Balliol ARCH C. 1. 9 #mss2017

Guest post by Sian Witherden

Balliol College Library has one copy of the Rudimentum Novitiorum (‘Handbook for Novices’), an encyclopaedia of world history whose author remains anonymous. This book was printed on paper in Lübeck by Lucas Brandis on the 5th of August 1475. The volume is quite large at 380 x 290 mm, and it is still in the original stamped leather binding. Other copies from the same print run are held in libraries across the globe, including Berlin, Copenhagen, Moscow, Paris, Prague, Princeton, Vienna, and Zürich. Each of these copies has its own unique history, but what is perhaps most remarkable about the Balliol copy is the way it has been dismembered by a later reader (or perhaps readers). Many of the woodcut prints in this volume have been cut out, though there seems to be no obvious reason why certain images were selected for excision and not others. Perhaps the reader wanted to keep these particular ones for a scrapbook or put them to use in another volume. Unfortunately, leaves are also missing from both the front and back of the book.

Another reader was evidently so dismayed by the extent of the losses that he felt impelled to make a comment in the margins: “Is it not a great shame to the scholars of Balliol College to suffer such a choice book as this is to be thus defaced?”[1] There is of course a distinct irony to this, as the annotator takes issue with the defacement of the volume while simultaneously adding his own blemishes to the same book.

In the sixteenth century, the book was evidently owned by John Wicham, whose name appears twice on the outer cover along with the year 1584. Curiously, the book is incorrectly identified as the Opus Historicum of Guillerinus de Conchis both on the spine and within a flyleaf note written in “a late sixteenth or seventeenth century hand,” according to Dennis E. Rhodes. The Rudimentum Novitiorum has no connection with Guillerinus de Conchis.

* * *

For further reading on this book, see Dennis E. Rhodes, A Catalogue of Incunabula in all the Libraries of Oxford University outside the Bodleian (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1982), 296–7.

[1] Abbreviations have been silently expanded and orthography has been modernized.

– Sian Witherden, September 2017. Follow Sian’s tweets @sian_witherden

light #mss2017

Light exposure (lux, UV, heat) is always a concern during exhibitions. How much light does St Cross get, and how can ancient manuscripts be protected while also being made accessible to visitors?

First, limiting exposure. Exhibitions of original material run for 3 months maximum. Pages exposed are changed regularly where that’s practical for the topic of the exhibition. Depending on their condition, books are closed whenever open hours are not planned for a few days in a row. Thanks to the condition survey and research following from it, I’m developing a ‘rota’ of manuscripts that can be produced as examples of various features, rather than getting out the old favourites every time.

The interior of St Cross, including the book cases used for exhibitions, does receive a surprising amount of natural as well as artificial light. The clerestory windows on the south side, although they are small and high, allow a lot of light for much of the day on the shelves on the north side of the nave. The above photo is taken with no artificial lighting on at all, around midday in early September. It is clear to see how much more direct sun shines on the upper than the lower shelves.

Thanks to the deep shelving and even deeper pelmets on top of the cases, the back of any shelf receives much less direct sunlight than the front. But manuscripts on display need to be as visible as possible – at the front of the case.

Also at the front of the case are these very bright and undimmable LED lights down both sides – they provide all the ambient light to the working area of the reading room as well as illuminating the objects on the shelves. It would be complicated and expensive to install temporary, movable conservation-standard low-level lighting in all these cases. The LEDs emit practically no heat or UV at all, and their intensity decreases dramatically a few inches away. But they are still pretty bright.

Also at the front of the case are these very bright and undimmable LED lights down both sides – they provide all the ambient light to the working area of the reading room as well as illuminating the objects on the shelves. It would be complicated and expensive to install temporary, movable conservation-standard low-level lighting in all these cases. The LEDs emit practically no heat or UV at all, and their intensity decreases dramatically a few inches away. But they are still pretty bright.

There is a simple and effective, if not ideal, solution: open manuscripts (or indeed closed books, as bindings suffer from sunning as well) are covered with a (new) acid free folder, or similar conservation-quality light card cut to fit, outside of exhibition open hours. This blocks pretty much all the light from sunshine and artificial lighting.

The free-standing exhibition cases are fitted with heavy card covers, which are also in place outside exhibition open hours. These are easier to put on and remove than their usual full-length wooden covers.

The free-standing exhibition cases are fitted with heavy card covers, which are also in place outside exhibition open hours. These are easier to put on and remove than their usual full-length wooden covers.

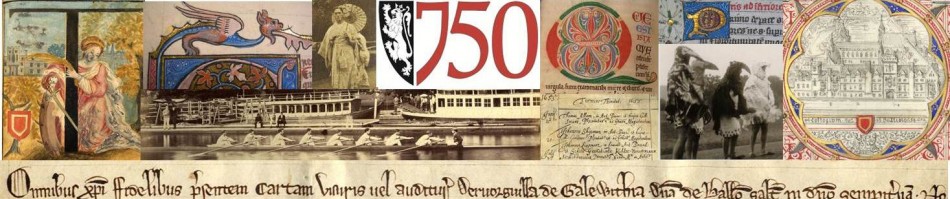

#mss2017 is open!

This year 308 people visited St Cross Church for Oxford Open Doors, 9-10 September 12-4pm both days. Here’s what they saw… and what you can see too, by making an appointment to visit between now and mid-December.

Watch this space for more public exhibition opening hours advertised later in the term, but individual and group visitors are very welcome almost any time by appointment. Visiting hours are normally Mon-Fri 10-1 and 2-5; appointments aren’t meant to be exclusive, it’s just that the exhibition and reading room are in the same space and we need to plan ahead to ensure that visitors and researchers are here at different times. Please come!

Many thanks to our Oxford Preservation Trust volunteers on both days – they staffed the front desk throughout, welcoming visitors and freeing staff to circulate and answer questions about the building, the conversion project, and the exhibition.

20+ medieval manuscripts on show, and all these people are doing the puzzle… it’s a good one, based on one of the manuscript images. Come and try it!

Start here – in fact the 1588 charter with the curtain is mounted permanently and isn’t part of the current exhibition, but it does fit nicely with its neighbour…

Case 1. College Archives D.4.1 Statutes of Dervorguilla. 1282, in Latin, on parchment. First Statutes of Balliol College, with seal of Dervorguilla de Balliol, Lady of Galloway, co-founder with her husband John de Balliol (d.1269) of the College. Shown in new mount and box, with enlarged images of both sides of Dervorguilla’s personal seal.

Case 2. College Archives Membership 1.1. First Latin Register of College Meeting Minutes 1514-1682, in Latin and English, on paper. Earliest surviving records of Balliol College’s Governing Body. Open at entries for the early 1560s, mostly concerning elections of Fellows at this stage rather than a full range of College business. Shown with images of damage and historic repairs to the last page of the volume, and illuminated medieval liturgical music manuscript reused (upside down) as binding waste.

Case 3.

L: MS 349. 15th century collection of nine texts related to the office of priesthood, in Latin, on parchment. Bequeathed to Balliol by Dr George Coningesby in 1768. Closed to show the only medieval binding in Balliol’s manuscript collection. Displayed with images of the text inside.

R: MS 350. 12th, 13th & 14th centuries, 3 medieval treatises on English law, including Herefordshire section of Domesday. Victorian vellum binding, in Latin and Anglo-Norman French, on parchment. Bequeathed to Balliol by Dr George Coningesby.

Case 4. MS 263 14th-15th century copy of texts on poetic and rhetorical composition, in Latin, on parchment. Rebound 1720s. Provenance unknown. Displayed upside down to show extensive water damage and loss to upper outer corners of the first 100 folios. Currently in unusable condition.

Case 5. MS 238E ca.1445. 5th volume of medieval encyclopedia, Fons Memorabilium Universi, compiled by Dominicus Bandini de Arecio, in Latin, on parchment. Conserved and rebound ?early 2000s. Copy commissioned and given to Balliol by William Gray, student at Balliol ca.1430 and later Bishop of Ely (d.1478).

Case 6. MS 148 2nd half 13th century. ‘Bernardi opuscula’, collection of short texts by 12th century Cistercian theologian and reformer Bernard, Abbot of Clairvaux, in Latin, on parchment. Rebound 1720s. Given to Balliol by William Gray, Bishop of Ely (d. 1478).

Case 7. MS 253 13th century. ‘Logica vetus’ and other texts by Aristotle, in Latin, on parchment. Rebound 1720s. Provenance unknown; late medieval Balliol ownership inscription.

Case 8. MS 12. Ca. 1475. Josephus, Antiquitates Judaicae (History of the Jewish People), in Latin, on parchment. Printed at Lübeck by Lukas Brandis, ca. 1475. Rebound several times, conserved 2010-11. Given to Balliol by William Gray, Bishop of Ely (d. 1478). Not a manuscript! But hand finished and decorated throughout, and mistaken for a manuscript by more than one early cataloguer. It also has a shelfmark as an early printed book, Arch.C.1.6.

And now to the chancel step for a case dedicated to the special issues of using and looking after tiny books…

Case 9.

L: MS 367. 11th century Antidotarium – medical recipes and remedies, in Latin, on parchment. Victorian binding. Probably given to the College by Sir John Conroy, 1st Bt, Fellow of Balliol 1890.

R: MS 348. 13th century Vulgate Bible, in Latin, on very thin parchment. ‘Pocket Bible.’ Rebound 1720s. In Balliol by the 17th century; provenance unknown.

Case 9. cont.

L: MS 451. 1480s. Book of Hours (Use of Rome), perhaps from Ghent or Bruges, in Latin on parchment. Early 19th century binding by by C. Kalthoeber of London. Given to Balliol by the Rev. EF Synge.

R: MS 378 Undated. Prayers to the Virgin Mary, in Ethiopic (Ge’ez), on parchment. Original wooden boards without cover. From the personal library of the Rev. Benjamin Jowett, Master of Balliol 1870-1893, other provenance unknown. This is not western or (as far as we know) medieva, but it’s Balliol’s smallest manuscript codex, and a link to the non-western manuscripts in the collection, most of which are as yet much under-studied.

Case 10. MS 396 Early 14th century. Five leaves of a noted Sarum Breviary, one of the liturgical books used for the Daily Office, in Latin, on parchment. These leaves were found in and removed from the binding of an ‘old dilapidated’ College account book in 1898, by George Parker of the Bodleian Library.

And back to the nave for a case full of medieval title deeds…

Case 11. College Archives E.1. 1320s-1350s. Title deeds relating to property and an advowson at Long Benton (Much/Mickle Benton) near Newcastle, given to Balliol College by Sir Philip Somerville in 1340, in Latin, on parchment, with seals.

Case 12. MS 116, later 13th century. Commentary by Eustratius, an early 12th century bishop of Niceaea, on Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, in Latin, on parchment. Rebound 1720s. At Balliol by the late 14th century; provenance unknown.

Case 13. MS 277, late 13th century. Aristotle’s Metaphysics, and Meteorology, trans. Moerbeke, and Ethics, trans. Grosseteste, in Latin, on parchment. Rebound 1720s. May have been at Balliol in the 14th century, alienated and returned in the 15th; given by Mr Robert Rok (Rook).

Case 14. MS 384 15th century. English Book of Hours according to the Use of Sarum, in Latin, on parchment. 18th century binding. At Balliol since the 18th century; provenance unknown.

Case 15. MS 210 1st half 13th century. Several texts by C12-13 University theologians, in Latin, on parchment. Rebound 1720s. Given to the College by Roger Whelpdale, sometime Fellow of Balliol and Bishop of Carlisle in 1419-20 (d. 1423).

Case 16. MS 173A 12th and 13th century. Two collections of short texts bound together, on medieval music theory, in Latin, on parchment. Rebound 1720s. Given to Balliol by William Gray, Bishop of Ely (d. 1478).

Case 17. College Archives B.22.1, the oldest document in Balliol College’s archives, is an undated charter of ca. 1200, recording a grant of the Church of St. Lawrence-Jewry, London, with rents etc., from Robert, Abbot of St. Sauve, Montreuil, to John de St. Lawrence, with others.

Case 18. MS 354 Early 16th century. Commonplace book of London grocer Richard Hill, in English, Latin and French, on paper. Medieval song or carol texts, literary extracts, poems, religious and spiritual texts, notes on farming and trade, recipes, proverbs, etc. Original limp parchment cover. Provenance unknown.

Case 19. MS 240 12th and 14th centuries. Miscellany of religious texts, in Latin, on parchment. Conserved and rebound by Andrew Honey, 1990s. From the priory of Monks Kirby (Warwickshire). Given to the College by Richard Bole, Archdeacon of Ely (d.1477).

In addition to a wealth of original manuscripts exhibited, there are also several forms of supplementary material – here, a display on loan from OCC with more details about their work for the colleges’ collections – and Balliol items used for three of the four illustrations: B.22.1 above, MS 12 above, and Robert Browning’s DCL gown (awarded 1882). On the right visitors can touch and feel samples of just a few of the materials they use for repairs, e.g. papers and tissue, fabric and thread, parchment and leather.

At levels both lower and higher than the exhibition cases are more images from Balliol’s manuscript, for sheer enjoyment. Above, a much enlarged opening of MS 451, the 15th century Book of Hours; below, two miniatures from MS 383, a much-studied high-status 15th century copy of Ovid’s Heroides ina French verse translation.

The corridors around the sides of the church not only provide access to wall memorials and stained glass but also offer an unusual insight – windows into the climate-controlled repositories where the archives, manuscripts, and early printed books are stored.

With several hundred visitors in a few hours, there is always a queue for the loo during Open Doors – but even here one can enjoy more details of illuminated initials from Balliol manuscripts.

Some of the more than 300 Open Doors 2017 visitors enjoying the building, the manuscripts and a challenging custom jigsaw, based on an image from one of the manuscripts on display.

manuscripts boxing

The benefits of last year’s condition survey of manuscript books continue apace: during last year’s manuscripts condition survey, we listed 155 manuscripts either unboxed or inadequately boxed. Boxing is a quick and effective – and relatively inexpensive, depending on the type of box – way to protect all kinds of archival material from light, dust and handling damage, as well as providing a certain amount of buffering from the environment.

First batch of 25 to be measured – these manuscripts are in good condition and require only light cleaning. Once they are boxed they will not need further conservation attention for a good long time, we hope. This will mean we can cross two dozen off our list of 155 quickly. The next tranches of mss will be measured in batches as well, in order according to how much repair they need, starting with those needing least binding repair, and avoiding those needing major text block repairs until the end. This isn’t just about getting through the list quickly: any change to the binding – and even some major interventions to the text block – may alter the outer shape of the book and therefore the box. Those will need treatment before they can be accurately measured for a box. Some may need a folder or wrapper in the interim.

The first lot of custom-made boxes has arrived from the Bodleian’s boxing and packaging department:

a surprisingly small package…

contains a certain number of boxes…

which are bigger on the inside than the outside! clever packing 🙂

one type of box – drop-spine, mostly used for larger, thicker or hardback volumes; several have string-and-washer closures on the fore edge for extra security and a little pressure to help keep the boards in shape

the other type, a robust four-flap folder, for thinner, smaller and soft-back volumes

all done – another two dozen manuscripts safer on the shelf and during production!

conservation – manuscripts survey summary

Balliol College Archives & Manuscripts and the Oxford Conservation Consortium recently completed a condition survey of all of Balliol’s medieval and early modern manuscript books, as well as a number of later items catalogued in the same series. (See RAB Mynors, Catalogue of the Manuscripts of Balliol College Oxford, OUP 1963.)

The survey of 497 items, ranging from single sheets and home made booklets of a few bifolia to palm leaves strung between wooden boards and huge bound volumes on parchment, took 39 sessions averaging 3 hours each (ca 120 hours total, more than 4 items per hour) over 29 weeks, from mid-January to the end of July 2014. The staff hours required were twice that, as each session required two people: a conservator handling the manuscripts and a Balliol staff member entering data into an Access database on the OCC laptop. This was a much more efficient use of the college’s OCC subscription time than having the conservator enter the data as well as assess the manuscripts. It also provided a once-in-a-career opportunity for Balliol Library staff, particularly the Archivist, who is responsible for the manuscripts, to become familiar with every manuscript in the collection, in some detail. Most of the data was entered by the Archivist, but all members of Library staff participated during the course of the survey, as did five members of OCC staff. The process was speeded up considerably by having the 10-15 items scheduled for each day’s session ready in advance and waiting on a trolley in the reading room when the conservator arrived.

The survey

Each item received an average of 15 minutes of assessment, but in practice it varied from 10-25 mins depending on the complexity and condition of the item. The survey template included sections for descriptions of each item and assessment of its current physical condition as well as recommended repair/conservation treatment: survey information (date seen and name of assessing conservator); physical dimensions; current boxing or other container; text block materials, binding type, cover and board materials; attachments and supports, sewing, endbands, fastenings, text block edges, binding decoration, labels or titles; condition of text block and its media; condition of binding (cover, boards, joints, sewing, endbands, labels); whether the volume had been rebound or rebacked; its overall condition or usability; any treatment required or recommended, including new or replacement preservation boxing/packaging; and any other notes.

Equipment required

- good lighting and seating, a large stable table

- large document trolley

- measuring tape

- conservator’s tools e.g. large tweezers, selection of dentistry tools!

- magnifying glass

- cold (LED) desk lamp

- foam wedge book supports of various sizes

- bone folders

- lead weight/snakes

- laptop for entering data

The database

The template for the survey database was adapted for the Balliol survey into Access format from OCC’s existing Word document, which had been used for several previous similar surveys at other colleges. We also kept a paper copy of the form handy during survey sessions for easy reference to descriptors. It was pre-loaded with all the MSS numbers, short titles for identification and centuries of production. At the end of each session the updated database was copied to a memory stick and to the archivist’s networked drive.

Having the survey information in a database format, not only electronically searchable but also sortable, makes possible many of the future uses of the data listed below.

Database suggestions

We found that while the template provided an excellent structure for focused investigations and vocabulary for nearly everything we needed to describe, it would have been useful to have a notes field as well as tick-boxes for description of the writing materials. Most texts fell into the usual categories of iron-gall ink, black-brown ink, pigments etc, but we also found various types of ‘pencil’ in some of the medieval books, and modern inks, pencil and typescript in some of the modern mss. In some cases we noted these in the Notes field at the end, but more information would have been captured with another field in the writing materials section. The same applied to the Bindings description section, especially for some of the unusual amateur bindings and coverings. We began noting the number of binding supports partway through and found it a useful addition.

Data entry was done directly into the Table view of the Access database; this helped to keep investigations very focussed, as the Table view layout made it difficult for the data enterer to skip around between sections, but an Access user interface would give access to more fields at once and should be considered for future use. Some users might prefer to convert the database to Excel, and we have found it useful to extract and convert parts of it to Word for reports and printing.

Aside from the professional and custodial benefits to staff and the college, we all enjoyed this survey immensely! It was an exciting time of (re)discoveries in the collection and much learning for all involved.

Benefits and uses

1) The most obvious function of the survey is to inform conservation treatment priorities for the future, but it is far from the only one. For each manuscript, its current condition and recommended treatment will be balanced with its contents/research interest and likelihood of exhibition or teaching use. We have good data going back more than 10 years on the ‘research popularity’ of the manuscripts.

2) In addition to conservation treatments needed, the survey has identified basic important preservation improvements e.g. numerous mss are not yet boxed, or need wrappers inside their otherwise good acid-free envelopes

3) The survey acts as a shelf check of the manuscripts.

4) Although the manuscripts were catalogued by Mynors, some of the descriptions date from as early as the 1930s and many reflect Mynors’ own research interests, heavily biased toward the texts of western medieval books. The survey has helped to identify underdescribed manuscripts needing improved catalogue entries to serve the wider interests of students of codicology and the history of the book. Areas particularly needing improvement are descriptions of historic bindings, details of illumination and book decoration, early modern manuscripts and non-western manuscripts.

5) Electronic records make it easy to flag the manuscripts’ physical condition to potential users on our website, so it is clear in advance which need (extra) special care in handling and which (few) will not be produced to researchers in their present condition. This will inform staff handling and manuscript-specific instructions on handling to readers. Better handling will improve long term preservation by decreasing the likelihood of further damage.

6) Similarly, exhibition/loan requests can receive quick and detailed responses about the suitability of specific mss for display and particular considerations needed. Where necessary, treatments can be prioritised or alternative candidates found. Staff will be able to balance the physical exposure of manuscripts across the collection rather than repeatedly displaying the same few well-known and regularly requested ‘treasures’. Increasing the breadth of manuscripts displayed will lead to institutional appreciation of the collection as a whole rather than a set of highlights with an anonymous hinterland of unknown quality.

7) Staff can easily find FAQ statistics e.g. largest, smallest, oldest, unusual characteristics, shared features, authors, texts, dates; these will be useful for reports, teaching, outreach, displays and online features.

8) Improved staff/institutional knowledge of the whole collection has already led to use of some of the less-frequently consulted (and formerly less valued) manuscripts for teaching and school outreach purposes.

More benefits and further uses of the survey are still emerging:

- Conservators are adapting database template for use in similar surveys with other colleges.

- a research-experienced volunteer is gaining curatorial experience and starting improvements to descriptions of codicological and decorative features to support teaching, research and exhibition requirements (see (4) above).

- an academic researcher has been provided with the most complete list available to date of all Balliol manuscripts within a date range containing illumination (in this case, decoration using pigments and metal e.g. gold leaf). The list derived for these criteria from the survey database is considerably longer than any comparable list yet in print.

A few survey numbers

- MSS surveyed: 497

- people involved: 9

- staff hours: ca. 240 (ca. 120 each Balliol and OCC)

- no. & % of mss in good condition: 211

- no. & % of mss in fair condition: 196 + 22 in ‘fair-to-good’ condition, indicating that some minor repairs would make the manuscript significantly safer to produce.

- no. & % of mss in poor condition: 38 + 24 in ‘fair-to-poor’ condition, usually meaning that one of the boards is detached but the MS is in otherwise fair condition

- no. & % of mss in unusable condition: 6

- largest MS: two answers: largest volume MS 228, dimensions 480x350x125 mm, vol 0.021 m3; and largest boards MS 174, dimensions 480x370x090 mm, vol 0.0159 m3 .

- smallest MS: MS 378, a book of prayers in Ethiopic, written on parchment with wooden boards and a nice example of Coptic binding. It measures 081x062x035 mm.

- oldest MS: MS 306, part of which is a 10th century copy of a text by Boethius

Have a look at our conservation survey series of posts for more details of our discoveries! Still more to come…

conservation survey notes 13

Balliol MS 385 is written in Pali on lacquered and gilt palm leaves enclosed and strung between painted wooden boards.

Detail of one of the boards

The inner side of one board and the outside leaf

Detail of an outer leaf

leaves from the middle of the manuscript, with text and decoration

detail of decorated leaf

Balliol has few Oriental manuscripts – the term under which all the non-western mss in languages and scripts from Pali to Persian, Hebrew to Hindi, have been lumped together. Most of them were given individually to the College as antiquarian curiosities, and they have not, on the whole, been evaluated, described or studied much at all in comparison with the collection of western manuscripts. But there are discoveries still to be made!

A description of MSS 385 and 386 by Prof FW Thomas, cited by Mynors as ‘kept with the MSS’, is lost, so as far as we know Balliol does not have information about the date or origins of this MS. There is no obvious documentation of how it came to Balliol, but there is a lot of acquisition information, at least for the 20th century, in the Annual Record, so we will at least survey that to see what we can discover.

In the meantime, our descriptions remain inadequate, but thanks to the efforts of archives, libraries and museums to put images from their own collections online, it is possible to put these ‘Balliol orphans’ in some kind of context with other manuscripts of their kind(s). I have found some (to the untrained eye at least) similar manuscripts – and therefore several useful descriptors and explanations of particular features – at:

- Trinity College Dublin Digital Collections (Dublin, Ireland) – try searching for ‘manuscript’ and then add Hebrew, Arabic, etc. This post from M&ArL@TCD’s blog about a Pali MS from Burma has images of something similar to Balliol 385.

- Walters Art Museum Illuminated Manuscripts (Baltimore, MD, USA) image collections on Flickr – includes a large collection of Islamic manuscripts

- The Wellcome Library (London, UK) image collection – search for e.g. ‘Pali’

- Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, NY, USA) – a small online exhibition on ‘Early Buddhist Manuscript Painting: The Palm-Leaf Tradition’

- Northern Illinois University (DeKalb, IL, USA) – manuscript collections in their Southeast Asia Digital Library

Very little of the British Library’s large Southeast Asia collections is online, either images or descriptions, but you can find some images here: http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Default.aspx

For background knowledge rather than images:

- The Fragile Palm Leaves Foundation

- The Pali Text Society

- The Wellcome Library’s Catalogue of the Burmese-Pali and Burmese Manuscripts

conservation survey notes 12

Balliol MS 452 is a copy of the Koran, given to the College in 1983. The donor did not have information about its date or provenance. We will be asking experts in the field(s) to examine Balliol’s small collection of Oriental manuscripts and describe them in detail, most for the first time. Watch this space!

Physically, the book is currently in unusable condition. The spine and one cover are detached, and the unsupported sewing is weak with some breaks, making the textblock unstable. Any use in this state causes damage – we disturbed it as little and as briefly as possible for this examination, while documenting as much as we safely could.

The first folio features areas of illumination using gold and pigments above and below the text and on two, perhaps formerly three, sides of the border. This page shows some old repairs, of which there are many throughout the volume.

above, showing f1 with the blue linen spine lining exposed

The two sections of the fore edge flap have become detached, and the hinges between the three parts of the cover are mostly lost.

The red leather cover, now darkened, was painted with silver and gold or pigments resembling metals. The various layers, which would not have been visible when the book was new, are now showing more clearly as the materials age and wear.

The small square gold-coloured areas are made separately and stuck on – some are beginning to lift as the adhesives lose their strength.

A view of one of the endbands, showing the typical zigzag pattern, now broken about halfway.

This volume was housed until recently inside what was once a beautiful dark green silk velvet bag, evidently specially made for it. A stub remains from the bag’s lost tie, in a rather natty check or plaid. The textile itself needs conservation, and removing the book from the enclosure or replacing it is only causing further damage to both items, so they will be kept separately – but still together. Ideally, one both items have been treated they could be housed in separate areas of the same box.

Thanks to the survey, we hope that both the history and the future of this book will soon become clearer!

conservation survey notes 4

Today we have naming of parts – binding parts.

Balliol MS 248C – the front board is detached, held on only by the cloth lining the inner joint.

And here’s why – although the double alum tawed supports are clearly present in the spine…

… when the manuscript was rebound, the supports were cut, and not attached to the upper board at all. The leather covering the outer joint, which was doing a lot of the work of holding the board in place, has, unsurprisingly, split under the strain.

Close up showing the stumps of the supports on the spine side (lower part of photo) and the channels cut into the board for the supports to continue into – but the channels are empty! The linen inner joint, now damaged itself, is the only attachment between spine and board.

what’s all this then?

St Cross does not look quite its usual serene self at the moment; the aforementioned kitchen refit on the Broad Street site has precipitated a move of several hundred boxes of modern personal papers from the recently-encroached-upon Music Room to St Cross. Above, the first tranche of Broad Street arrivals, plus 250 brand new archive boxes.

Several collections housed in the non-archival standard cardboard boxes shown here were moved out of the vestry repository to make way for the Broad St influx, and are being transferred to archival boxes before moving back into another repository. This is because the old boxes are 1) nowhere near acceptable quality for permanent storage of archival collections, 2) large and therefore too heavy to move safely when full, particularly if stored at floor level or at any height requiring a step or ladder and 3) prone to handles falling off and/or bottoms falling out, a major preservation and handling hazard!

The orderliness is deceptive – that’s about 70 big boxes tidily stacked in the chancel, the contents of which will occupy at least 200 green boxes.

Happily this time, this photo is also spatially deceptive – this little repository unit, which has just been emptied of what’s now waiting in the chancel, will hold nearly 800 green boxes. By next week it will be full again.

I have had invaluable help with all this adjusting shelving, reboxing and putting away for a few days in the last couple of weeks from Will Beharrell, formerly a successor of Fiona’s as graduate trainee in the Codrington Library at All Souls’ and now a librarianship student at UCL, whom I thank very much for this work and his excellent start on a list of Richard Hare’s correspondence. However, there is a lot more to come, and until it’s all squared away I won’t be getting much else done, because the boxes need to be shelved in the repository so they are secure and easy to produce, and they cannot just sit around occupying the nave and chancel when readers and other visitors need the space and a good atmosphere to work in.

The Unlocking Archives series of talks on interesting discoveries in Balliol’s special collections will run again this year, starting next month!

Q&A: digitisation

Q: Responding to a good query from @ojleaf for the #AskACurator conversation on Twitter: If you are digitising precious documents, does it frustrate you if people still want to handle the original?

A: No.

See previous post about the constant balance between preservation and access.

First, for ‘precious’ read ‘OLD.’ It’s hard to remember that a medieval manuscript in good condition, with its illustrations still bright and its parchment still smooth, is at least FIVE HUNDRED years old and may be much older. Parchment is very tough stuff, and ancient books can be enormous and very heavy. It is hard to remember that such physically formidable objects really are fragile. That doesn’t necessarily mean that pages will tear easily, or even that the books will break into bits if you drop them. They are physically vulnerable, especially the ink/paint and bindings, but less obviously, they are also chemically vulnerable – to our warm breath, to the oils on our hands, to the light we read by.

‘Because I want to feel closer to the past’ is a completely understandable reason for someone to request direct access to, say, a medieval manuscript book, but not a valid one on its own. I sympathise (all very well for me, I have direct contact with these things every day – at least in theory) but in principle, what seems more important to me (and there is always a balance to be struck between the two) is access to information rather than access to objects. HOWEVER! if a researcher is able to demonstrate that he or she needs information from the original document that is not obtainable from a facsimile, then of course I’ll produce the original. This happens quite often. Using facsimiles, especially good quality digital images, is a great way for most researchers to get most of the information they need without having to expose the original to the wear ( = damage) of repeated handling and changes in light, temperature and humidity.

Eventually a researcher may well have to come and check the original manuscript in person, but advance preparation and familiarity with the contents, layout and visual characteristics of the manuscripts – and potential problems – will make the time spent with the originals that much more productive. Thanks to digital images, that time may be reduced from days or weeks to a matter of hours. In practical terms, having access to decent digital images, preferably in advance of a visit to see the original (but better afterwards than never) will usually mean:

- ability to

- view images at much-magnified resolution, i.e. larger than the original

- manipulate images to improve colour, contrast etc – so many manuscripts are written in brown on brown

- view pages in any order, any number of times

- reconstitute original order in cases of misbinding

- juxtapose images of pages which are not physically facing each other

- view more than one opening at a time

- use images in illustrations for discussion, publications presentation, teaching etc

- sit in comfort at home, at own computer, in own chair, with own mug

- reduction of

- number of research trips

- travel time

- travel and accommodation costs

- time spent in archives, where (with the best will in the world) light may be low, temperatures unpleasant, access awkward, chairs uncomfortable, and pens, water, cough sweets and tea not allowed!

We hope that’s an improvement for everyone. And we do have exhibitions of all sorts of items from the special collections – even if visitors are not able to leaf through a 400-year-old Aldine imprint, they can get pretty close to a good number of Exciting Old Things and hopefully find some interesting information about them in the captions or catalogue. Maybe some will be inspired to start their own research projects…

Q&A: digitisation

I was recently asked: ‘I noticed that quite a bit of material from your archives has been digitized, and that you have put it to fine use by widening access to the collection on the website and through online exhibitions. I wondered how you are going about digitizing the items – are you working in-house, or are you using an external organization to do it, or a mixture of both? Please could you tell me how this is being financed, and if you are aiming to digitize the whole archive or just a part?’ This isn’t the first time I’ve been asked about my digitization programme at Balliol, and it prompted a bit of an essay on how I do things now and how that has changed since I began in October 2010. So here’s is an update to what I was thinking then.

I do the digitising myself – I have an excellent A3 scanner and a serviceable but outdated camera which I’m about to replace. I allocate a few hours a week to scanning & photography so that it progresses regularly, if not quickly, but I am posting about 2000 images a month these days.

The occasional exception is when someone wants to photograph an entire manuscript or series for their own research; in such cases I ask for copies of the images and permission to publish them online and make them freely available to other researchers, with credit to the photographer of course. So far the few people I’ve asked have been very happy to do this, since they have had free access and permission to photograph. (Sometimes their images are not as good as mine, so then I don’t bother!)

There are also numerous documents in the collections that are just too big for me to photograph – eventually, if and when they are asked for, we will have to think about having someone in to photograph them systematically. So far the multiple photos of each that I or the researcher have been able to do has sufficed.

For now at least, I have decided against a systematic digitisation of our microfilms of the medieval manuscripts. This would involve a lot of time and effort to fund and arrange, the images would all be black and white, and of variable quality, and there are knotty questions of copyright as well. Some of the MSS were only partly microfilmed, and none has more than a single full-page perpendicular view for each page – no closeups or angles to get closer to initials, erasures, annotations, marginalia or tight gutters, so there would still be considerable photography to do anyway. Also, see below.

Why don’t you apply for a grant and have a professional photographer do more than you can do yourself?

So far, I’m able to fulfil reprographics orders in a pretty timely manner and to a standard that satisfies enquirers. Aside from cost and time management for individual orders, because I can respond individually and fit them in around my other tasks, the great advantage of doing the digitisation myself is that I am getting to know the collections extremely well. If we had an outside photographer do it, all that direct encounter with each page would go to someone with no real interest in the collections, what a waste. This way, I’m checking in a lot of detail for physical condition, learning to recognise individuals’ handwriting, discovering/replacing missing or misplaced items, prioritising items that need conservation or repackaging, noticing particularly visually attractive bits for later use in exhibitions and so on, and not least ensuring that items are properly numbered – which many are not!

What is the cost?

Because I work reprographics orders into my regular work schedule, there is no extra cost, except the £50 or so fee every 2 years for our unlimited Flickr account.

Because I work reprographics orders into my regular work schedule, there is no extra cost, except the £50 or so fee every 2 years for our unlimited Flickr account.

Do you charge for access?

I always mention that donations are welcome, but in general I do not charge for reprographics. Most of the requests are from within academia, and I think HE institutions have a responsibility to be helpful and cooperative with each other and with the public, particularly when it comes to access to unique items. On the one hand, I know that special collections are extremely expensive to maintain, and often have to sing for their supper, but on the other I know how frustrating it is to be denied the chance to take one’s own photographs and then to be charged the earth for a few images. Institutions like ours, whose own members may need such cooperation from other collections and their curators, should probably err on the side of the angels er scholars! Most of the other requests for images are for private individuals’ family history research purposes, and since many of those enquirers would otherwise have no contact with Balliol or Oxford, I think it’s good for the relationship between college, university and the wider public to be helpful in this way. Family history is usually very meaningful to researchers, and they remember and appreciate prompt and helpful assistance.

Balliol College reserves the right to charge for permission to publish its images, but may waive this for academic publications.

Are you planning to digitise all the collections or just parts? What are your priorities and how do you determine the order of things to be done next?

Most of the series I’ve put online don’t start with no.1. All the reprographics I do now are in response to specific requests from enquirers, and I don’t seriously intend, or at least expect, to digitize All The Things. Although 40,000 images sounds like a lot, and there’s loads to browse online, I’ve barely begun to scratch the surface; most collections aren’t even represented online – yet… This way, everything I post online I know is of immediate interest to at least one real person – if we did everything starting from A.1, probably most of it would sit there untouched. For the efficiency of my work and for preservation of the originals, digital photography is marvellous, enabling me to make every photo count more than once rather than having to photocopy things repeatedly over the years.

On the other hand, if someone asks for images of one text occupying only part of a medieval book, I will normally photograph the whole thing; or if the request is for a few letters from a file, I will scan the whole file. It’s more efficient in the long run, as a whole is more likely to be relevant to other future searchers than a small part.

What about copyright?

I probably should mark my own photos of the gardens, but I don’t think anybody will be nicking them for a book and making millions with it. As for the images of archives and manuscripts, of course I am careful to avoid publishing anything whose copyright I know to be owned by another individual or institution, but for older material that belongs to Balliol, I’m with the British Library on this one. I think as much as possible should be as available online as possible, for reasons of both access and preservation.

I probably should mark my own photos of the gardens, but I don’t think anybody will be nicking them for a book and making millions with it. As for the images of archives and manuscripts, of course I am careful to avoid publishing anything whose copyright I know to be owned by another individual or institution, but for older material that belongs to Balliol, I’m with the British Library on this one. I think as much as possible should be as available online as possible, for reasons of both access and preservation.

We do have some collections whose copyright is held by an external person or body, and in some of those cases I am permitted to provide a few images (not whole works) for researchers’ private use, but cannot put images online or permit researchers to take their own photos.

How do you make images available?

Now that other online media are available, I am reducing image use on the archives website, to use it as a base for highly structured, mostly text-based pages such as collection catalogues, how-tos, research guides etc, as this information needs to be well organised and logically navigable. These days I am using this blog for mini-exhibitions discussing single themes and one image, or a few at a time.

Flickr is a good image repository for reference, not so much for exhibitions – I’ve written about that at https://balliolarchivist.wordpress.com/2013/05/01/thing-17/

I expect I will have rethought the digitisation process again in a couple of years’ time!

archive move essentials

Here’s my list of the absolute essential preparations by the archivist preparing to move the collections into a new repository – or indeed into storage and back to the old one!

- Condition survey of the things to be moved, and priority conservation for anything likely to be damaged in the move (now that really is an ideal…)

- Item-by-item check of every single thing against whatever catalogues there are – combined with improving the lists where possible. It’s essential to know what’s where, what’s been misplaced and what’s really missing *before* the move!

- Proper numbering and labelling of anything that isn’t so labelled, ideally at item level of course.

- Plan EXACTLY where each section and each box is going to go in the new repository and have a code to mark the boxes with their new bay/shelf numbers. Label the new repository clearly before the move starts. Be sure to include provision for any outsize, awkward, delicate or otherwise complicated items!

- If you are having anyone else do the move, make sure they are using crates or whatever that will hold your standard size boxes securely, and that they won’t stack more than e.g. 3 boxes high in a crate. Identify any non-standard size items in advance and decide how to pack those for the move, individually if need be. We used 2 large sizes of ‘Really Useful Boxes’ and they were brillliant. Also sturdy.

- When the move starts, make sure you have sealed the boxes and know exactly what’s in them, and have a checklist of what boxes go in which crate. Check in and out at either end.

In short, make a lot of lists and check them twice.

Of course, environmental monitoring should begin asap in the new building, and the move should not start until conditions are really stable and where you want them.

The move must be gradual enough that environmental conditions are not thrown out of whack, and so that you have enough time to sort boxes straight into their new place – shifting things around later is a waste of time, money and effort. Ideally, you should need to move each box only once.

These are basic essentials, not frills. The needs of historic documents are different from those of ordinary office paper. I hope your organisation will be enlightened enough to give you help, support and above all enough time to plan and carry out the move properly. Good luck!

Handling archives and manuscripts

So far 2012 has been a busy one with many researchers visiting the Historic Collections Centre. I’ve observed varied technique – or lack thereof – for handling and supporting manuscript books, rare volumes and archives of various formats, and thought I would round up some of the most useful handling guidelines I could find. I’ll be adding them to the website as preparatory reading for all researchers. This will save me barking a lot of ‘Don’t!’s at visitors… Of course I suggest politely really, but the effect is often the same however considerately you break an hour’s silent concentration!

One thing I’ve observed is that researchers often rush when handling manuscripts. This is because they are in a hurry, and because they are excited about their investigations. It can be very damaging to the manuscripts. There are several things researchers should keep in mind:

- This book is [x] centuries old. We want it to last [x] more centuries.

- Damage is cumulative, so we need to minimise it during our brief curation or use of this manuscript.

- Turn pages s*l*o*w*l*y and gently, from the middle of the edge as long as the text doesn’t go right to the edge

- Avoid touching text, not only with your fingers but with lead weights or papers

- Don’t lean on the book or push down on pages to make them open more. Think of what is happening to the binding.

- It is not (usually) the parchment itself that is particularly fragile. It’s the inks and especially the binding.

- Careful handling is free. Conservation repair work is extremely expensive.

It’s important to take the time to consider each item’s structure and individual needs for correct support – and not only when it first arrives at the desk. The shape of a book and the stresses within its structure change a great deal as the pages are turned, and supports may need to be moved several times during consultation.

The guidelines below concentrate on manuscript volumes, but include and often apply to other formats as well. None of them is complete (in my opinion) so it is important to look at several – or preferably all of them, they’re only short – to get the whole picture.

CAUTION if you’re using these in a library or other quiet area – some of the videos are silent (thanks, BL!) but others are not.

- British Library

- Bodleian Library – link defunct and guidance not replaced, pages archived here

- National Park Service Conserve-o-Gram

- Harry Ransom Centre, University of Texas at Austin

- Auckland Libraries

- Specifically about correct use of foam book supports

- Folger Shakespeare Library – very good EXCEPT the use of the lead weight snake on the front cover of the small book!

- Practical videos about handling many different formats of books and archival material from the British Library

- Glasgow University Library and several of their other videos on handling different formats

- Harvard Special Collections

horns of the dilemma

Access and preservation – pillars of the profession, or, the archivist’s Scilla and Charybdis

I detest being pushed into the role of curmudgeonly dragon, so I wish people would not request to ‘glance through’ (e.g.) 19th century literary papers because they like the subject’s poetry. This is just not a good enough reason to ask to handle fragile, light-sensitive documents that are 150 years old. Use of archives is normally the final step of primary research on a particular thesis (research question), after thorough investigation of secondary and published sources. And I will say so, because my first duty is to the college and the preservation of its collections – otherwise there will soon be nothing left! But thank goodness for digitisation and the huge increase in access it makes possible. I am as committed to increasing access to the information within the collections as I am to physical preservation of the originals.

While the corollary of increased access via digitisation is increased preservation of the original, its flip side is decreased access to the original. I do not produce manuscripts that have been digitised except for codicological queries that truly cannot be answered by consulting the facsimile. There is something special about direct contact with an ancient codex, but the fact is that every exposure to light, fluctuations in temperature and humidity and handling, however careful, inevitably causes cumulative and (at least in the case of light) irreversible damage to paper and parchment.

Access and preservation often pull in opposite directions, and the needs of the reader and those of the archives can appear to be in conflict. But archivists have to hold these two poles in some kind of balance, because without preservation there will soon be no access, and without access – and I emphasise that in most cases the important thing is access not necessarily to the physical objects but to the information they contain – preservation would be pointless.

Q & A – digitisation

Q: The manuscript scans on flickr are very exciting! Are there plans for a full systematic digitization? And do you take requests?

A: Thank you! Most of the medieval manuscript books have been microfilmed over the years and I’m looking into digitisation of the microfilms in the first instance, as less invasive for the MSS. Whether we go ahead with that depends on cost and quality of the end product – I’m not convinced scratchy b/w films are worth it, but on the other hand most of our MSS are unornamented, so little information is lost in black and white.

Obviously digital images would be better (colour for one thing) and images like those on Early Images at Oxford for all the MSS would be the ideal, but there isn’t budget or time for that, so the digitisation I do so far is in reaction to specific scholarly requests (hence often partial) rather than systematic. It also depends on the physical state of the manuscript – we’re part of the Colleges Conservation Consortium but of course it’s a long process.

As far as digitising the archives is concerned, again it’s reactive rather than systematic and is subject to preservation considerations. After about 1550 many of the documents are bigger than A3, sometimes A2 or even bigger; they’ve always been stored folded down to A4 or smaller, and there’s just no way I can scan those. But the little medieval deeds, though several hundred years older, are generally easily scannable. It’s a question of time and priorities – eventually they would make an excellent basis for an online palaeography learning resource, as well as for the information they contain.

paper clips

Lately there has been a long thread on the Archives-NRA discussion list on the best kinds of paperclips to use on archive collections, and although I sympathise with the undoubted incredulity of the rest of the world that anyone could care two pins (or brass clips) about this kind of thing, I remembered that I wrote this in my first year of work as a qualified archivist, at Glasgow University Archives.

Brass, stainless steel or plastic paper clips?

A survey of advice on fasteners for paper collections

A survey of advice from a variety of sources including Conservation Online, including their discussion list for conservation professionals and recommended external links, the National Preservation Office and the National Archives revealed the following:

Paper clips

The National Preservation Office says in its Basic Handling Practice leaflet that ‘Pressure tapes, metal or plastic fasteners such as paper clips and pins should never be used, and must be removed by trained staff.’ The use of any paper clips at all is a compromise; the best way of keeping a small set of papers together is to put them in an acid-free paper folder or enclosure, but if there are many of these sets, the extra paper takes up a lot more space. Another point against using fasteners of any kind is the difficulty of getting readers to use them properly: systematically removing them one by one to examine individual papers (rather than folding them back on each other, bending and folding papers and risking tears and further damage) and similarly putting them back!

Several sources recommend as a safer alternative, although not ideal, stainless steel paper clips with a slip of acid-free paper between the clip and the documents. This prevents direct damage e.g. rust from the metal clip but would be fiddly to implement and difficult to enforce with users. The increased use of acid-free paper would partially offset the overall lower cost of stainless steel paper clips. This option tends to be recommended by sources in the U.S.A., who seem to use mostly stainless steel or aluminium paper clips rather than either plastic or brass.

Other fasteners

Archival fabric tape is also an unacceptable way of keeping bundles of papers together as it causes immediate stress and tearing on the outer edges of the documents, the tape tends to be used to remove bundles from the box, users are often not careful enough about how they undo it, and further damage may be caused by retying the tape too tightly. Papers in a bundle are often not exactly the same size, which exacerbates the problem. Bundles of papers, leaflets etc. too big for a paper clip should be kept together by a paper or card folder or enclosure, as should any particularly fragile papers. The folder can then be secured with fabric tape if necessary. I should perhaps mention that all the sources I consulted were unanimous and emphatic in stating that the use of any pressure-sensitive tape, including ‘archival’ or ‘conservation’ repair tape, for mending tears in paper, is not advisable.

Metal pins rust, make holes in paper, cause wrinkles and are a safety hazard. They must be removed – this is often difficult in cases where rust is holding a number of sheets together. Treasury tags, often used to hold larger numbers of papers together in one corner, are also unacceptable – they require making a hole in each sheet and do not hold the sheets in a stack, so that it is easy for them to fall and tear during handling.

Plastic clips

Plastic clips, and Plastiklips are mentioned specifically, are cited by Conservation Online discussions as causing more bending and crimping of paper than metal paper clips. These indentations will eventually lead to tears. They may also offgas in the event of a fire; a more ordinary risk is that they will break, either actually tearing the paper or allowing it to slosh about in the box or fall on the floor when accessed. Plastic tends to degrade over time and will become brittle. Also, plastic clips cannot be bent to adjust to slightly thicker groups of papers and will simply exert more pressure, increasing both damage to the papers and the likelihood of the clips breaking. Plastiklips expand a bit but this expansion exposes the papers to another set of edges, causing more crimping. They are no less likely to cause tearing when attached or removed than properly made metal clips. Plastiklips are significantly thicker than most metal paper clips and even when the placement of clips along the top edge (the safest place as it will be noticed immediately) is staggered, cause uneven stacking of papers in boxes or folders, leading to possible damage and wasted space.

Brass paper clips

The HMC’s Standing Conference on Archives and Museums specifically recommends the use of brass paperclips, and the Conservation Online discussion group cites their use as standard European practice. They are inert and will not rust, break or become brittle. Use of any paper clip is a compromise, but where it is necessary or practically expedient solid brass paper clips are the best option.

-Anna Sander, 15 April 2004

======

2013 update: another article on choosing the right archival fasteners! by Beth Doyle, a conservator at Duke University Libraries.

======

Selected sources

Conservation On-line Discussion List

http://palimpsest.stanford.edu/byform/mailing-lists/cdl/

HMC SCAM

http://www.hmc.gov.uk/scam/Infosheet3.htm

Museum Management Program (U.S.A.) Conserve-o-grams

19.5 Removing original fasteners from archival documents

http://www.cr.nps.gov/museum/publications/conserveogram/19-05.pdf

19.6 Attachments for multi-page historic documents

http://www.cr.nps.gov/museum/publications/conserveogram/19-06.pdf

Northeast Document Conservation Center. ‘Preservation 101: an online course.’

http://www.nedcc.org/p101cs/p101wel.htm

NPO. ‘Good handling principles and practice for library and archive materials.’

http://www.bl.uk/services/npo/practice.pdf

Oxford University Library Preservation Services

http://www.bodley.ox.ac.uk/dept/preservation/information/traditional/traditional.pdf

Smithsonian Centre for Materials Research and Education. RELACT: ‘Basic handling guidelines for paper artefacts.’

http://www.si.edu/scmre/relact/paperdocs.htm

UNESCO. ‘The education of staff and users for the proper handling of archival materials: a RAMP study with guidelines.’

http://www.unesco.org/webworld/ramp/html/r9117e/r9117e00.htm