to go cross-eyed, and Bod did a great job of smoothing it all out into a readable list.

Q: What kind of building is your archive in?

A: The college archives used to be housed partly in the Library and mostly under the stairs to the Hall, in Balliol’s main campus on Broad Street. They were all consulted in the Library, which meant taking material outside and down the quad every time anyone wanted them. The manuscripts were all in the Library. Other special collections were housed in half a dozen other places (mostly below ground) dotted around college. None of the repository spaces was environmentally controlled. However, big changes have happened recently, and all of Balliol’s archives and manuscripts collections are all currently being moved to new premises in St Cross Church, Holywell, which has been converted for use as the college’s historic collections centre. At last we will be able to provide proper housing for the collections and a good research environment for readers! More about that project here. The collections are closed to enquirers in person during the move; we plan to open to researchers in October 2011.

Q: Why isn’t a library an archive?

A: Strictly speaking, a library contains printed books while an archive holds manuscript items and collections of papers. The ways in which these categories of written material are collected, arranged, described and used are quite different. In practice, however, many libraries also hold manuscript books and archival collections, and many archives have collections of printed books (usually as research reference sources, but sometimes as part of an individual’s or organisation’s archive). The line between librarians and archivists is an easier one to draw as they have different approaches to their types of collections; professional training in these two fields is distinct. Here’s a useful summary of the basic difference from Library & Archives Canada and I recommend the rest of this useful introduction to archives and archival research to anyone using primary sources.

Q: How many kilometers of shelves do you have in your depots? And are they all used?

A: There are about 1500m of shelving in the new repository at St Cross. I won’t be absolutely sure until all the collections have been moved in, but I expect to have about 10% left for future growth in the archives and manuscripts collections. The repository for the early printed books will be completely full, but we do not expect any additions to that collection. This is not much room in a new repository for future expansion of the archives, but the tradeoff is much-increased space in the library in Balliol’s main Broad Street campus, which is urgently needed to support the teaching and learning of current students and Fellows.

Q: Any ideas how to befriend an archivist?

A: Do your homework before making an enquiry, honour your appointments and don’t ask to bring coffee or wet coats into the reading room 🙂

Q: What item is missing from your archive or collection that you would most want to obtain and why?

A: Balliol is the only one of the earliest foundations in Oxford not to have any of its medieval accounts anymore; our administrative records don’t survive from earlier than the 16th century. Why is it missing? I think this was probably the result of a bursarial clearout some time in the 17th or 18th century, since medieval records are not mentioned in any of our early archival lists. Why would I like to have them back? Medieval accounts are a fascinating snapshot of ordinary life, full of payments concerning not only teaching and learning, dons and students, but cooks, plumbers, roofers, carpenters, laundresses and the other myriad people who made (and make) the place work. I am pretty sure Balliol’s medieval accounts really are gone, but it’s more pleasant to hope, very faintly, that some antiquarian scholar made off with them at some point, and that one day they may turn up. That kind of thing does happen occasionally, so one can dream…

Q: Do you have pics (on your website?) of archival exhibitions?

A: This question might mean do we have pictures of exhibitions (how the exhibitions were laid out) or of exhibits (the things themselves). I’ll assume it means the latter; yes, here.

Q: How long have you used Twitter and do you think it’s successful?

A: I started tweeting in May 2011, 35 tweets so far. My tweets also show up on the Balliol Archives & Manuscripts facebook page. Hard to know exactly what ‘success’ means in tweeting terms. My aims are to make what I do each day a little more visible, to increase awareness and use of our web resources (hopefully some of that use will give rise to enquiries and visits as well, but it may also help to answer some questions outright), to make contacts that allow me to share useful information about the wider world of archives and manuscripts with Balliol people and my other researchers, and as a lone archivist to stay connected to colleagues, ideas and developments from that wider world. So far so good – time will tell!

Q: What are your top priorities currently when it comes to archiving? Which records are most important?

A: My top priority at the moment is to move all the collections into St Cross and have systems in place in time to open for researchers on 1 October. (And can I say I don’t like the word archiving.) The intention is to have no records in the archives which are not important, of course, but then all sorts of records can become important later in their archival history for reasons that could not have been dreamt of earlier on. But institutionally speaking, the ‘first grab’ items would be College Meeting minutes and the ancient statutes and other foundation documents. Cases could also be made for the medieval manuscripts and some of the modern personal papers collections – this can be a highly subjective question!

Q: How many archives are also on Facebook? Please post links to your Facebook pages!

A: https://www.facebook.com/pages/Balliol-College-Archives-and-Manuscripts/123305954394903

#AskArchivists Day

Today is Ask Archivists Day! I’m not in the office this week, so I won’t be answering any questions today, but please send them anyway and I’ll gradually post answers here. In the meantime, here are the Balliol answers to a few sample popular questions posted on the Ask Archivists blog:

What is your oldest record?

– A charter regarding a grant of the Church of St. Lawrence-Jewry, London, with rents etc., from Robert, Abbot of St. Sauve, Montreuil, to John de St. Lawrence, etc. ca.1200

Are your records online? or will they be?

– Some are, but online records are not much use without good cataloguing and indexing. The amount of information on our website is growing all the time:

- summary catalogue of the administrative archives

- introduction and catalogue of the medieval manuscripts

- modern personal papers catalogues

- images of a number of documents from all of the above categories

If I come to your archives, do I have to pay?

– No. We do not charge either for access in person or for answering enquiries. We do, however, appreciate and encourage donations.

Do you have photos of my home town?

– Most of the photographs we have are of Balliol College itself. We have very few of other places. A gazetteer of places with different kinds of association with Balliol College is on our website at http://archives.balliol.ox.ac.uk/History/gazetteer.asp – we do not have photographs of most of these places.

How many kilometres of shelves do you have?

– about 1500 metres of shelving or 1.5 km.

Can I find my ancestors at the archives?

– Only if said ancestors were members of Balliol College. Our web page on ‘Tracing a Balliol Man’ has more details about the kinds of information we do and don’t have about individual former students.

What does it take to become an archivist?

- a good degree in something. It does not have to be in history. Mine isn’t.

- some practical experience of working in an archive, probably volunteering for a few weeks or the equivalent

- admission to a UK professional course in archives administration usually requires a year’s graduate trainee experience in an archive, or the equivalent

- a willingness to move for work – many jobs for recently qualified archivists are short term contracts

- ideally, a combination of intellectual inquisitiveness, secretarial meticulousness, ability to work as part of a team and alone, excellent communication skills (both in writing and in person) and in many cases enough physical fitness to go up and down ladders, carry boxes, navigate awkward stairways and impossibly narrow corridors, and climb around in attics and basements.

Which document is the most precious in your collection?

– That depends how you define precious. We don’t have any manuscripts of Chaucer, copies of Magna Carta or the Mappa Mundi, gorgeously illustrated medieval liturgical books, First Folio Shakespeares or even a first edition of Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations, and he was a Balliol man. But for someone who is looking for information about their great-grandfather, a rowing photo from the 1880s may be very precious indeed. You can see some of our medieval manuscripts at Early Images Oxford and a growing number of our varied kinds of treasures online at our Flickr page.

Oh, and one other thing about Ask Archivists Day: if you have questions about a particular archive, you don’t have to wait to ask until 9 June or any particular day. We’re not waiting for your questions – we’re answering them all the time, and working to make our records better available to more researchers. So you can ask more questions! and find more of the answers. That’s what we’re here for.

You can follow @AskArchivists on Twitter.