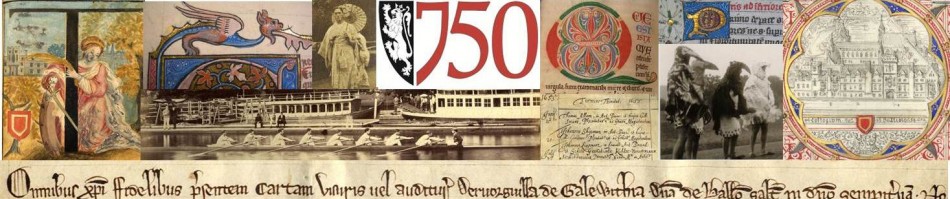

Unlocking Archives talk TT18

Against ‘Iberic Crudity’:

Balliol MS 238E, Bodleian MS Douce 204,

and Laurentius Dyamas

Anna Espínola Lynn, MSt in History of Art and Visual Culture (Wadham College, Oxford), will be speaking on the transmission of style in fifteenth-century Catalan manuscript production.

All welcome! Feel free to bring your lunch. The talk will last about half an hour, to allow time for questions and discussion afterwards, and a closer look at the Balliol manuscript discussed.

Online images of Balliol MS 238E and of Bodleian MS Douce 204

Unlocking Archives is an interdisciplinary graduate seminar series of illustrated lunchtime talks about current research in Balliol College’s historic collections: archives, manuscripts and early printed books, and the connections between them.

Talks take place at 1pm in Balliol’s Historic Collections Centre in St Cross Church, Holywell. St Cross is next door to Holywell Manor and across the road from the English & Law faculties on Manor Road; directions http://archives.balliol.ox.ac.uk/Services/visit.asp#f.

Questions? anna.sander@balliol.ox.ac.uk.

Stanford in Oxford at Balliol

Last week I had the privilege and huge fun of planning and teaching a class with Stephanie Solywoda, Director of the Stanford Program in Oxford. We were talking about medieval Oxford – town, gown and especially books…

Stanford people get up close and personal with medieval manuscripts – here we are discussing the complicated layout of this Aristotle manuscript, and the functions of illuminated initials other than just being amazing – navigation, mnemonics, sometimes didactic or humorous (or even inexplicable) comment on the main text.

Colours and lines are still bright and sharp after 7 or 8 centuries – it’s hard to imagine someone spending the weeks or months it would have taken to copy this text out by hand. Not to mention manually justifying every line while keeping letter spacing consistent, using abbreviations and having to allow for imperfections in the parchment interrupting the writing space.

Bindings on the other hand, may not last so well – note the spine break in the manuscript above.

Old books, new technology – online gateway to Parker on the Web, and a modern facsimile of the ancient Book of Kells that lets us safely handle a binding using medieval techniques.

Kells facsimile – not strictly related to Balliol’s special collections (alas, no early Irish manuscripts here) but a facsimile is a wonderful teaching resource. The pages feel like the modern shiny light card they are, but they faithfully reproduce weight and thickness of parchment, dirty smudges at the edges, the way some fugitive pigments show through to the other side of a page (e.g. lower right of this opening) and even the holes in the original. These Stanford students will be visiting the real Book of Kells, the centrpiece of a dedicated exhibition, at Trinity College Dublin later in their time in the UK, so this was particularly apposite.

Some recently conserved administrative documents from Balliol’s history, contemporary to the books displayed, were on show to demonstrate the differences in layout, hands and contents between academic texts and legal records.

Balliol’s Foundation Statutes of 1282, still with the original seal of Dervorguilla de Balliol, in their new mount and box from OCC. Like nearly all legal documents of the time, this is in formulaic, heavily abbreviated medieval Latin, but we were able to find the word ‘Balliol’ in several places in the text (and a full transcription and translation was available 😉 ) We talked about the evolution of early college statutes, the similarities and differences between colleges and monastic houses, the heavily religious language of the statutes and the practical stipulations included.

Balliol’s historic seal matrices and modern impressions – all featuring female figures, like the foundation statutes. St Catherine is the College’s patron saint, and we talked about the college chapel system and the fact that Balliol had a side chapel dedicated to St Catherine in St Mary Magdalen church – just outside Balliol’s walls – before it received permission (and had the funds) to build its own chapel.

Another beautifully mounted document, two copies of the Bishop of Lincoln’s permission to Balliol College to build its own chapel.

An opening from the first Register of College Meeting Minutes (1593-1594) showing formal but more workaday recordkeeping in the College, still in Latin but often with English phrases or sections, annotations, amendments and crossed out sections.

MS 301 has a typical layout for legal and Biblical manuscripts, with a central section, here decorated, of the main text to be studied in larger hand, and surrounding layer or layers of formal commentary plus shorter notes and personal reader annotations toward the outer edges. (No, the book is not hanging over the edge of the table – it’s the camera angle!)

Details of the decoration in that central section, showing rubrics (headings in red), regular red and blue penwork initials and still-familiar paragraph/section marks, plus more pigments, white highlights, and gold leaf on the most important initial.

A plainer study text, made for university use and leaving plenty of room for commentary and annotations to be added.

We enjoyed these whimsical doodles, turning initials into faces so full of character they might be portraits – or caricatures. They may also have had mnemonic and navigational value, particularly in a manuscript without folio numbers, as was usual. The manuscripts are foliated now, but most foliation is either early modern and/or 20th century.

The oldest document (ca. 1200) in the College Archives has been mounted to allow it to be displayed without damaging it; I also had two C14 legal documents out for the students to handle, and so we could talk about seals, seal attachment, and pre-signature authentication methods.

A mounted charter with pendent seals, still with their green and red silk cords intact. The conservators’ inner box cover includes photographs of the reverse of the whole document, the seal and the label, as well as a caption. Instant display without having to disturb a fragile manuscript.

For extra resources and further reading, I had a small selection of the College’s modern printed books on archives and manuscript studies topics out as well. The Manuscript Book compendium has recently been translated from Italian and is a brilliant resource for eastern as well as western manuscripts.

Links to relevant projects:

- Stanford Libraries: Parker Library on the Web

- British Library: Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts – virtual exhibitions

- Huntington Library: Manuscripts collections

- Balliol College: Manuscript images on Flickr

- Bodleian Libraries: Digital.Bodleian

- Cambridge: MINIARE

- Trinity College, Dublin: the Book of Kells

- Chester Beatty Library, Dublin – images

antechapel display – winter Vacation 2017

A selection of images from the Michaelmas exhibition of medieval manuscripts at St Cross is now on public view in the antechapel in Broad Street:

#mss2017 Introduction

Introduction

I have produced numerous small displays of medieval manuscripts for teaching and college events since I became responsible for the collection and moved it to the new premises in 2010-11, but this is the first major exhibition of Balliol’s western medieval manuscripts in the Historic Collections Centre at St Cross Church. It may even be the first exhibition of this collection that has been open to the public.

Because it’s rare for these ancient, unique and delicate objects to be exhibited, even to members of the College, I wanted to show as large a selection as possible, and to provide a broad overview of the collection. I have included manuscripts from the whole medieval period covered by Balliol’s collection (C11-16), representing a range of provenances, decoration and handwriting styles, contents, sizes, formats, physical condition, and conservation issues. Exceptions prove the rule; not everything in the exhibition is medieval, western or a codex (book-shaped) – or even manuscript (handwritten). Two manuscripts are shown closed; one is displayed upside down. Some mss are well known to scholarship and have been exhibited before; others are relatively unknown. All are catalogued (1-450 by RAB Mynors, 1963), but to widely varying degrees of detail and emphasis. Visitors may be surprised by the variation in the amount of documentation about not only conservation work but provenance and donation.

Focusing on the theme of damage and conservation removed possible restraints of e.g. period or subject, while avoiding a miscellaneous ‘Treasures of…’ approach. The manuscripts’ move to new premises was a good point in their history to assess their current condition and their needs for the foreseeable future, continuing to build on Balliol’s first several years as members of the Oxford Conservation Consortium.

Damage to manuscripts can occur at any stage of their existence – during production, while in storage, and in use (both voluntary and involuntary). I need only quote from the litany of woes turned up in the 2014 condition survey: dirt, losses, pest damage, staining, ink corrosion, text loss due to trimming, water damage, cockling, pleating, old repairs, smudging, ink fading/abrasion, ink offset, flaking gold, tears – to name a few. ‘Losses’ is a particularly painful catchall term including anything from a torn away corner to an excised illuminated initial to whole missing pages.

Conservators plan and carry out repairs to these amazing objects with great professional skill and enormous patience. Similar problems come up again and again, yet every case has to be treated individually, combining scientific understanding, practical knowledge and a creative approach. Much of their work is hidden inside a book’s binding once treatment is complete. Most items are not intended to, and do not, look ‘like new again’ after repair; they show their old scars as part of their material history, but are made safe to handle again (carefully) without causing immediate further damage.

In addition to repairs, however, the conservation team also help their members with advice and support on a wealth of related subjects: pest and environmental monitoring, preservation materials, all aspects of exhibition production, borrowing and loan of objects, transport, general and specialised handling and cleaning training for staff, loan of specialist equipment and advice on purchase, disaster preparedness and emergency response planning and training, and as we all do, career advice and visits for students.

Not every manuscript shown has been conserved – or at least not to modern standards – yet. The exhibition features a number of fine examples of the work of the Oxford Conservation Consortium and previous conservators known and unknown, but it marks a milestone rather than an endpoint. The OCC has been providing conservation services to Oxford’s special collections since 1990. Balliol joined it in 2006 at the instigation of Dr Penelope Bulloch, then Fellow Librarian, and with support from John Phillips and the Balliol Society. The OCC became an independent charity in 2014, and Balliol’s Archivist and Finance Bursar sit on its management committee. The OCC now cares for the historic collections of 17 colleges. They also maintain the Chantry Library of conservation-related publications, which is available to everyone.

A great advantage of OCC membership is the ability to plan not only a full year’s work but strategies and priorities for years to come. We have been able to move from a reactive programme of occasional work on individual manuscripts to proactive long-term planning that includes detailed conservation of key individual items but emphasises improving the condition and care of the collection as a whole.

Curatorial initiatives for the medieval manuscripts comprise a network of related projects:

Completed:

- 2014 condition survey

- boxing of all manuscripts (nearly 100) previously without boxes

- 2017 exhibition

Ongoing:

- Conservation treatment/repairs

- Replacement of old/worn/substandard boxes

- Improving descriptions and updating bibliography

- Digitisation for documentation & research

- Supporting teaching and research in person

- Documenting manuscript fragments in early printed books

- Workshops on correct handling of special collections material for students preparing for research using archives and manuscripts

The aim of all of these activities, and others as yet in the planning stages, is to improve preservation and access for all the manuscripts.

Preservation means ensuring the continued survival, and improved physical condition, care and handling of, all manuscripts. This is the responsibility of all staff and users of material. An archivist’s regular preservation tasks may include removal of rusty paperclips and staples, rehousing in acid-free archival quality folders and boxes, photography and scanning for cataloguing (to minimize use of the original), and training students and researchers in good handling practice.

Access is not only hands-on consultation of original material, but also improved access to better information about the manuscripts; images are an important source of information. It also includes improving understanding of the manuscripts as texts, physical objects and cultural products. Access is provided by staff and institutions, with input from researchers and scholarly publication.

Conservation means specialist professional treatment and repair of individual manuscripts, with the aim of ensuring that future careful handling/consultation/display does not actively cause further damage. Work is planned by staff in consultation with conservators, and carried out by the conservators.

Each of the manuscripts displayed is augmented by a number of prints from digital photographs, mostly enlarged details. While no facsimile edition or digital image can replace direct encounters with original manuscripts, they can support and augment research in person. An exhibition can only show one opening of a codex, or (usually) one side of an original document, at a time, in a single geographical place, to a limited number of people, for a limited period of time. Digital images can help to provide more access to information about, and contained within, the manuscripts, to more people in more places over a longer period. [more about digital images as tools for manuscript studies – not as substitutes for the original]

Digital photography of the manuscripts is carried out as part of my work as archivist, prioritised by researchers’ enquiries. Depending on the request and time available, I may photograph all or part of the manuscript, though in the case of part photography, ideally I will return later to complete the set. Images are sent to individual enquirers for ease of download, and also posted to Flickr at full resolution. Neither the original requester nor online users are charged for access to the images; widening access in practicable ways to collections that cannot be made generally available in person is part of the College’s obligations as a Charity, and of its aims as a higher education institution responsible for these historic collections. So far I have posted images of more than 100 of the medieval manuscripts online, many of them complete, in addition to some of the archives, personal papers, and key research resources, and the Balliol Flickr collections have had more than 2.5M views altogether (as of October 2017).

The supplementary images in each display case provide a window into other parts of the book and a magnified view of tiny details that can be hard to appreciate with the naked eye. If you are inspired by the original manuscripts on display to explore the wider world of manuscript studies, links to more images of these and many more of Balliol’s medieval manuscripts, and a starter list of print and online sources, are provided in the Further Reading post.

A note about display: I have chosen to display most of the manuscripts exhibited on the grey foam wedge supports we routinely use in the searchroom, with the pages in many cases held in place by fabric-covered lead pellets (known as ‘snakes’). Using ordinary supports shows a little of how we, curators and researchers, work with manuscripts; it looks less ‘produced’ than museum-style stands, but after all the collection is owned by a small institution and a very small department. Only a few sets are new for the exhibition, and all will be used after it. This saves huge amounts of specialist time, money and materials in making custom-fitted card or acrylic stands for each, and means that all the display materials will be used again for years to come, for research, teaching and future exhibitions, since the wedge sets can be used in interchangeable combinations to suit the size and opening angle of any volume. Only the four tiny books in case 9 needed their own stands made, as they had to be strapped into place to remain open.

I have also chosen not to print copies of the exhibition catalogue except for use while visiting in person; those who would like a hard copy are welcome to print the PDF version or any combination of the blog posts for their own use. Any exhibition of physical items is ephemeral, but a catalogue should have the lasting effect of opening the exhibits, though in an inevitably limited way, to a wider audience than could possibly attend the exhibition itself. An online catalogue can be accessed and printed at any time according to the needs of the user, and can also be augmented and corrected into the future.

I would like to thank Jane Eagan and her team of dedicated professional conservators at the Oxford Conservation Consortium for a decade of not only repairs to Balliol’s archives and manuscripts, and latterly to some of the early printed books as well, but also for their expert advice and support on all aspects of the material wellbeing of the historic collections, including environmental monitoring and amelioration, pest monitoring and treatment, local and international loans and exhibitions, project grant applications and planning.

I thank also Annaliese Griffiss for proof reading – all remaining errors are mine – and invaluable help preparing the exhibition, as well as her ongoing work on the Manuscript Fragments project, and Sian Witherden for good conversations about tiny books and for her contribution on book vandalism.

– Anna Sander, BA, MPhil, MScEcon, Archivist & Curator of Manuscripts, Balliol College

Photographs in this catalogue are by Anna Sander for Balliol College except where otherwise indicated.

The catalogue as printed for use by visitors to the exhibition is available as a PDF here. The print version is restricted to a single opening (one A4 double-page spread) per manuscript, which is as much as anybody can stand to read while walking round an exhibition; this online version, a series of blog posts tagged #mss2017, contains more detail and more images for most entries, as well as Further Reading sections for specific topics not included in the more general Further Reading post. The print version entries will also be used as Special Collections in Focus posters in Balliol Library and Holywell Manor during Michaelmas Term 2017.

#mss2017 Case 14: MS 384

MS 384, open to full page miniature of the martyrdom of St Thomas à Becket

MS 384, open to full page miniature of the martyrdom of St Thomas à Becket

MS 384 is a 15th century Flemish Book of Hours, made in the Low Countries for the English market according to the Use of Sarum. I am sometimes asked about the pre-Reformation liturgical books lost from the College chapel. Books of Hours would not have been among them – they were designed for the private devotions of secular individuals at home.

It is not known who gave the book to the College, or when, but from a note inside it, it was not at Balliol before the 18th century. It bears marks of having been a much-used family devotional book, and has a remarkable history ( or at least legend) of preservation against the odds; the anonymous donor writes: ‘The Book was found in the thatch of an old house… now my guess is that at the beginning of the Reformation, this Book was committed to Atkins of Weston to be secured ‘till a turn might happen… Pray Sir my humble service to Mr Harris and all friends at Colledge.’

MS 384 does corroborate this story in several ways: there is rather heavy, ingrained dirt across all surfaces, which would fit with its having been stored in the inevitably smoky thatch of a house. Burn marks on its lower edge might indicate a thatch fire – perhaps this is how it was rediscovered. It shows a few signs of contact with water, and of damp conditions. Otherwise, it is in remarkably good condition – it was rebound, probably in the 18th century, but does not show much evidence of earlier intervention in the text block. The only essential repair needed in 2017 was to secure a long tear across the lower part of f.70. unusually, this tear did not start at the edge of a page; rather, it looks as though a guideline ruled with a dry point may have (after several centuries) weakened an already thin and fragile area of parchment.

MS 384 – L, detail of miniature damaged by devotional kissing; R, rather dirty liquid damage from head edge

The other type of damage evident in this manuscript affects two miniatures, with similar partial removal of the faces of the central figures. Such damage to saints’ images, and sometimes to the associated texts, has often been assumed to be deliberate ‘de-face-ment’ by anti-Catholic reformers – but Kathryn Rudy and others have more recently asserted, with excellent evidence, that some such instances are the result of devotional kissing. Both Thomas à Becket (a frequent victim of the deliberate type of damage) and John the Baptist have suffered loss of paint here, but not of drawing or parchment surface – the painting has not been scratched or scraped, neither text nor image has been struck through, and the faces are still clear despite the smudging. Both also look as though the damaged areas have been somewhat damp. Viewers may draw their own conclusions!

work on MS 384 by Celia Withycombe of OCC: fine bridges of Japanese paper connect the edges of an irregular tear, 2017.

More about devotional damage in manuscripts:

- John Lowden, Manuscripts tour ‘Treasures known and unknown in the British Library’ – Kissing Images section

- Kathryn M. Rudy, “Dirty Books: Quantifying Patterns of Use in Medieval Manuscripts Using a Densitometer,” Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art 2:1-2 (Summer 2010) DOI: 10.5092/jhna.2010.2.1.1

More about defacement of images of Thomas of Canterbury (Thomas Becket):

- Sarah J Biggs, ‘Erasing Becket,’ British Library Medieval Manuscripts Blog, 2011.

- Cambridge University Library, ‘The Face Defaced,’ Bodily Memory section of Remembering the Reformation exhibition, 2009-2017. Individual author unidentified.

#mss2017 Case 3b: MS 350

MS350 opening ff 11v-12r (Herefordshire Domesday)

This manuscript of 170 folios includes three separate texts on Anglo-Norman legal subjects: a late 12th c copy of the Herefordshire section of Domesday book (first written in the late 11th c); an early 13th c copy of the earliest treatise on English common law ‘Treatise on the laws and customs of the kingdom of England in the time of King Henry II’, known simply as ‘Glanvill’ after its late 12th c author; and an early 14th c copy of ‘Britton’, the earliest summary of English law to be written in French, probably in the late 13th century. The first two texts are in Latin – with an Anglo-Norman French charm against snake bites appended to the end of the Domesday extract – and ‘Britton’ is in Anglo-Norman French. From the Herefordshire connection, Mynors thinks it likely to have been another gift to the College from George Coningesby, but there is no internal or external provenance documentation.

MS 350 is displayed open to ff. 11v-12r, part of the Herefordshire Domesday, with entries for the Wormelow and Elsdon hundreds. This opening shows surface dirt, particularly in channels from the head edge, liquid staining at the edges, and ink oxidation of the red initials – most have darkened from bright orange-red to silvery purple. Some of the red and green ink, though not blue, has come through from the verso. The manuscript was rebound, or at least recovered in white vellum (calf skin) in 1892, but this rebinding may have reused medieval wooden boards – it is impossible to tell from the outside. The manuscript is in generally good condition, and only needs some surface cleaning and repairs to the split parchment cover.

The ‘Glanvill’ text in MS 350 is heavily decorated with intricate penwork initials, but no other colours are used and there is no gold. Penwork decoration, the most common form of textual ornamentation in medieval manuscripts, is often done by the main scribe; in this case, the rubrics, red ink chapter headings/incipits/explicits both within the text and in the margins, seem to have been completed along with the main text, while the red and blue initial letters and exuberant decorative penwork were done later and perhaps by another hand. NB the different hues of red ink used, a darker red for the rubrics and a brighter orange red for the initials and decoration. The penwork of the initials Q (Quandoque) and U (Utroque) lace together in alternating colours, and in two places the rubrics and decorative flourishes run across each other.

The margins of this text are home to a good number and variety of lively penwork beasts and human faces many more than the lion, rabbit, goat and dragon featured here. Some grow out of the flourishes of initials, while others are separate figures, mostly in the lower margin, reaching up to feed on the red and blue foliage, and sometimes fruit. As is usual, though not universal, marginal figures appear without comment and seem unrelated to the text, though close study (anyone?) might reveal puns and wordplay – often decoration is (at least) a navigational tool and a memory aid.

More about the texts in this manuscript

- Domesday: online exhibition from The National Archives http://bit.ly/2hw6xRq. The Herefordshire section of Domesday as found in this manuscript was edited by VH Galbraith and J Tait as Heredfordshire Domesday, circa 1160-1170 (Pipe Roll Society, London 1950).

- Glanvill: explore http://www.earlyenglishlaws.ac.uk/

- Britton: HL Carson, ‘A Plea for the Study of Britton’ (1914) http://bit.ly/2huYfZK

- Anglo-Norman French language: hub for all things A-N http://www.anglo-norman.net/

- John Hudson, The Formation of the English Common Law: Law and Society in England from King Alfred to Magna Carta (Routledge, 2nd ed 2017) – a briefer distillation of his weightier tome on the subject, The Oxford History of the Laws of England (OUP, 2012).

MS 350 full set of images: http://bit.ly/2hsx9Fu

#mss2017 Case 9: tiny books, tiny writing

Sian Witherden has been working on tiny books as part of her Balliol DPhil research. She writes: ‘In this exhibition, four small Balliol manuscripts have been placed together in one display case. These books are not related to each other in any way besides their common size—they contain different texts, they are written in a variety of languages, and they hail from across the globe. However, the creators of all these books faced the same challenge: how do you produce a readable text on such a small scale? Each of these books is smaller than an adult’s hand, and this demands an impressive level of craftsmanship. In MS 348, for example, the scribe has managed to write letters that are just a millimetre or two in height. Creating ornamental initials and illuminations on this scale is an equally arduous task, and close-up photographs of these decorations reveals an astonishing level of detail and precision. ‘

Anna Sander: On the one hand, small books are easy to move, hide or pack away if necessary; not obviously useful for recycling as binding waste, as big sheets of parchment are, when no longer e.g. liturgically relevant; and often much-loved, beautiful, and highly personal items handed down through generations. On the other, they are easily misplaced, lost or stolen owing to their small size; highly attractive on the market, reluctant though an owner might be to sell; and rather chunky to handle because of their high proportion of height and width to thickness. Mechanically, their own weight will not help to ‘persuade’ a stiff binding to open further, and in this exhibition, it’s only the tiny books that need to be strapped in place in order to keep them open. They are made to be held in the hand, or perhaps both hands, used by one person. While big books are necessarily at the more expensive end of the book production scale because of the larger amount of parchment required to make them, tiny books are not necessarily less expensive, as they may be beautifully produced and highly decorated with expensive materials, and are sometimes written on very thin parchment which must have been even more difficult to make than regular sheep or calf.

The size of the text in these small books varies widely – while MS 348’s minute writing is closest in size to that of MS 148, a much larger book, that of the other three small books shown here is not especially small, and reasonably friendly to the naked reading eye. Though it’s especially striking to see a whole book in minute writing, tiny script is not unusual in manuscripts – it is often used for annotations, marginal comments, rubricator’s notes, and interlinear glosses (see e.g. MS 253). Was it done with the same pen as the larger main text? a tiny quill? a feather? a tiny brush? Did they have spectacles or magnifying glasses? There isn’t much evidence – descriptions and depictions of scriptoria and scribes’ equipment and practice are surprisingly few, and not always reliable. We are intrigued, and will add more evidence here as we find it.

More about tiny manuscript books

- J Weston, ‘Teeny Tiny Medieval Books,’ Medieval Fragments blog, December 2013

- L Miolo and A Hudson, ‘Size Matters,’ British Library Medieval blog, May 2016

#mss2017 Case 9d: MS 378

MS 378, open at ff.28-29, showing rubrics and stitching in the middle of a quire

MS 378, open at ff.28-29, showing rubrics and stitching in the middle of a quire

MS 378 is an undated volume of prayers to the Virgin Mary in Ethiopic, or Ge’ez, the liturgical language of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church. This is Balliol’s smallest manuscript book at only 2 ½ x 3 ½”, or 62 x 83mm. It is so tiny that its custom-made box is about four times the size of the book, with a recessed mount to hold it securely. One benefit of this rather larger and heavier box is that it’s easy to find on the shelf, to handle, and to keep track of during production and consultation – a box as small as the book might easily be hidden behind a larger one, or worse, dropped.

This manuscript is displayed closed in order to show its Ethiopic sewing, often known as Coptic style and distinct from later western binding techniques. The Copts, early Egyptian Christians, were the first to use the codex format, and their sewing method is still unsurpassed in simplicity and flexibility: a new Coptic binding can be opened a full 360 degrees.

The MS is in fairly good condition; the sewing is fragile and there is evidence of fairly recent repair to the attachment of the front board – what looks like a large stitch on the lower front cover – but other than some surface dirt it does not require further intervention. The paper label glued to the front cover, which MS 378 has in common with many of the others, is in the hand of EV Quinn, who began at Balliol as Assistant Librarian in 1940 and became Fellow Librarian in 1963, a post he held until 1982.

MS 378 is the only one in the collection known to have been given to the College by Benjamin Jowett from his own library, but there is no documentation in the archives about how he came to acquire it, or its previous provenance.

Although it is neither western nor medieval (as far as we know, at least), this manuscript has been included in the exhibition for two reasons: it shares many of the same conservation issues and endearing qualities as any tiny book, and it serves as a small signpost to another section of the collection that has hitherto suffered from lack of attention. As yet, many of Balliol’s 33 non-western manuscripts are still ‘closed books’: not yet accurately dated and without full descriptions of their contents, they have not been studied in detail and their research value has yet to be assessed. We hope that through recently established Balliol and Oxford contacts, and with good digital images emerging as useful tools, scholars in the relevant fields will soon be able to tell the College more about this part of the collection. Their entries in Mynors’ catalogue have been grouped together under their traditional label of ‘oriental manuscripts’ here.

MS 378, showing stitching, boards and binding

More about Ethiopic manuscripts and Ethiopic/Coptic sewing:

- Ethiopic Manuscripts Collections guide, Princeton University Library

- C Breay, ‘Getting under the covers of the St Cuthbert Gospel‘, British Library Medieval blog (2015) and images of the binding of the Cuthbert Gospel

- S Winslow, Ethiopic Manuscript Production (2011 exhibition, University of Toronto)

- Turning the Pages presentation of an illustrated Ethiopian Bible, British Library

#mss2017 Case 3a: MS 349

MS 349 medieval binding, showing spine and front cover – formerly red

We have begun with two examples of administrative documents created in the course of College business. MS 349 perhaps conforms more closely to the expected type of a medieval manuscript: in codex format, a 15th century copy on parchment, in several different English bookhands, of nine texts related to the office of priesthood, listed by Mynors.

This manuscript is, unusually, displayed closed in order to show the only surviving medieval binding in Balliol’s collection – and a modern gummed paper label in the unmistakable hand of EV Quinn, whose career in Balliol Library spanned 40 years in the 1940s-80s. Images are displayed to show a typical opening, some of the alum tawed supports showing through in places, and an illuminated initial using gold and colour.

MS 349 was bequeathed to Balliol by Dr George Coningesby (1692/3-1768, Balliol 1739) in 1768, and by then would have been an antiquarian gift rather than a contribution to the active contemporary College Library. Coningesby is the largest single donor of manuscripts (17 or 18) to the College after William Gray, a 15th century Bishop of Ely. He also left a large number of printed books to Balliol. Coningesby’s donations were just late enough to escape the wholesale rebinding of the medieval library in 1724-7, for which one Ned Doe was paid nearly £50. Most of the manuscripts are still bound in this 18th century half-calf (similar to suede); the bindings tend to be heavily glued and many have cracked and split, while the fuzzy covers are thin, and tear easily. MS 349’s boards still retain the metal furniture for an otherwise lost fore-edge clasp, but do not bear marks of any chain staple. Mynors notes that ‘The last mention of chaining in the library accounts falls in the year 1767-8, and an entry under 1791-2 ‘From Stone the Smith for old iron and brass’ probably marks the ending of the practice altogether.’

MS 349 – turnin showing something of the cover’s original bright red colour

Losses to the cover of MS 349 reveal a bevelled edge of the wooden board; there is also (old and inactive) woodworm damage, and the smooth pigskin cover has faded from its medieval red nearly back to the original pale brown, though an inner corner shows some remaining dye. While in many cases medieval sewing structures may survive within later rebindings, they are difficult to observe; full medieval bindings are rarer survivals and provide useful research opportunities.

edge of wooden board showing old insect damage

broken sewing supports, exposed within the volume

broken sewing supports, exposed within the volume

At some time there has been a modern repair of ff.121-122, a bifolium that had become detached from the textblock. Although there is some heavy cockling to folios at either end, and tears to spine folds in places, the book opens well and can be handled, carefully.

MS 349 – a typical opening

More about western medieval bindings:

- The Making of a Medieval Manuscript – Getty Museum, 2003

- Bindings section of Medieval Books, University of Nottingham

- Medieval & Early Modern Manuscripts: bookbinding terms, materials, methods and models, Yale University Library Conservation Department, 2015 [PDF]

- Shailor, B. The Medieval Book: Illustrated from the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. University of Toronto Press, 1991.

- Szirmai, JA. The Archaeology of Medieval Bookbinding. Ashgate, 1999, reissued 2016.

and see also resources under Medieval Manuscripts – Introduction on the Further Reading page

#mss2017 Case 1: Statutes of Dervorguilla, 1282.

College Archives D.4.1

Detail of the beginning of the Statutes: ‘Deruorgulla de Galwedia domina de Balliolo…’

We begin not with a codex but with a single sheet of parchment with a pendent seal, the usual format for individual medieval legal and administrative records. This is the first formal document laying out the constitution, governance and way of life of the scholars of Balliol College; it is issued in the name of Dervorguilla of Galloway, Lady de Balliol, and is dated at Botel (Buittle Castle, seat of the lords of Galloway, near the town of Dalbeattie in Dumfries & Galloway), on the octave of the Assumption of the glorious Virgin Mary (i.e. 22 August), in the year of grace 1282. The text is written, as usual for medieval charters and books alike, in heavily abbreviated Latin: in the first line above, ‘dna’ with a line above it is an abbreviation of ‘domina’, ‘lady’; ‘dilcis’ of ‘dilectis,’ ‘beloved’; ‘xro’ of ‘christo,’ ‘Christ’; etc. Some abbreviations are indicated by generic signs including a line above the remaining letters, or the apostrophe still used today, but many are systematically represented by specific characters or symbols: in the fourth line above, you will notice several words ending in ibȝ – the ȝ, which looks like the Middle English letter yogh or a long-tailed z, stands for -us, so the ending is -ibus, used in Latin for dative or ablative plurals. There are useful lists and dictionaries of medieval abbreviations, but any archivist or researcher who routinely deals with medieval documents memorizes the most frequently used ones. Understanding the generic abbreviations depends on good reading ability and a knowledge of the formulaic language and context-specific vocabulary used in the relevant form of medieval documents.

Statutes of 1282, face (front side) and dorse (back side). Photos by OCC, 2017.

The Statutes have required remarkably little repair over their 735 years and are still in extremely good condition: as the College’s key founding document they have always been carefully preserved, and as they were legally superseded by Sir Philip Somervyle’s statutes in 1340 they were not current for long enough to suffer much wear from actual use. Parchment, usually made from the prepared skin of sheep or young calves, can last longer than a millennium if kept away from heat, damp, direct sunlight and pests; iron gall ink if made correctly and similarly preserved lasts as well. The fate of wax seals is often less happy, as in addition to the vulnerabilities already mentioned, they are naturally highly brittle and fragile even under the best storage conditions.

This document will have been folded around its seal for much of its existence; this has helped to preserve both the text and the seal. It and many of the medieval title deeds were flattened, and a modern label affixed, in the late 19th century. The original fold lines are still readily visible.

The Statutes were mounted in an acid-free buffered housing inside a Perspex box frame by Judy Segall of the Bodleian Library’s Conservation Department in 1986, at the instance of Dr JH Jones, then Dean and Fellow Archivist of Balliol. This treatment protected the flattened document and its seal, and made it safe to produce for either research or College events.

1282 Statutes, 1986 mount showing silica gel desiccant crystals. Photo by OCC, 2017.

In 2017, Dervorguilla’s Statutes were lightly cleaned and rehoused in a new acid-free mount by Katerina Powell of OCC, with an outer box made by Bridget Mitchell of Arca Preservation.

Seal of Dervorguilla: L obverse (front), R reverse (back). Photos by OCC, 2017.

The seal attached to the 1282 Statutes is not the College seal but the personal seal of Dervorguilla herself. In her right hand she holds an escutcheon (shield) bearing the orle (shield outline shape) of the Balliol family; on the left, the lion of Galloway. The other two shields represent Dervorguilla’s powerful English family connections: on the left, three garbs (wheatsheaves) for the Earl of Chester; and on the right, two piles (wedges) meeting toward the base for the Earl of Huntingdon. The motto on the obverse (front) reads, clockwise from the top: + S’[IGILLUM] + DERVORGILLE DE BALLIOL FILIE ALANI DE GALEWAD’.’ [Seal of Dervorguilla de Balliol, daughter of Alan of Galloway.’] That on the reverse (back) gives her titles in reverse: ‘S’ DERVORGILLE DE GALEWAD’ DNE DE BALLIOLO’ [Seal of Dervorguilla of Galloway, Lady de Balliol].

The College’s shield, used in its official logo today and visible in various forms throughout the College site in Broad Street, is taken directly from that shown on the reverse of Dervorguilla’s seal, above: the arms of Balliol and Galloway impaled, with, unusually, those of the wife rather than the husband on the dominant dexter side – the right as held, though the left as viewed.

Further reading:

- F de Paravicini, Early History of Balliol College. 1891. (includes full transcript of Statutes, in Latin) online at archive.org

- HE Salter, The Oxford Deeds of Balliol College. 1913. online at archive.org

- Marjorie Drexler, ‘Dervorguilla of Galloway.’ Transactions of the Dumfriesshire and Galloway Natural History and Antiquarian Society LXXIX (3rd series) 2005, pp.101-146.

- JH Jones, A History of Balliol College. 2nd ed rev, 2005. (includes full English translation of Statutes)

- Two illustrated talks on the conservation of medieval charters and their seals by Martin Strebel of Atelier Strebel, presented at the Seal Conservation Round Table Congress Oxford, March 2007

- Amanda Beam. The Balliol Dynasty: 1210-1364. John Donald, 2008

- National Library of Wales, Seals in medieval Wales

- Imprint Project: a forensic and historical investigation of fingerprints on medieval seals, University of Lincoln

Manuscript Fragments in Early Printed Books

a selection of manuscript fragments inside Balliol’s early printed books

a selection of manuscript fragments inside Balliol’s early printed books

Balliol’s archivist and librarians are working together with researchers to collect information about manuscript fragments reused in the bindings of the college’s early printed books. This information has not been compiled at Balliol before, and while some manuscript fragments are well known in secondary literature, the college’s catalogue entries do not always include copy-specific details describing them – or even indicating their presence.

Fragments are usually located just inside the front and/or back covers of books, may consist of paper or parchment, and can occur as spine linings, stubs, pastedowns, tabs, and flyleaves – or even offsets, inky ghosts of vanished texts left on the facing page. All kinds of texts are reused; so far we have already noted full or nearly full pages of text, decorated, decorated initials, sections of medieval and early modern music notation, and parts of administrative documents and personal letters.

More about current research on manuscript fragments and binding waste

- Annaliese Griffiss on her current work on the Balliol project

- Images and descriptions from the ongoing Balliol project

- Beinecke Medieval Fragment and Binding Waste Project , Yale University

- Princeton University Library online exhibition about historic bookbindings, including a section on manuscript binding waste

- Digital Image Archive of Medieval Music (DIAMM)

- Erwin, Micah. “Fragments of Medieval Manuscripts in Printed Books: Crowdsourcing and Cataloging Medieval Manuscript Waste in the Book Collection of the Harry Ransom Center.” Manuscripta 60.2 (2016): 188-247. Brepols. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1484/J.MSS.5.111918

- Fragment identification crowdsourcing project – Harry Ransom Center, UTexas at Austin

- Fragmentarium: International Digital Research Lab for Medieval Manuscript Fragments , University of Fribourg

- Liz at the Beinecke – a graduate student’s Tumblr about bindings and binding waste, Yale University

- Lost Manuscripts – a project led by David Rundle at the Centre for Bibliographical History at the University of Essex, with particularly thorough and useful apparatus

Balliol ARCH C. 1. 9 #mss2017

Guest post by Sian Witherden

Balliol College Library has one copy of the Rudimentum Novitiorum (‘Handbook for Novices’), an encyclopaedia of world history whose author remains anonymous. This book was printed on paper in Lübeck by Lucas Brandis on the 5th of August 1475. The volume is quite large at 380 x 290 mm, and it is still in the original stamped leather binding. Other copies from the same print run are held in libraries across the globe, including Berlin, Copenhagen, Moscow, Paris, Prague, Princeton, Vienna, and Zürich. Each of these copies has its own unique history, but what is perhaps most remarkable about the Balliol copy is the way it has been dismembered by a later reader (or perhaps readers). Many of the woodcut prints in this volume have been cut out, though there seems to be no obvious reason why certain images were selected for excision and not others. Perhaps the reader wanted to keep these particular ones for a scrapbook or put them to use in another volume. Unfortunately, leaves are also missing from both the front and back of the book.

Another reader was evidently so dismayed by the extent of the losses that he felt impelled to make a comment in the margins: “Is it not a great shame to the scholars of Balliol College to suffer such a choice book as this is to be thus defaced?”[1] There is of course a distinct irony to this, as the annotator takes issue with the defacement of the volume while simultaneously adding his own blemishes to the same book.

In the sixteenth century, the book was evidently owned by John Wicham, whose name appears twice on the outer cover along with the year 1584. Curiously, the book is incorrectly identified as the Opus Historicum of Guillerinus de Conchis both on the spine and within a flyleaf note written in “a late sixteenth or seventeenth century hand,” according to Dennis E. Rhodes. The Rudimentum Novitiorum has no connection with Guillerinus de Conchis.

* * *

For further reading on this book, see Dennis E. Rhodes, A Catalogue of Incunabula in all the Libraries of Oxford University outside the Bodleian (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1982), 296–7.

[1] Abbreviations have been silently expanded and orthography has been modernized.

– Sian Witherden, September 2017. Follow Sian’s tweets @sian_witherden

light #mss2017

Light exposure (lux, UV, heat) is always a concern during exhibitions. How much light does St Cross get, and how can ancient manuscripts be protected while also being made accessible to visitors?

First, limiting exposure. Exhibitions of original material run for 3 months maximum. Pages exposed are changed regularly where that’s practical for the topic of the exhibition. Depending on their condition, books are closed whenever open hours are not planned for a few days in a row. Thanks to the condition survey and research following from it, I’m developing a ‘rota’ of manuscripts that can be produced as examples of various features, rather than getting out the old favourites every time.

The interior of St Cross, including the book cases used for exhibitions, does receive a surprising amount of natural as well as artificial light. The clerestory windows on the south side, although they are small and high, allow a lot of light for much of the day on the shelves on the north side of the nave. The above photo is taken with no artificial lighting on at all, around midday in early September. It is clear to see how much more direct sun shines on the upper than the lower shelves.

Thanks to the deep shelving and even deeper pelmets on top of the cases, the back of any shelf receives much less direct sunlight than the front. But manuscripts on display need to be as visible as possible – at the front of the case.

Also at the front of the case are these very bright and undimmable LED lights down both sides – they provide all the ambient light to the working area of the reading room as well as illuminating the objects on the shelves. It would be complicated and expensive to install temporary, movable conservation-standard low-level lighting in all these cases. The LEDs emit practically no heat or UV at all, and their intensity decreases dramatically a few inches away. But they are still pretty bright.

Also at the front of the case are these very bright and undimmable LED lights down both sides – they provide all the ambient light to the working area of the reading room as well as illuminating the objects on the shelves. It would be complicated and expensive to install temporary, movable conservation-standard low-level lighting in all these cases. The LEDs emit practically no heat or UV at all, and their intensity decreases dramatically a few inches away. But they are still pretty bright.

There is a simple and effective, if not ideal, solution: open manuscripts (or indeed closed books, as bindings suffer from sunning as well) are covered with a (new) acid free folder, or similar conservation-quality light card cut to fit, outside of exhibition open hours. This blocks pretty much all the light from sunshine and artificial lighting.

The free-standing exhibition cases are fitted with heavy card covers, which are also in place outside exhibition open hours. These are easier to put on and remove than their usual full-length wooden covers.

The free-standing exhibition cases are fitted with heavy card covers, which are also in place outside exhibition open hours. These are easier to put on and remove than their usual full-length wooden covers.

Medieval Manuscripts: Michaelmas 2017 Exhibition further reading

A tiny sample of sources from a vast field in print and online, examples mostly in English and within the UK. Fortunately in a blog post I am not as limited as in print, and can add as many as I like, so do share your favourites.

Balliol’s Medieval Manuscripts Online

- Digital photographs of more than 150 manuscripts (so far) on Flickr

- RAB Mynors’ Catalogue of the Manuscripts of Balliol College Oxford (1963) with additions, corrections, new bibliography and links to images

- Previous displays, Special Collections in Focus features etc here on the blog

Medieval Manuscripts – Introduction

- Dianne Tillotson’s Medieval Writing site

- Quill by Erik Kwakkel and Giulio Menna

- Medieval Manuscript Manual, Central European University

- The Making of a Medieval Manuscript, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge UK

Palaeography and Diplomatic – reading old handwriting and understanding old documents (medieval & early modern)

- DigiPal – C11 English palaeography

- Dave Postles’ medieval and early modern palaeography training

- English Handwriting 1500-1700 – an online course (Cambridge)

- National Archives – Reading Old Documents resources

- Palaeography Training at Bangor University

- Scottish Handwriting

- Theleme (École des chartes, Paris) – Techniques pour l’Historien en Ligne : Études, Manuels, Exercices, Bibliographies [seulement disponible en français]

- Adfontes (University of Zurich) [nur auf deutsch]

Preservation and Conservation

- Bodleian Libraries Conservation Department (University of Oxford, UK)

- British Library Collection Care (formerly Preservation Advisory Centre, National Preservation Office)

- British Library, Medieval Manuscripts Blog, ‘Look on these works and frown?‘ May 2013, author not identified.

- Institute of Conservation (UK)

- Cornell University Library Conservation Blog

- The C Word – The Conservators’ Podcast

Old Manuscripts, New Science

-

- The Iron Gall Ink Website

- MINIARE Project – Manuscript Illumination: Non-Invasive Analysis, Research & Expertise

- Under Covers: the Art & Science of Book Conservation , UChicago Libraries Preservation Dept

- Digital Editing of Medieval Manuscripts 5 European university partners

- eCodicology – Algorithms for the Automatic Tagging of Medieval Manuscripts

- Old Books New Science Lab at the University of Toronto

Online research collections and exhibitions

- University of Pennsylvania

- Koninklijk Bibliotheek van Nederland

- British Library

- Digital Bodleian, Oxford (under construction 2017)

- Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

Medieval Manuscripts Blogs – Curators & Researchers

- British Library Medieval Manuscripts

- Erik Kwakkel

- David Rundle: Bonae Litterae

Printed Sources – Introduction to Medieval Manuscripts & Book History

- Christopher de Hamel, A History of Illuminated Manuscripts (1994)

- Jane Roberts, Guide to Scripts Used in English Writings Up to 1500 (2005)

- Raymond Clemens & Timothy Graham, Introduction to Manuscript Studies (2007)

- Ralph Hanna, Introducing English Medieval Book History: Manuscripts, Their Producers and Their Readers (2014)

- Alexandra Gillespie & Daniel Wakelin, eds. The Production of Books in England 1350-1500 (2014)

UK Academic & Professional Organisations

- Archives and Records Association (ARA), formerly Society of Archivists

- Association for Manuscripts & Archives in Research Collections

- CILIP Rare Books & Special Collections Group (RBSCG)

Oxford seminars & events

- Centre for the Study of the Book

- Seminar in Palaeography and Manuscript Studies events advertised termly on https://talks.ox.ac.uk

- Oxford Medieval Studies

If you use social media, #medievaltwitter is a lively and useful place to find all kinds of news and discussion of professional and academic issues for and by medievalists, including many of the scholars and institutions listed above. Try hashtags #manuscriptmonday #mondaymonsters #fragmentfriday #flyleaffriday

#mss2017 is open!

This year 308 people visited St Cross Church for Oxford Open Doors, 9-10 September 12-4pm both days. Here’s what they saw… and what you can see too, by making an appointment to visit between now and mid-December.

Watch this space for more public exhibition opening hours advertised later in the term, but individual and group visitors are very welcome almost any time by appointment. Visiting hours are normally Mon-Fri 10-1 and 2-5; appointments aren’t meant to be exclusive, it’s just that the exhibition and reading room are in the same space and we need to plan ahead to ensure that visitors and researchers are here at different times. Please come!

Many thanks to our Oxford Preservation Trust volunteers on both days – they staffed the front desk throughout, welcoming visitors and freeing staff to circulate and answer questions about the building, the conversion project, and the exhibition.

20+ medieval manuscripts on show, and all these people are doing the puzzle… it’s a good one, based on one of the manuscript images. Come and try it!

Start here – in fact the 1588 charter with the curtain is mounted permanently and isn’t part of the current exhibition, but it does fit nicely with its neighbour…

Case 1. College Archives D.4.1 Statutes of Dervorguilla. 1282, in Latin, on parchment. First Statutes of Balliol College, with seal of Dervorguilla de Balliol, Lady of Galloway, co-founder with her husband John de Balliol (d.1269) of the College. Shown in new mount and box, with enlarged images of both sides of Dervorguilla’s personal seal.

Case 2. College Archives Membership 1.1. First Latin Register of College Meeting Minutes 1514-1682, in Latin and English, on paper. Earliest surviving records of Balliol College’s Governing Body. Open at entries for the early 1560s, mostly concerning elections of Fellows at this stage rather than a full range of College business. Shown with images of damage and historic repairs to the last page of the volume, and illuminated medieval liturgical music manuscript reused (upside down) as binding waste.

Case 3.

L: MS 349. 15th century collection of nine texts related to the office of priesthood, in Latin, on parchment. Bequeathed to Balliol by Dr George Coningesby in 1768. Closed to show the only medieval binding in Balliol’s manuscript collection. Displayed with images of the text inside.

R: MS 350. 12th, 13th & 14th centuries, 3 medieval treatises on English law, including Herefordshire section of Domesday. Victorian vellum binding, in Latin and Anglo-Norman French, on parchment. Bequeathed to Balliol by Dr George Coningesby.

Case 4. MS 263 14th-15th century copy of texts on poetic and rhetorical composition, in Latin, on parchment. Rebound 1720s. Provenance unknown. Displayed upside down to show extensive water damage and loss to upper outer corners of the first 100 folios. Currently in unusable condition.

Case 5. MS 238E ca.1445. 5th volume of medieval encyclopedia, Fons Memorabilium Universi, compiled by Dominicus Bandini de Arecio, in Latin, on parchment. Conserved and rebound ?early 2000s. Copy commissioned and given to Balliol by William Gray, student at Balliol ca.1430 and later Bishop of Ely (d.1478).

Case 6. MS 148 2nd half 13th century. ‘Bernardi opuscula’, collection of short texts by 12th century Cistercian theologian and reformer Bernard, Abbot of Clairvaux, in Latin, on parchment. Rebound 1720s. Given to Balliol by William Gray, Bishop of Ely (d. 1478).

Case 7. MS 253 13th century. ‘Logica vetus’ and other texts by Aristotle, in Latin, on parchment. Rebound 1720s. Provenance unknown; late medieval Balliol ownership inscription.

Case 8. MS 12. Ca. 1475. Josephus, Antiquitates Judaicae (History of the Jewish People), in Latin, on parchment. Printed at Lübeck by Lukas Brandis, ca. 1475. Rebound several times, conserved 2010-11. Given to Balliol by William Gray, Bishop of Ely (d. 1478). Not a manuscript! But hand finished and decorated throughout, and mistaken for a manuscript by more than one early cataloguer. It also has a shelfmark as an early printed book, Arch.C.1.6.

And now to the chancel step for a case dedicated to the special issues of using and looking after tiny books…

Case 9.

L: MS 367. 11th century Antidotarium – medical recipes and remedies, in Latin, on parchment. Victorian binding. Probably given to the College by Sir John Conroy, 1st Bt, Fellow of Balliol 1890.

R: MS 348. 13th century Vulgate Bible, in Latin, on very thin parchment. ‘Pocket Bible.’ Rebound 1720s. In Balliol by the 17th century; provenance unknown.

Case 9. cont.

L: MS 451. 1480s. Book of Hours (Use of Rome), perhaps from Ghent or Bruges, in Latin on parchment. Early 19th century binding by by C. Kalthoeber of London. Given to Balliol by the Rev. EF Synge.

R: MS 378 Undated. Prayers to the Virgin Mary, in Ethiopic (Ge’ez), on parchment. Original wooden boards without cover. From the personal library of the Rev. Benjamin Jowett, Master of Balliol 1870-1893, other provenance unknown. This is not western or (as far as we know) medieva, but it’s Balliol’s smallest manuscript codex, and a link to the non-western manuscripts in the collection, most of which are as yet much under-studied.

Case 10. MS 396 Early 14th century. Five leaves of a noted Sarum Breviary, one of the liturgical books used for the Daily Office, in Latin, on parchment. These leaves were found in and removed from the binding of an ‘old dilapidated’ College account book in 1898, by George Parker of the Bodleian Library.

And back to the nave for a case full of medieval title deeds…

Case 11. College Archives E.1. 1320s-1350s. Title deeds relating to property and an advowson at Long Benton (Much/Mickle Benton) near Newcastle, given to Balliol College by Sir Philip Somerville in 1340, in Latin, on parchment, with seals.

Case 12. MS 116, later 13th century. Commentary by Eustratius, an early 12th century bishop of Niceaea, on Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, in Latin, on parchment. Rebound 1720s. At Balliol by the late 14th century; provenance unknown.

Case 13. MS 277, late 13th century. Aristotle’s Metaphysics, and Meteorology, trans. Moerbeke, and Ethics, trans. Grosseteste, in Latin, on parchment. Rebound 1720s. May have been at Balliol in the 14th century, alienated and returned in the 15th; given by Mr Robert Rok (Rook).

Case 14. MS 384 15th century. English Book of Hours according to the Use of Sarum, in Latin, on parchment. 18th century binding. At Balliol since the 18th century; provenance unknown.

Case 15. MS 210 1st half 13th century. Several texts by C12-13 University theologians, in Latin, on parchment. Rebound 1720s. Given to the College by Roger Whelpdale, sometime Fellow of Balliol and Bishop of Carlisle in 1419-20 (d. 1423).

Case 16. MS 173A 12th and 13th century. Two collections of short texts bound together, on medieval music theory, in Latin, on parchment. Rebound 1720s. Given to Balliol by William Gray, Bishop of Ely (d. 1478).

Case 17. College Archives B.22.1, the oldest document in Balliol College’s archives, is an undated charter of ca. 1200, recording a grant of the Church of St. Lawrence-Jewry, London, with rents etc., from Robert, Abbot of St. Sauve, Montreuil, to John de St. Lawrence, with others.

Case 18. MS 354 Early 16th century. Commonplace book of London grocer Richard Hill, in English, Latin and French, on paper. Medieval song or carol texts, literary extracts, poems, religious and spiritual texts, notes on farming and trade, recipes, proverbs, etc. Original limp parchment cover. Provenance unknown.

Case 19. MS 240 12th and 14th centuries. Miscellany of religious texts, in Latin, on parchment. Conserved and rebound by Andrew Honey, 1990s. From the priory of Monks Kirby (Warwickshire). Given to the College by Richard Bole, Archdeacon of Ely (d.1477).

In addition to a wealth of original manuscripts exhibited, there are also several forms of supplementary material – here, a display on loan from OCC with more details about their work for the colleges’ collections – and Balliol items used for three of the four illustrations: B.22.1 above, MS 12 above, and Robert Browning’s DCL gown (awarded 1882). On the right visitors can touch and feel samples of just a few of the materials they use for repairs, e.g. papers and tissue, fabric and thread, parchment and leather.

At levels both lower and higher than the exhibition cases are more images from Balliol’s manuscript, for sheer enjoyment. Above, a much enlarged opening of MS 451, the 15th century Book of Hours; below, two miniatures from MS 383, a much-studied high-status 15th century copy of Ovid’s Heroides ina French verse translation.

The corridors around the sides of the church not only provide access to wall memorials and stained glass but also offer an unusual insight – windows into the climate-controlled repositories where the archives, manuscripts, and early printed books are stored.

With several hundred visitors in a few hours, there is always a queue for the loo during Open Doors – but even here one can enjoy more details of illuminated initials from Balliol manuscripts.

Some of the more than 300 Open Doors 2017 visitors enjoying the building, the manuscripts and a challenging custom jigsaw, based on an image from one of the manuscripts on display.

#mss2017 Case 10: MS 396

Guard-book (hardbound fascicule volume) containing five leaves of an early 14th century noted Sarum Breviary, written in two columns of 28 lines with large red and blue flourished capitals. These leaves were found and removed from the binding of an ‘old dilapidated’ College account book in 1898, by George Parker of the Bodleian Library, who was checking College records on behalf of a Mr Richardson.

In addition to the obvious holes in the parchment, the unknown early C20 conservator observed that the material was damaged and fragile throughout, and applied a then popular method known as silking, or chiffon repair: a fine silk gauze was glued to both sides of the parchment. This was considered less invasive than the other method available at the time, which covered the damaged area with translucent paper.

Detail of MS 396, darkened and contrast enhanced to show layers of silking – more visible where the parchment has been lost, but present over both sides of the full page.

Silking certainly reinforced the parchment while leaving the text and music largely visible from both sides, but it is hard to tell now how much of the brown discoloration may have been caused by the adhesives used in the silking process. The glue still gives off a distinct smell, but it would cause more damage to the leaves now to remove the silking than to leave it in place. The leaves are reasonably safe to consult as they are, so no further intervention will be made for now.

A breviary is one of the liturgical books used for the Office, the cycle of daily church services other than the Mass. It includes the text and musical notation, shown here in square black notes, known as neumes, on a red four-line stave. A direct descendant of this system, which indicates mode, pitch and relative note length, is still used for traditional Gregorian chant. Are these manuscript fragments related to any of the other pieces of liturgical manuscript recycled as binding waste in Balliol’s administrative records and early printed books, or elsewhere in Oxford? A question for future research…

More about Silking

- Kathpalia, YP. ‘Conservation and restoration of archive materials.’ UNESCO, 1973. [PDF]

- Krueger, H. ‘Silking’ section of ‘ The Core Collection of the Manuscript Division at the Library of Congress‘. Book & Paper Group Annual Vol. 14, 1995.

- ‘Preserving the Manuscript: Desilking “A Christmas Carol“‘, Thaw Conservation Center, The Morgan Library & Museum, 2011.

More about medieval musical liturgical manuscripts

- Hiley, D. Western Plainchant: A Handbook. OUP, 1995.

- Hughes, A. Medieval Manuscripts for Mass and Office: A Guide to Their Organization and Terminology. University of Toronto, 1995.

- Digital Image Archive of Medieval Music (DIAMM)

- Medieval Music Research Guide, Princeton University Library – lots of links to online image databases

- Sciacca, C. ‘Liturgical Manuscripts – an overview. ‘ British Library.

medieval manuscripts exhibition #mss2017

Change and Decay: a history of damage and conservation in Balliol’s medieval manuscripts

Balliol College Historic Collections Centre

St Cross Church, Manor Road, Oxford OX1 3UH

A new exhibition of medieval manuscripts will be in place for Oxford Open Doors (9-10 September 2017) and throughout Michaelmas Term (until 10 December).

Opening hours: Saturday 9 September and Sunday 10 September 12-4 pm both days for Oxford Open Doors, Saturday 16 September 2.30-6.30 pm for Balliol Society and Oxford Alumni Weekend, and tba. Individuals and groups are also welcome to visit at other times by appointment with the archivist – contact

Visiting hours are normally Mon-Fri 10-1 and 2-5; appointments aren’t meant to be exclusive, it’s just that the exhibition and reading room are in the same space and we need to plan ahead to ensure that visitors and researchers are here at different times.

Further information and related events will be advertised here.

The exhibition, curated by Balliol’s Archivist and Curator of Manuscripts, Anna Sander, includes more than 20 of Balliol’s 300+ original medieval manuscript codices and a number of contemporary documents from the college records, and highlights a decade of work on the archives and manuscripts by the team of professional conservators at the Oxford Conservation Consortium, of which Balliol has been a member since 2006.

Balliol’s 2014 condition survey of all manuscript books

2017 medieval mss catalogue print format [PDF, 9MB]

List of manuscripts on display

– with links to exhibition catalogue entries, more images and articles on related topics. Catalogue entries may not be identical in the blog posts and the print-ready PDF – the latter has been formatted to fit each manuscript’s entry on 2 sides of A4, i.e. a single opening, but there is no such restriction on blog post length.

Case 1. College Archives D.4.1 Statutes of Dervorguilla. 1282, in Latin, on parchment. First Statutes of Balliol College, with seal of Dervorguilla de Balliol. [exhibition entry] [related documents]

Case 2. College Archives Membership 1.1. First Latin Register of College Meeting Minutes 1514-1682, in Latin and English, on paper. Earliest surviving records of Balliol College’s Governing Body. [exhibition entry] [images online]

Case 3a. MS 349 15th century. Collection of nine texts related to the office of priesthood, in Latin, on parchment. Bequeathed to Balliol by Dr George Coningesby in 1768. Closed to show the only medieval binding in Balliol’s manuscript collection. [exhibition entry] [Mynors catalogue entry] [not yet digitized]

Case 3b. MS 350 12th, 13th & 14th centuries, 3 medieval treatises on English law, including Herefordshire section of Domesday. Victorian vellum binding, in Latin and Anglo-Norman French, on parchment. Bequeathed to Balliol by Dr George Coningesby. [exhibition entry] [Mynors catalogue entry] [images online]

Case 4. MS 263 14th-15th century. Texts on poetic and rhetorical composition, in Latin, on parchment. Rebound 1720s. Provenance unknown. [exhibition entry] [Mynors catalogue entry] [not yet digitized]

Case 5. MS 238E ca.1445. 5th volume of medieval encyclopedia, Fons Memorabilium Universi, compiled by Dominicus Bandini de Arecio, in Latin, on parchment. Conserved and rebound ?early 2000s. Copy commissioned and given to Balliol by William Gray, Bishop of Ely (d.1478). [exhibition entry] [Mynors catalogue entry] [images online]

Case 6. MS 148 2nd half 13th century. ‘Bernardi opuscula’, collection of short texts by 12th century Cistercian theologian and reformer Bernard, Abbot of Clairvaux, in Latin, on parchment. Rebound 1720s. Given to Balliol by William Gray, Bishop of Ely (d. 1478). [exhibition entry] [Mynors catalogue entry] [images online]

Case 7. MS 253 13th century. ‘Logica vetus’ and other texts by Aristotle, in Latin, on parchment. Rebound 1720s. Provenance unknown; late medieval Balliol ownership inscription. [exhibition entry] [Mynors catalogue entry] [images online]

Case 8. MS 12., aka Arch C 1 6. Ca. 1475. Josephus, Antiquitates Judaicae (History of the Jewish People), in Latin, on parchment. Printed at Lübeck by Lukas Brandis, ca. 1475. Rebacked/rebound several times, conserved 2010-11. Given to Balliol by William Gray, Bishop of Ely (d. 1478). [exhibition entry] [Mynors catalogue entry] [ISTC entry] [not yet digitized]

Case 9a. MS 367 11th century. Antidotarium – medical recipes and remedies, in Latin, on parchment. Victorian binding. Probably given to the College by Sir John Conroy, 1st Bt, Fellow of Balliol 1890. [exhibition entry] [Mynors catalogue entry] [images online]

Case 9b. MS 348 13th century. Vulgate Bible, in Latin, on very thin parchment. ‘Pocket Bible.’ Rebound 1720s.In Balliol by the 17th century; provenance unknown. [exhibition entry] [Mynors catalogue entry] [not yet digitized]

Case 9c. MS 451. 1480s. Book of Hours (Use of Rome), perhaps from Ghent or Bruges, in Latin on parchment. Early 19th century binding by by C. Kalthoeber of London. Given to Balliol by the Rev. EF Synge. [exhibition entry] [Mynors catalogue entry] [not yet fully digitized]

Case 9d. MS 378 Undated. Prayers to the Virgin Mary, in Ethiopic, on parchment. Original wooden boards without cover. From the personal library of the Rev. Benjamin Jowett, Master of Balliol 1870-1893, other provenance unknown. [exhibition entry] [Mynors catalogue entry] [images online]

Case 10. MS 396 Early 14th century. Five leaves of a noted Sarum Breviary, one of the liturgical books used for the Daily Office, in Latin, on parchment. These leaves were found and removed from the binding of an ‘old dilapidated’ College account book in 1898, by George Parker of the Bodleian Library. [exhibition entry] [Mynors catalogue entry] [images online]

Case 11. College Archives E.1. 1320s-1350s. Title deeds relating to property at Long Benton (Much/Mickle Benton) near Newcastle, given to Balliol College by Sir Philip Somerville, in Latin, on parchment, with seals. [exhibition entry] [images online]

Case 12. MS 116 Later 13th century. Commentary by Eustratius, an early 12th century bishop of Niceaea, on Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, in Latin, on parchment. Rebound 1720s. At Balliol by the late 14th century; provenance unknown. [exhibition entry] [Mynors catalogue entry] [images online]

Case 13. MS 277 Late 13th century. Aristotle’s Metaphysics, and Meteorology, trans. Moerbeke, and Ethics, trans. Grosseteste, in Latin, on parchment. Rebound 1720s. May have been at Balliol in the 14th century, alienated and returned in the 15th; given by Mr Robert Rok (Rook). [exhibition entry] [Mynors catalogue entry] [images online]

Case 14. MS 384 15th century. English Book of Hours according to the Use of Sarum, in Latin, on parchment. 18th century binding. At Balliol since the 18th century; provenance unknown. [exhibition entry] [Mynors catalogue entry] [some images online]

Case 15. MS 210 1st half 13th century. Several texts by C12-13 University theologians, in Latin, on parchment. Rebound 1720s. Given to the College by Roger Whelpdale, sometime Fellow of Balliol and Bishop of Carlisle in 1419-20 (d. 1423). [exhibition entry] [Mynors catalogue entry] [images online]

Case 16. MS 173A 12th and 13th century. Two collections of short texts bound together, on medieval music theory, in Latin, on parchment. Rebound 1720s. Given to Balliol by William Gray, Bishop of Ely (d. 1478). [exhibition entry] [Mynors catalogue entry] [images online]

Case 17. College Archives B.22.1. Ca. 1200, charter re St Lawrence Jewry, London. (Jewry?) Parchment, 2 pendent seals. Balliol’s oldest document, predates Balliol’s association with the property. Rehoused by OCC, 2007. [exhibition entry] [images online]

Case 18. MS 354 Early 16th century. Commonplace book of London grocer Richard Hill, in English, Latin and French, on paper. Medieval song or carol texts, literary extracts, poems, religious and spiritual texts, notes on farming and trade, recipes, proverbs, etc. Original limp parchment cover. Provenance unknown. [exhibition entry] [Mynors catalogue entry] [images online]

Case 19. MS 240 12th and 14th centuries. Miscellany of religious texts, in Latin, on parchment. Conserved and rebound by Andrew Honey, 1990s. From the priory of Monks Kirby (Warwickshire). Given to the College by Richard Bole, Archdeacon of Ely (d.1477). [exhibition entry] [Mynors catalogue entry] [images online]

Find out more

- Flickr collection for the exhibition – not all the mss have been photographed in full yet, so this collection will grow.

- Notes on light by Anna Sander

- Tiny books, tiny writing by Sian Witherden and Anna Sander

- Manuscript fragments in early printed books project

- Fragment Fridays by Annaliese Griffiss

- A description of Balliol Arch.C.1.9 by Sian Witherden

- Vandalism

- Further reading – online and print resources

boxes

Pre-before: Last week came the final batch of new boxes for Balliol’s medieval manuscripts! or mostly medieval. And mostly codices. The mss were measured up by OCC and made by the Bodleian’s PADS department – we all use them a lot and their services are quick, reasonable and brilliant. They’ve worked out a good system with the conservators, who can also make boxes when necessary, but use PADS for anything that’s custom-measured but without special requirements.

Before: The assembled mss, most of which have had no packaging before at all. A few are being replaced, as their old boxes are not acid-free and/or don’t fit well, are wearing out, don’t provide adequate support or compression or padding, and so on. Some of the volumes still require conservation treatment, but it won’t change their dimensions in ways that will require a different box, so we can proceed with boxing now.

This boxing campaign, which was interrupted for quite a while due to conservation planning hitches at our end, is now complete in the sense that there are no longer ANY unboxed manuscripts on the shelves! Boxes are the first defense against climatic fluctuations and all kinds of damage. There are still boxes and heavy four-flap folders that don’t fit well or could do with changing for other reasons. We have some beautifully made drop-spine solander boxes with wool felt linings, which is not great for our high-friction decaying half-calf bindings and is attractive to pests. So we’ll be looking at changing or modifying those in due course. But the first stage of ‘a box for every book’ is complete, a satisfying milestone in the many useful outcomes of our 2014 condition survey of the manuscripts.